[ad_1]

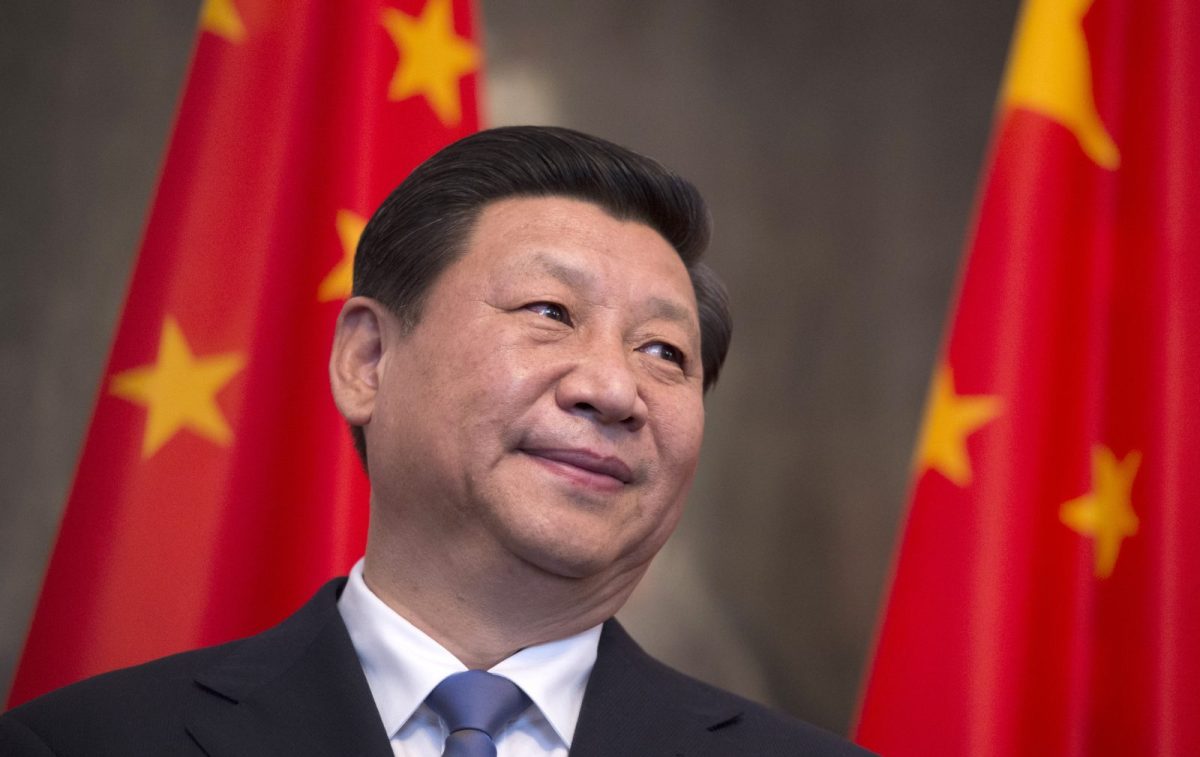

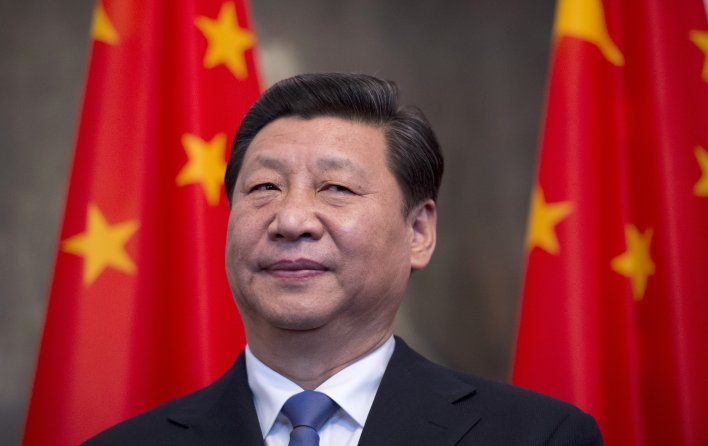

On January 9, Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted the ninth Summit of CEE Leaders with China, which had been scheduled to take place in April last year but had to be postponed because of the devastating impact of the Covid-19 pandemic sweeping the globe.

Eventually taking place over videoconference, the event aimed at providing the best possible platform in the given circumstances for boosting cooperation between Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, North Macedonia and Greece on the one hand and China on the other – now commonly known as the “17+1†group.

The arrangement was commenced in Warsaw in 2012, and originally had a “16+1†format (with Greece joining later on). It serves as a platform for economic, cultural and political cooperation between the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (including some Baltic states) and China in order to find common ground to utilize the Middle Kingdom’s rise in the best possible way for the region, and undoubtedly for Beijing as well.

What is significant about this year’s e-meeting is the fact that President Xi himself reached out to the leaders of the group to prove their importance after his country agreed on the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) in December 2020, which not all group members are part of.

Along with Polish President Andrzej Duda, the meeting was attended by many influential leaders including Czech President Miloš Zeman. However, countries such as Bulgaria, Estonia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Romania were “only†represented by government ministers, instead heads of state – a move some commentators considered a “diplomatic slap†vis-à -vis Beijing, or more accurately Xi Jinping himself.

