[ad_1]

The Group of Seven industrialized democracies – the US, the UK, Japan, Germany, Italy, France and Canada – have regained saliency in light of the rapidly changing geopolitical and global security environment, especially as countries look to plan for economic recovery in a new global order.

Established in 1975, the G7 over the years has borne criticism for being “outdated†by not including emerging economic powers as members. Moreover, a rise in the stature of the Group of Twenty – which includes such states as India, South Africa, Brazil and more in a forum led by finance ministers and central banks – has thereby accentuated the missing presence of such states in the G7.

Discussions pertaining to potential expansion of the grouping – with former US president Donald Trump calling for the inclusion of India, Australia, Russia and South Korea within the format in 2020 – have gained prominence. Trump’s invitation, however, remained abstract at best, with little clarity over whether such an expansion would be permanent or whether the other G7 members would acquiesce to it.

Now, with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson looking to formalize this expansion in his capacity as president of the G7 for 2021, the debate has re-emerged. What is of particular note is Japan’s strong pushback against the inclusion of India, Australia and South Korea (as Johnson’s invitation does not extend to Russia), particularly considering the close ties Tokyo shares with India and Australia in the Indo-Pacific region.

Considering the “Special Strategic and Global Partnership†and naturally synergic relationship between Japan and India, underpinned by a “deep, broad-based and action-oriented†approach toward the peace and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific region, such a stance by Tokyo is unexpected.

More so, as Japan campaigns for permanent membership for the Group of Four – India, Japan, Brazil and Germany – in the United Nations Security Council and has actively sought India’s inclusion in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), such an overture by Japan seems like deviation from its warm outlook toward India.

Concurrently, keeping in mind Japan’s consideration of Australia as a “semi-ally,†defined by the “special strategic partnership†between the two countries and the shared commitment toward freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law, Japan’s non-supportive stance for the expansion of the G7 – that too by inclusion of its own allies and friends – seems peculiar.

However, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s opposition is likely drawn on several concerns.

According to reported official statements, Japan is unwilling to “institutionalize†the G7 and dilute its framework after a turbulent and “dysfunctional†2020. Instead, Tokyo wishes to maintain the forum’s existing framework and limit the privilege of membership to states advocating similar core values.

In particular, considering Japan’s unsteady and historically tense and fractious ties with South Korea, Tokyo’s refusal is likely also based on Seoul’s proposed inclusion in the framework. At the same time, Japan’s decision is based on its dualist approach to global and regional frameworks, by which it seeks to maintain its national strategic interests and possibly its global leadership image.

One of Tokyo’s foremost concerns is based on geopolitics and its heightening tensions with China. Despite its massive economic prowess, China has remained absent from the discourse on the G7’s expansion.

The potential inclusion of India, Australia and South Korea has by all evidence irked Beijing, with state-sponsored media outlets calling the move “more symbolic than substantive,†warning India not to “[play] with fire†and treat China as an “imaginary enemy,†while urging the G7 leaders to prioritize economic recovery over geopolitics and anti-China sentiments.

Amid such a response, Japan – as well as other G7 powers such as Canada, France and Germany – is likely cautious of the potential backlash from Beijing in the region.

Britain’s overture to expand the G7 is being viewed at present as an attempt to move gradually toward its proposed “D10†grouping, a coalition of 10 democracies. Ideated mainly as an initiative driven by 5G (fifth-generation telecommunications) connectivity infrastructure, the proposed coalition received strategic coverage amid a “moribund†G7 summit in 2020.

