[ad_1]

The writer is the author most recently of ‘The Hidden History of Burma: Race, Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy in the 21st century’

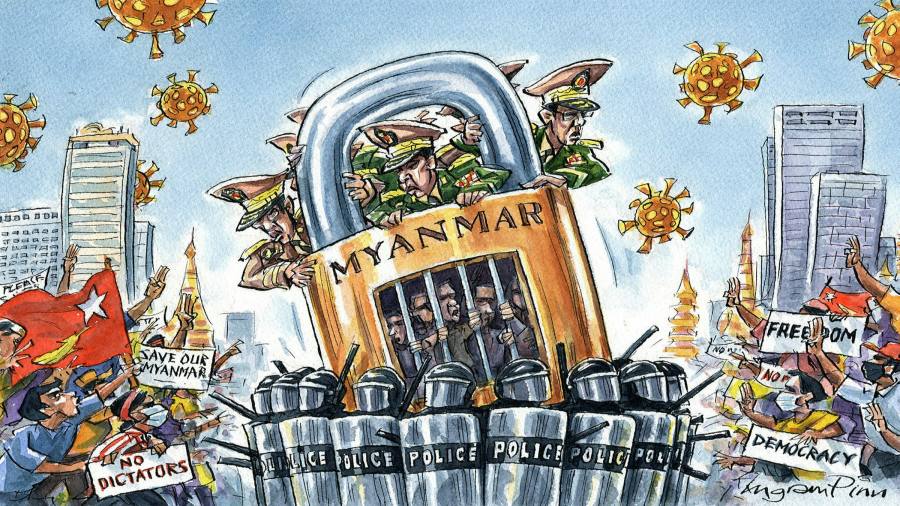

The Myanmar coup was meant to be a surgical reset: a rebalancing of power back from Aung San Suu Kyi after her decisive win in November’s elections. Instead, the generals may have inadvertently set off a new revolutionary dynamic at a time of intense social and economic upheaval. The country’s future is now up for grabs.

Eleven years ago, the generals in charge at the time abolished their junta and ushered in a new constitutional set-up, one in which the army would share power with an elected president and parliament. They had overthrown an army-backed socialist regime in 1988 and grown a new market economy to their advantage. They thought the new political system would secure army dominance, protect their wealth and gain a degree of popular support. The old generals then stepped down. Following a period of unprecedented political liberalisation, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy contested and won elections in 2015.

Five years of edgy cohabitation followed, between Aung San Suu Kyi and Min Aung Hlaing, the new army commander-in-chief. Though the army kept a firm grip on security, Aung San Suu Kyi ran all other aspects of government, including a $25bn a year budget and foreign relations. She grew in power and popularity. And she set as her prime goal amendments to the constitution that would bring the army under her authority.

The commander-in-chief hoped November’s elections would lead to some attenuation of her power, perhaps a shot at the presidency for himself. Instead, the NLD won a landslide victory. Then came allegations of voter fraud, army demands by the army these be investigated, rejection of these demands by the NLD — and then the coup. That wasn’t inevitable. What was inevitable was a drive to weaken Aung San Suu Kyi and ensure a second term didn’t lead to constitutional change.Â

The army’s intent is to reset the clock to 2010 and run the story again — this time with Aung San Suu Kyi permanently sidelined. She is under house arrest. The commander-in-chief has promised fresh elections within a year, but it’s hard to imagine these will include the NLD. The detentions over the past two weeks suggest the army is trying to build a case against the party, combining existing allegations of electoral fraud with broader conspiracies involving corruption and foreign collusion. The commander-in-chief may not want a return to the brutal days of kleptocratic junta rule. But in his quest for a new political landscape, he miscalculated one thing: ordinary people’s burning desire to be rid of military domination once and for all.Â

Hundreds of thousands of people have now taken to the streets, calling for an end of army rule. Thousands of civil servants and public sector workers have also left their jobs, paralysing government. Leading the resistance is a new generation of activists.

These protests are unlikely to topple the military administration. Mediation leading to compromise between the commander-in-chief and Aung San Suu Kyi is almost as improbable. There’s nothing in Myanmar’s modern history that suggests senior officers will break rank. And compromise is almost a dirty word in Myanmar political culture.Â

More likely is a spiral of protest and repression that makes consolidation of military authority impossible. The country may become ungovernable. Politics will then come up against Myanmar’s other realities: racial and religious discrimination, ethnic-based armed conflict, extreme poverty, soaring inequality and climate change. There are a million Rohingya and other refugees. Dozens of non-state armies and hundreds of militias hold sway across the borderlands. At the apex of Myanmar’s political economy is not the army but transnational moneymaking networks more powerful than any institution. Millions have lost their land and migrated within the country or to Thailand. Tens of millions more lead the most precarious of lives: a recent study suggests those making less than $1.90 a day have more than tripled to 63 per cent of the population since the pandemic began. At the same time, a decade ago almost no one had a phone; now virtually everyone is on Facebook.

Myanmar is not on the verge of democracy. But it’s on the verge of revolutionary change. The pact that’s collapsed between the army and Aung San Suu Kyi was essentially a conservative one, barely holding together this country of 54m. It’s impossible though to say in which direction this change will go.

What’s hobbled Myanmar politics all these years has been gerontocracy and a narrow focus on elections and constitutions. Today’s protest organisers have shown huge courage and determination. They are of a new and more confident generation, more tech-savvy and more connected to the wider world. But to succeed they will need to craft a progressive agenda across ethnic lines, centred on inequality and development as well as peace and justice. They will need to reshape society as well as restructure the state. Myanmar’s young people have inherited terrible legacies. They should reject them. The future is now rightly in their hands.

[ad_2]

Source link