[ad_1]

Milton Friedman once warned that nothing is so permanent as a temporary government programme. The aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic will be a test of whether he was right. With millions of people unable to work last year because of lockdowns, governments around the world implemented temporary programmes to support their citizens’ incomes. How and to what extent policymakers undo this support will determine the shape of the post-pandemic welfare state.

The UK faces one crunch moment at the end of September, when the government plans to reverse a £20-a-week crisis-era uplift to benefit payments. Last week, Boris Johnson told MPs this decision was in everyone’s best interests. “The best way forward is to get people into higher wage, higher skilled jobs, and if you ask me to make a choice between more welfare or better, higher paid jobs, I’m going to go for better, higher paid jobs,†the prime minister said.

But no one had asked him to make a choice between more welfare or better jobs. Indeed, it’s not clear this is a real trade-off at all.

For a start, universal credit is a benefit for the working poor and those who can’t work, as well as for jobseekers. Of the roughly 6m people who receive universal credit, 36 per cent are working and a further 20 per cent have “no requirements to workâ€, for example, because they are too ill or they have a baby under the age of one.

What of those who are physically able to work but are currently unemployed? It seems clear in theory that a £20-a-week cut to their incomes would increase their incentive to find a job. But it is worth remembering that work incentives in the UK are already strong because benefit levels are so low.

Even with the £20 boost, the current basic benefit for a single adult over the age of 25 is less than £100 a week — half the UK’s minimum income standard (an estimated budget deemed adequate to meet material needs and participate in society) and well below the government’s own measure of absolute poverty, according to the Resolution Foundation think-tank.

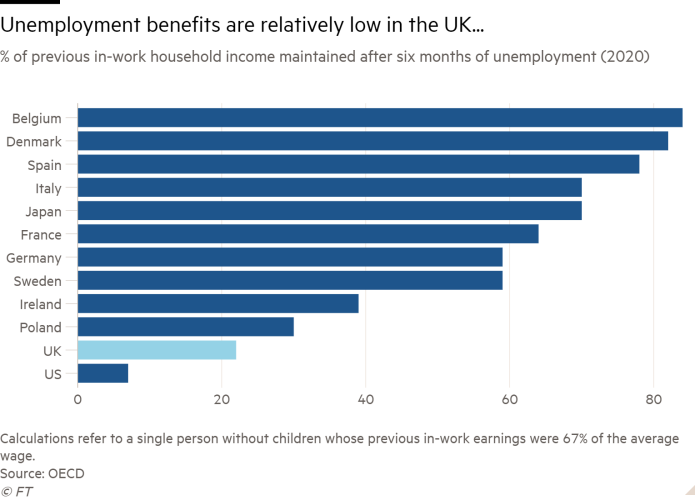

As a percentage of the jobseeker’s previous income, the UK has some of the lowest unemployment benefits in the OECD. The financial incentive to find a job, while slightly weaker if the £20 per week were made permanent, would still be strong by international standards.

The real world evidence that benefit cuts boost employment is also thin. A working paper by economist Arindrajit Dube found there was “surprisingly little overall effect on employment†in different US states in July 2020 when a generous boost to US unemployment benefits expired. Similarly, there is not much sign yet this year of higher job-seeking activity in US states that have ended federal pandemic-era unemployment benefits early.

This suggests there are other barriers or disincentives to people finding work, such as the location of available jobs, the availability of local transport, the hours and shift patterns on offer and the cost of childcare. The UK, for example, has some of the highest childcare costs in the OECD.

The best argument to cut the £20 a week is one Johnson did not make, which is simply that it would be expensive to keep it. The Institute for Fiscal Studies calculates it would cost £6.6bn a year to make the increase permanent, adding about 10 per cent to the annual cost of universal credit (albeit undoing only a fraction of the total benefit cuts implemented since 2010.) Ministers want to maintain some fiscal discipline and have other spending priorities for the post-Covid economy. These include some measures to help the unemployed and low-paid, such as more vocational training.

Against that, I would argue that returning to benefit levels that were, for many, set well below the poverty line would hurt not only those affected but the prospects for their children and their local economies. When ministers increased the generosity of the safety net last year, it was an implicit acknowledgment that it was too threadbare to get us through the crisis. “We will . . . act to protect you if the worst happens,†Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, said when he announced the uplift in March last year. But people have their own crises all the time. Their employers go bust; they have accidents; they become sick.

This is the terrain on which the argument should take place. Johnson’s claim about boosting jobs distracts from the real question: what should a safety net look like for the 21st-century economy, and how much are we prepared to pay for it?

[ad_2]

Source link