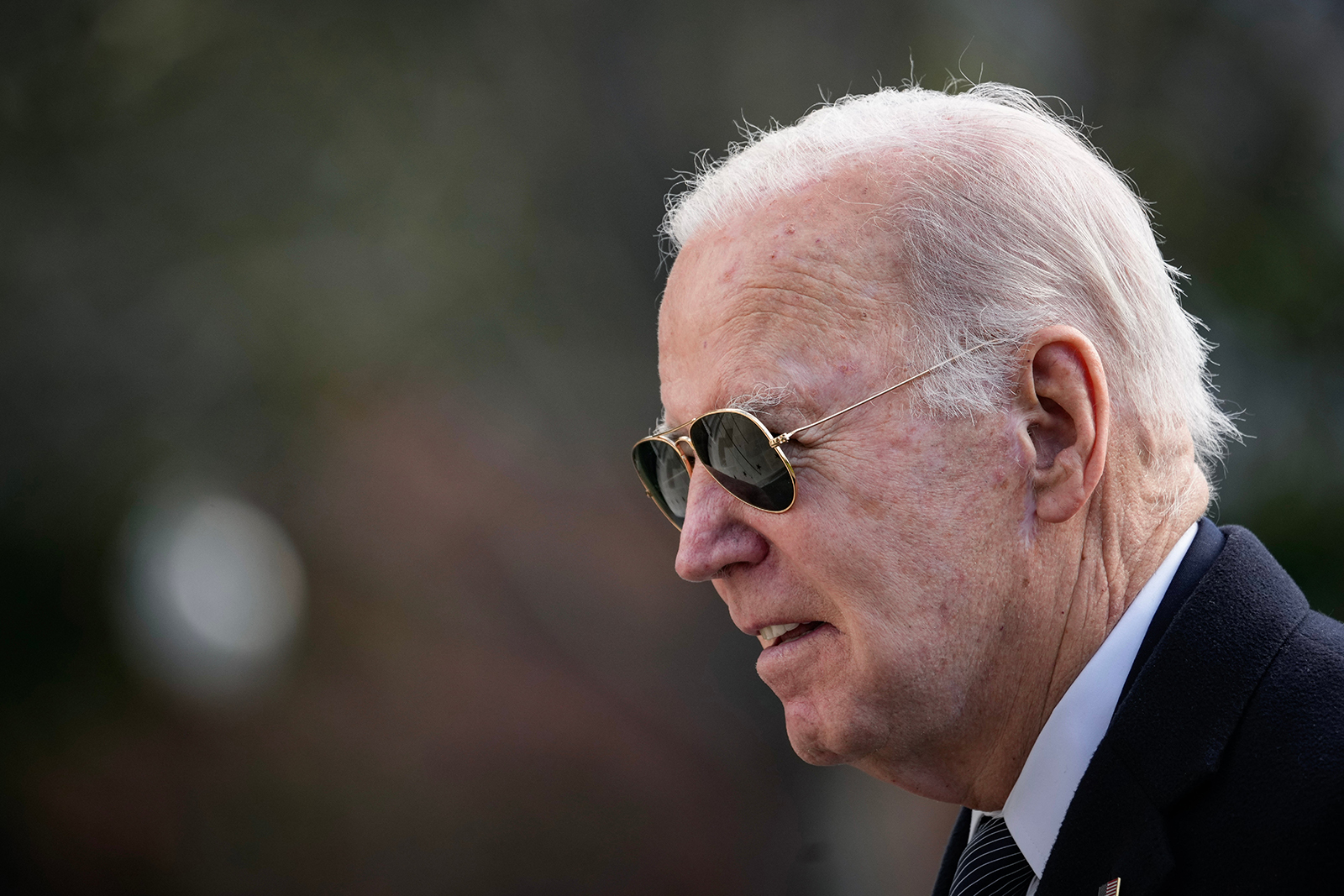

Although newly elected US President Joe Biden’s stand on an expanded G7 has not been made clear, his hopes to convene an international “summit of democracies†could find synergy with Britain’s D10 ambitions.

However, an expanded G7 taking the shape of D10 – or G10 – the 5G-driven focus of the ideated coalition would change, taking on a grander strategic intent vis-à -vis China.

Considering the present security climate, and the fact that Japan is facing an increasingly belligerent China directly in its neighborhood, it is unwilling to escalate tensions by creating an overtly anti-China coalition. Therefore, Japan is not keen on endorsing the creation of a G10 as a “rival alliance†to China – especially as a back-channel structure created by the UK.

