[ad_1]

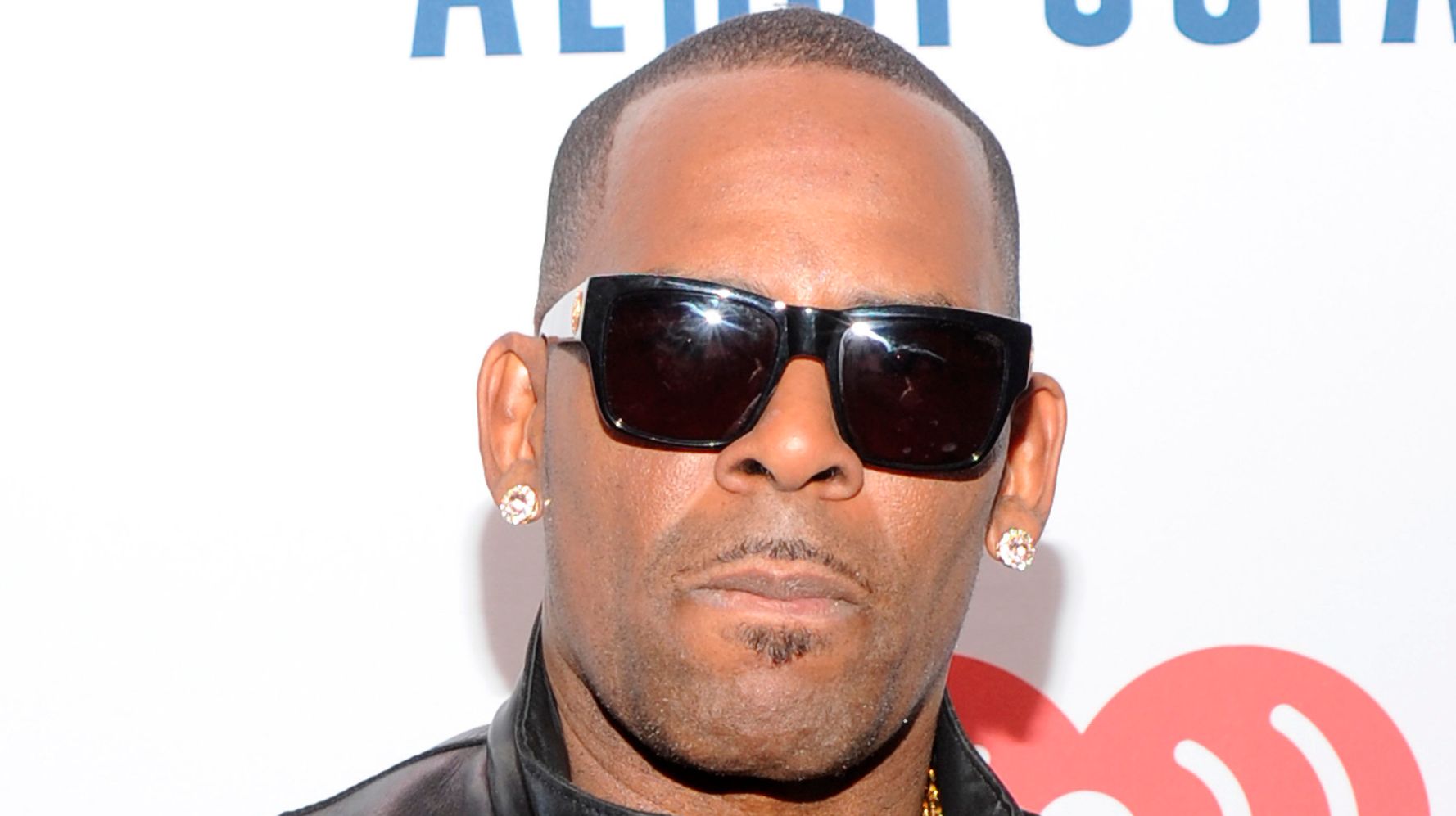

After the premiere of “Surviving R. Kelly,†there has been considerable outrage about pedophilia and sexual assault and physical abuse of minors in the music industry and in society at large. Yet the response to the adult women who accused Kelly of sexual, physical and psychological violence has been far less sympathetic and compassionate.

To many in the viewing public, the black women alleging abuse by Kelly are victims — but with an asterisk. These women must be either making bad decisions or chasing celebrity or fame. However, this type of framing illustrates society’s lack of knowledge about what constitutes abuse and how anyone becomes a victim in a cycle of abuse.

According to a report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, “The Status of Black Women in the United States,†more than 40 percent of black women will experience physical violence from an intimate partner during their lifetime. The report also details that black women “experience significantly higher rates of psychological abuse — including humiliation, insults, name-calling and coercive control†than nonblack women.

