[ad_1]

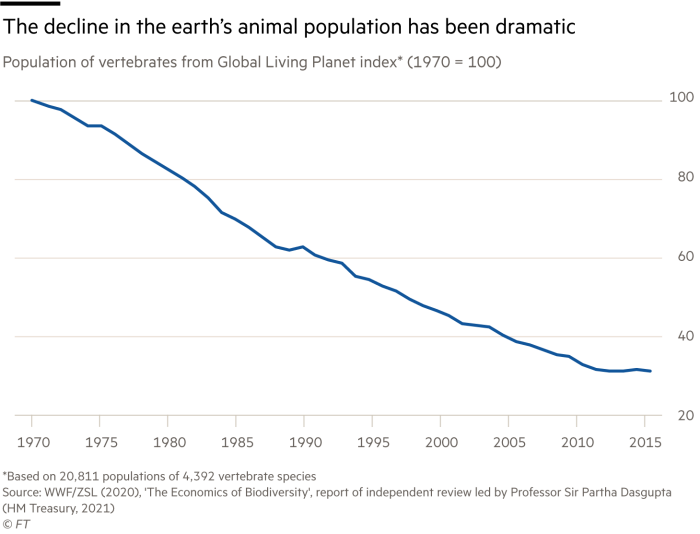

Today, human beings and the livestock we rear for food make up 96 per cent of the mass of all the mammals on the planet. Moreover, 70 per cent of all the birds now alive are poultry — mostly the chickens we eat. Extinction rates are also thought to be 100 to 1,000 times higher than their background rate over the past tens of millions of years. All this is a small part of our overall impact on the planet’s biosphere, the sum of all its ecosystems.

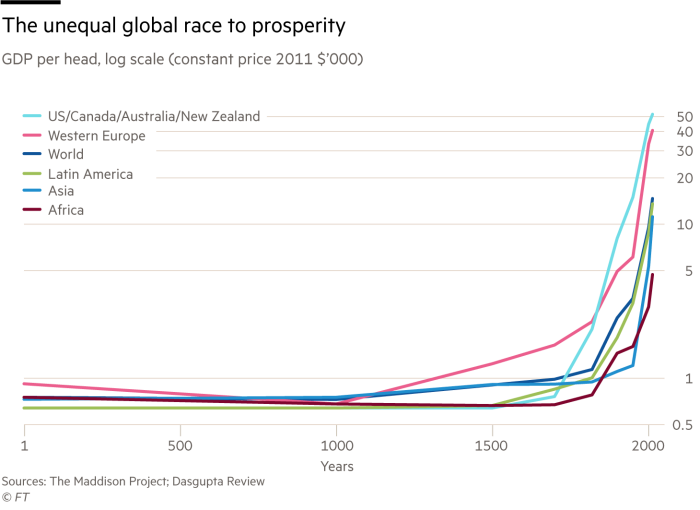

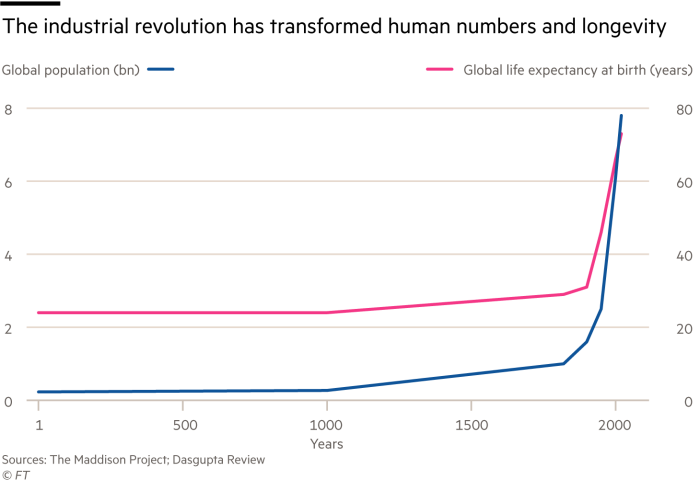

Humanity has become a cuckoo in the planetary nest. Our dramatic success in increasing our wealth and numbers has created a new age, sometimes called the “Anthropoceneâ€. This label may be an exaggeration. But that our activities are reshaping life on earth is no exaggeration. The question then is this: if we wish to reverse these threats, what must we do and give up?