Moreover, without the stewardship and political ingenuity with which former prime minister Shinzo Abe led Japan, and in light of the political pressure Suga faces prior to the Japanese general elections this year, Tokyo is displaying indecisiveness on several issues. Confronted with pressure from divided political groups vis-à -vis China, leadership has become a critical factor in determining Tokyo’s foreign outlook and creating consensus on how far Japanese foreign policy can be anti-China.

Japan has long championed economic multilateralism via various frameworks, such as the Asian Development Bank, exhibiting leadership in taking forward the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership after the US withdrawal from the TPP (earlier form of the CPTPP) under Trump, and by being one of the key proponents for the first pan-regional inter-governmental frameworks in the realms of economy and security – the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

Yet despite being a proactive supporter of economic and liberal multilateralism, Japan has had a conservative outlook when it comes to multilateral expansionism. Japan has been a member of the G7 since its first summit meeting in 1975; being the sole Asian state in a grouping of such highly industrialized economies sharing values of democracy has been a jeweled accomplishment in Tokyo’s multilateral outreach.

Hence, the G7 falls under Japan’s global ambitions and largely drives its multilateral connect with Western counterparts. It has allowed Japan to imbibe a leadership role – as seen with Abe’s call to take the lead in 2020 on a G7 statement on Hong Kong – especially as Tokyo represents the sole Asian voice in the grouping.

Japan’s desire to remain the only Asian power in the grouping and sustain robust relations with the US without any impediments – thereby limiting the extension of G7 membership status to India, Australia and South Korea – remain important factors guiding Japan’s disapproval of an expanded G7.

Japan’s focus is hence going to be on a continuation of the present G7 structure – in a bid to maintain its own strategic global presence –while engaging deeply with Indo-Pacific counterparts in bilateral and other multilateral forums.

Bilaterally, while sharing strategic complementarity on major Indo-Pacific security, economic and connectivity facets, Japan and India also have their fair share of disagreements, ranging from data protection to the question of inclusivity in the region.

For instance, differences on data-protection policies have figured heavily in India-Japan ties – Tokyo supports free flow of cross-border data, while the same puts pressure on a non-aligned New Delhi to share confidential data with foreign powers, thereby inculcating it in a discussion-demand technology paradigm.

Further, India-Japan ties – which acquired not only strengthened economic, strategic and defense partnerships under the previous Japanese leadership but also witnessed a personalistic bond between Abe and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi – have not retained the same momentum in the post-Abe period, no matter how India-friendly Prime Minister Suga may appear to be.

While the foreign and defense policies under Suga may largely stay the same, the current government’s approach toward India is moderate. The missing personal camaraderie between Japan’s Suga and India’s Modi – as well as other global leaders – drives the present Japanese government’s decisions; the Abe-led personal touch in diplomatic outreach is missing in Tokyo’s present leadership.

Debate continues over the relevance of the G7 as a multilateral and effective forum that influences the global governance narrative.

The UK, under the Johnson government, seems to have a renewed outlook toward the G7 and aims to connect this outlook with its new approach toward the Indo-Pacific region. Johnson’s hint that the involvement of these will be “deeper†this year, coupled with reports that London has encouraged the six other G7 states to sign a joint charter – named the “Open Societies Charter†– with the three guest states to integrate their inclusion in the G7 further this narrative.

As G7 president and host, the extent to which the UK can convince Japan on an expanded G7 grouping is to be seen; although Japan’s reluctance might discourage the UK from exhibiting an active campaign for an expansion. Yet Tokyo under Suga should not be shortsighted and must adopt the “global character†for its post-pandemic diplomacy that Shinzo Abe always invested in.

More important, Japan cannot afford to miss sharing the table with India, its “special†and “global†partner, at a time when New Delhi’s foreign policy is itself imbibing anti-China seeds. As leading Asian partner states, global politics needs a new mode of interaction with the lead of Japan and India in the post-pandemic political and economic order.

[ad_2]