[ad_1]

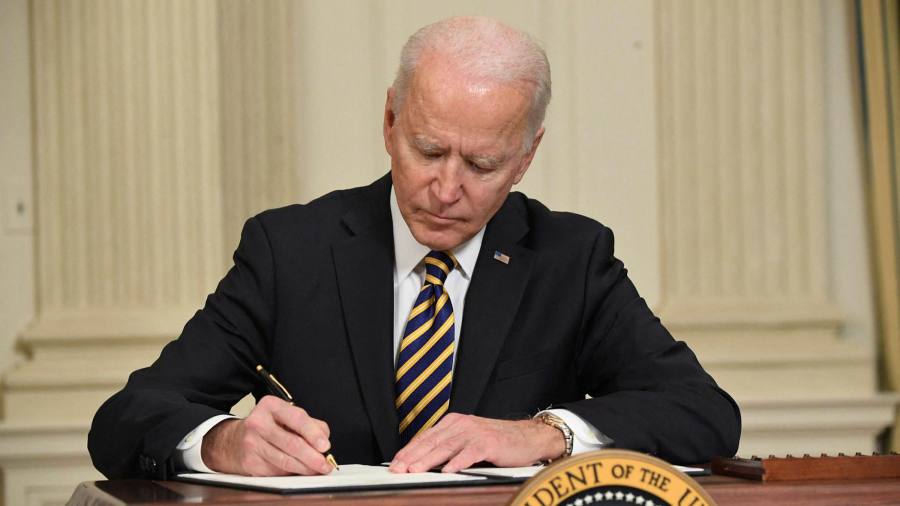

In all likelihood, US president Joe Biden will sign $1.9tn of fiscal relief into law this week, and himself into the annals. The American Rescue Plan is almost as historic as the pandemic it seeks to mitigate.

Consider, first of all, its raw scale. Barack Obama spent far less on the stimulus he passed during the financial crash of 2008-09. And that intervention was a one-off. The Biden bill is just the latest in a series of splurges over the past 12 months by the federal government. In buoyant financial markets, in an economy that has declined less than most, the effect is felt. The US has lessons to impart, though it also has fewer borrowing constraints than most nations.

If the bill’s price tag is eye-catching, the contents are tellingly Democratic. Much of the money goes to the unemployed and families with children. There is also much more in the way of subsidies for healthcare. To be clear, the relief efforts under Donald Trump were hardly Scrooge-like: the jobless were among the vulnerable groups helped, including via executive order when Congress stalled last summer. That redistributive bias has been taken much further by his successor. The change of president is having material consequences, not just ethical ones.

Yet a third reason to mark this bill as an event is its astronomical popularity. Unlike the New Deal, and despite Republican opposition in Congress, it is not remotely contentious among voters. Unlike the Obama stimulus, it has not set off an instant folk revolt to compare with the Tea Party. Even lots of right-leaning Americans support both the overall bill and lots of its provisions.

This public clamour for state intervention complicates all notions of the US as a free-market, anti-government culture. In attitudes to Obamacare, to inequality, a social democratic trend has been observable there for years. Even those who deplore the shift (and no one should feel relaxed about spending on the scale of this bill) must accept it as political reality.

Of course, relief should not be mistaken for permanent change. Most of the extra cash, in direct cheques, tax credits and unemployment benefits, are time-limited. Of the lasting reforms that Democrats had planned, the boldest, a $15 an hour federal minimum wage, has not made it through the Congressional sieve. Talk of the end of neoliberalism, of a new compact between workers and capital, might age badly.

Still, it is improbable that Americans can lean on government as much as they have over the past year, and emerge unchanged. The significance of the New Deal was not just its effect on the Depression, which is still disputed, but its psychic legacy. Having seen active government at work, voters remained open to it for decades afterwards. It took the Opec oil crises and the rise of the New Right to break the Keynesian consensus in the 1970s. Together with the rest of the federal largesse since the pandemic began, the Biden bill could leave a cultural mark no less deep. People who have had their livelihoods saved are unlikely to forget it when the pandemic ends.

In a sense, Biden’s problems only start now. If the spending inflates prices, and overheats the economy, it will acquire all the public infamy it has so far dodged. Even if it doesn’t, he cannot allow extravagant borrowing to become the standard. The president has a duty to remind voters of that forgotten nuisance — the deficit — and to make hard choices to close it. Big government has to be paid for: taxes may have to rise on his watch. As a political feat, restoring the US to fiscal health seems fanciful. But then so, just weeks ago, did a relief bill of such ambition.

[ad_2]

Source link