‘Surviving R. Kelly’ is a reminder that, while it may not be as publicized in the news, many black women will find themselves in similar situations of abuse and coercion.

Black women are particularly vulnerable to entering and remaining in cycles of abuse for a number of reasons. Studies indicate that financial insecurity is a significant factor, as reported intimate partner violence is more prevalent among those living with financial insecurity. The unemployment rate for blacks is nearly double the rate for whites.

Beyond income levels, some black women survivors internalize the strong-black-woman stereotype, which dictates that black women can and must endure through any circumstance without complaining or showing signs of weakness.

According to mental health social worker and writer Feminista Jones, black women are “more likely to rely on religious guidance and faith-based practices when working through relationship issues.†African-American-centered religious and faith-based approaches to abusive relationships often encourage forgiveness, which does not always come with accountability and transformative or restorative processes aimed at breaking abusive cycles.

Black women also contend with reasonable suspicion or outright distrust of the criminal justice system. From discriminatory treatment throughout the process of reporting to the fear of being seen as a race traitor for publicly accusing a black man of harm, black women often and understandably steer clear of engaging law enforcement.

It is even more difficult for black women to deal with all these barriers to escape when what they’re experience is more coercive than abusive. The Department of Health and Human Services defines sexual coercion as “unwanted sexual activity that happens when you are pressured, tricked, threatened or forced in a non-physical way.†Many of the women and girls in “Surviving R. Kelly†were allegedly coerced under promises of a career or perhaps felt compelled because Kelly is a celebrity.

For black women in relationships with noncelebrity men, promises of safety from other abusive dynamics or of financial stability and security can establish a dynamic built on a sense of indebtedness and guilt. A growing sense of obligation emerges over time, and eventually leaving doesn’t seem like a viable option.

Coercion can lead to abusive dynamics. While an initial “yes†is not consent in perpetuity, many women eventually come to feel it’s too late to say “no.†Women in the docu-series detail physical assaults, food deprivation, being required to notify Kelly if they needed to use the bathroom, compulsory participation in sex acts and being isolated from other people. These tactics mirror those experienced by thousands of women every year in coercive and abusive relationships. Victims of coercion and abuse report being separated from loved ones, promises of rewards for sex, threats against their family members and even threats on their lives.

Still, the question remains: Why don’t women ― especially adult women ― in abusive relationships just leave? Well, it’s not always easy or safe to simply walk away. It’s not uncommon for abuse victims to identify with and protect their abusers. Clinical psychologists featured in “Surviving R. Kelly†spoke about how predators choose their victims, the processes in which a victim begins to identify with and defend her abuser and the numerous challenges that victims face when they attempt to leave.

The question remains: Why don’t women in abusive relationships just leave? Well, it’s not always easy or safe to simply walk away.

One of the most alarming facts presented in the docu-series is that on average, a woman will leave an abusive relationship seven to 10 times before she permanently leaves. And when she leaves, she is often actually in more danger. More than half of intimate partner homicides involving female victims occur after she ends the relationship. The fear that abused women feel is real and must be considered when people wonder, “Why don’t they just leave?â€

Their lives could be in grave danger if they do. Alarmingly, domestic violence homicides are among the leading causes of death for black girls and women ages 15 to 35. Black women are three times as likely as white women to die because of domestic violence. Too often, leaving marks them for death.Â

Consequently, the behavior of Kelly’s alleged victims isn’t surprising, as it mirrors what experts know about abusive and coercive intimate relationships. The documentary contextualizes the stories of Kelly’s accusers and challenges his defenders to better understand the complicated dynamics of abuse for all women and specifically black women.

The adults accusing Kelly of abuse deserve our attention and our unequivocal support. When we deny support to victims of abuse because we believe they should have behaved differently, we venture into dangerous victim-blaming territory. Fear of victim blaming keeps many women (and men) from coming forward with their experiences. The risk of not being believed or being blamed silences victims, particularly black women and girls.

Although some of Kelly’s accusers from the alleged cult lived to tell their stories, they survived what many women in abusive and coercive relationships do not. While it is challenging for even those attempting to sympathize with his alleged victims to defend the actions of seemingly consenting adults, comprehending how abusers operate, who they target and how they maintain power is integral to holding Kelly accountable for his allegedly ongoing abusive behavior.

“Surviving R. Kelly†is a reminder that, while it may not be as publicized in the news, many black women will find themselves in similar situations of abuse and coercion. These women deserve better from us.

Treva B. Lindsey is a professor of women’s studies at Ohio State University and the author of Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington, D.C. Follow her on Twitter @divafeminist.Â

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link