The decision made by the mentioned “dissenters†was announced on February 7 by Hospodářské Noviny, a daily newspaper in Prague, and neatly explained in Politico in a run-up to the summit on the February 5 as a geopolitical rationale associated with US President Joe Biden’s call to “form democratic alliances that will help counterbalance Beijing.â€

“The Baltic states are more sensitive than most of the EU about the need for close security relations with Washington and NATO because of their concerns about the threat posed by Russia,†we read in the article, which was then supported by a Twitter commentary from Michael Carpenter, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, who described the “17+1â€Â summit “as a litmus test of where Central Europeans stand on Beijing’s predatory infrastructure acquisitions and debt-trap diplomacy.â€

Without paying too much attention to the unfounded remarks made by Carpenter, it is important to note that they were scientifically debunked by both Deborah Brautigam, Bernard L Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, and Meg Rithmire, F Warren MacFarlan Associate Professor at Harvard Business School. Their recent article in The Atlantic tellingly titled ‘The Chinese ‘debt trap’ is a myth†did just that.

What is worth mentioning, however, is that Lithuanian Transport and Communications Minister Marius Skuodis clearly stated at the summit that his country sees “huge potential†for cooperation with Beijing, and others followed the same supportive tone.

Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, whose country puts strong emphasis “on infrastructure, science and innovation, as well as tourism, mobility, and SMEs,†said the “17+1†format builds bridges “complementing our efforts within the EU.â€

Serbian President Aleksandar VuÄić, whose country was disappointingly named and shamed in a recent report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) as a “Chinese client state,†described his country’s relationship with Beijing as “exceptional.â€

“Dialogue at the highest level is crucial for the further development of relations between China and Serbia in all areas, especially the economy, culture, and health care,†continued President VuÄić, adding that a visit by Xi to Belgrade was already confirmed. Furthermore, it is also worth mentioning that Serbia was the first European country to receive a million doses of Chinese Sinopharm’s Covid-19 vaccine last month.

President Milo Äukanović, who represented Montenegro at the summit, stated that it “is a small step towards creating something big, which will be witnessed by future generations.â€

With Hungary and China having signed a declaration of intent to cooperate on setting up a Fudan University campus in Budapest, and the country expecting to receive the first delivery of Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccine this week, Äukanović’s wish may well come true.

We already know that it was the foreign minister of Hungary, Peter Szijjarto, who famously said that “we, in this region, have looked at China’s leading role in the new world order as an opportunity rather than a threat,†when welcoming Chinese Premier Li Keqiang on his arrival for a “16+1†summit in Budapest in November 2017.

Chinese trade with the group reached US$100 billion for the first time in 2020 and the country is intending “to import, in the coming five years, more than $170 billion of goods from CEE countries … and raise two-way agricultural trade by 50% over the next five years,†as we heard from Xi during the summit.

Moreover, bearing in mind the vaccine shortages in the European Union, the Chinese president said “China will continue to provide vaccines to countries in need to the best of its capability, and do what it can to make vaccines a global public good and promote their equitable distribution and application around the world.â€

Another significant point raised by Xi at the summit relates to the need to improve connectivity by pursuing “high-quality Belt and Road cooperation,†“speeding up such major projects as the Budapest-Belgrade Railway,†and “supporting the development of the China-Europe Railway Express.â€

As far as “green consensus†is concerned, Xi urged participants to “advance international cooperation on climate change,†and proposed “setting up a China-CEEC STI Research Center and holding a China-CEEC Forum for Young S&T Talents†– the latter creating a unique opportunity for the youth from both sides of Eurasia to learn more about their distinctive cultures by enriching diversity and better understanding in the rapidly evolving globalized world.

Sadly, not everyone sees this as a favorable development, as many voices in the West are pushing for deterioration in the CEE-China relationship by labeling the “17+1†format as an instrument “being used to divide the European Union.â€

As a person who is very familiar with the political economy of the region and underlying international relations, and having had the privilege of participating in Professor John Mearsheimer’s lecture given at the Jagiellonian University in December 2015, I understand that our “economic intercourse with China makes them angry,†but as this famous realist explained, “Europe is not threatened by China.â€

Quite the contrary, as Professor Grzegorz Kołodko argues in his book China and the Future of Globalization: The Political Economy of China’s Rise:

“If China, understandably guided by its strategic interests, will contribute, if only slightly, to improving and developing the floundering quality of the transport, transit and transshipment [of] infrastructure in the Eastern European economies, this will be conducive rather than harmful to deepening and broadening European integration.â€

With the number of voices increasingly becoming displeased with the fact that some of us do not wish to act to our own socio-economic detriment by picking sides in the “extreme competition†between Washington and Beijing, it is a worthwhile reminder that embracing a “very zero-sum set of policies is not going to work,†as the director of the East Asia Program at Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, Michael D Swaine, accurately noted in my interview with him last year.

“I think there is definitely a very strong role for other countries to play. They have a major role in encouraging both the US and China to resist demonizing and to work from facts. US allies need to speak up more on this issue. They need to resist American pressure to dictate how they should respond to China,†Swaine said.

With the points mentioned above, as well as the fact that China can indeed save Europe from the influx of tens of millions of immigrants from Africa and the Middle East by investing in those regions (as is argued by both Grzegorz Kołodko and Kishore Mahbubani) – a topic that has proved to be very divisive – it would be better if we abandon this narrative.

Besides, as Kołodko argued in the book referenced above, “first and foremost, though, one has to do the math, as this is not a matter of sentiment; an economic calculation is what counts here.†To think otherwise, unfortunately, may prove to be detrimental to US interests in the region in the long run.

[ad_2]