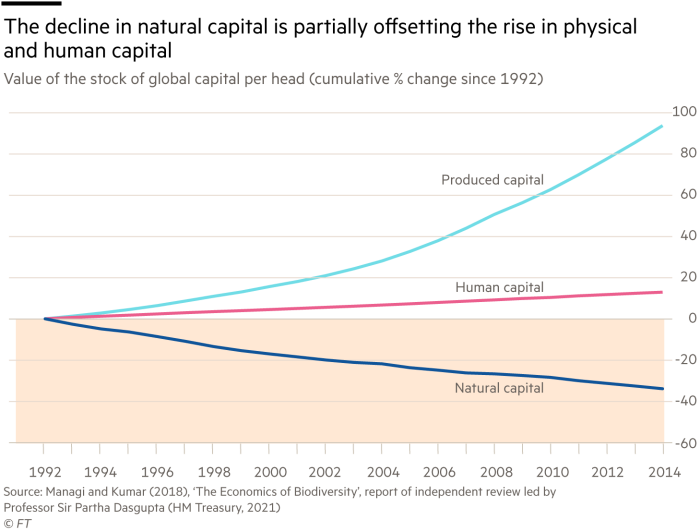

The remarkable facts noted above come from the foreword by David Attenborough to a definitive study of the economics of biodiversity, by Sir Partha Dasgupta of Cambridge university. It is no longer possible, Dasgupta argues, to exclude nature from our economic analysis. As his review states soberly: “At their core, the problems we face today are no different from those our ancestors faced: how to find a balance between what we take from the biosphere and what we leave behind for our descendants. But while our distant ancestors were incapable of affecting the earth system as a whole, we are not only able to do that, we are doing it.â€

In a fascinating recent lecture on “Techno-optimism, behaviour change and planetary boundariesâ€, the British economist Lord Adair Turner tackles head on the question of how best to manage the challenges. He notes two alternative approaches. One, which I would call “Onward and Upwardâ€, rests on faith that human ingenuity will find a way to solve problems created by human ingenuity. The other, which I call “Repent, For the End is Nigh†rests on the conviction that we must abandon all our greedy ways if we are to survive.

Helpfully, Turner transforms these contradictory attitudes into empirical questions: what will work, and over what time horizon? In answering them, he distinguishes physical from biological systems. The former are the ones that provide us with work, heat and cooling. The big challenge here is our dependence on fossilised sunlight, in the form of fossil fuels and their emissions of greenhouse gases. The latter supply us with the food we eat, as well as some textiles. The sun, water, minerals and the atmosphere are, needless to say, essential to life. But the transformation of these inputs into life itself involves biochemistry — the production of complex molecules by life itself.

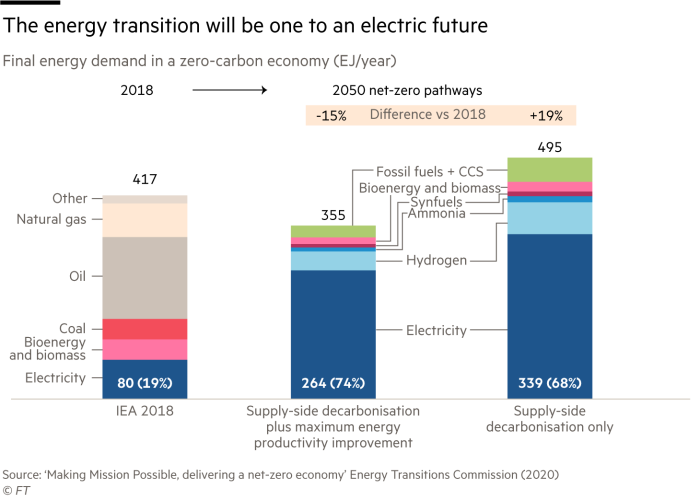

Making Mission Possible: Delivering a Net-Zero Economy, published by the Energy Transitions Commission in September 2020, lays out, Turner notes, a plausible passage to net zero emissions by 2050. At its core is a shift towards reliance on incident sunlight and wind, in the form of solar- and wind-generated electricity. This will be combined with batteries, hydrogen and other forms of storage, as well as a role for bioenergy and carbon capture in the medium run. Thanks to the collapse in cost of renewable energy, this transition is now both feasible and cheap. A few sectors, such as iron and steel, will be expensive to transform. But they are not large enough to change the big picture.

In brief, the physics of the energy transition is simple. The difficulty is shortage of time. We need to make large progress towards lower emissions over the next decade. But we cannot renew our entire infrastructure in so brief a period. So, in the short run, many will need to constrain their consumption. But, over the long run, the techno-optimists will be proved right on the energy transition.

Unfortunately, they are not (yet) right about the food transition. The problem is not the energy we need for food, which is just 6 per cent of total human non-food energy use. The problem is that photosynthesis and the conversion of plants into meat by animals are energy inefficient. So, biochemistry explains why humanity has had to take over so much of the planet. It takes huge areas of the solar receptors called plants to produce enough food and agriculture also emits large amounts of greenhouse gases.

Turner suggests a mixture of three solutions to this huge problem. The first is big improvements in agricultural practice. We are, for example, ruining land and replacing it with new land taken from other uses. Genetic engineering will surely play a part here. The second is changes in diet, especially away from meat and dairy. The third is radical changes in technology, ultimately turning the production of food into just another industrial process.

We are, in sum, at a historic juncture. It has fallen to our generation to take responsibility for the planet as a whole. There is no question that much of the response must be well-directed technological change, since no conceivable political process, least of all a democratic one, will meet these challenges by reversing two centuries of increased energy use. Humanity will not go back to its premodern existence, where life was nasty, brutish and short for almost all. But, given where we are now, in terms of our impact on the biosphere, we will also have to change our behaviour, at least over the short to medium run.

Whether it will be possible to agree and implement so radical a course correction is, to put it mildly, open to question. So far, we have shown next to no ability to resolve this huge challenge to collective action. But the need is obvious. We must not go on behaving as we have been. Many of us will need to change our behaviour and the richest among us will have to change most.

[ad_2]

Source link