[ad_1]

There is not enough serious discussion of freedom in the pandemic. Those who ostentatiously demand that concerns for liberty should guide our policy are not serious. Those who think seriously about policy, in contrast, think too little about liberty.

We should ignore the cartoonish libertarians who oppose lockdowns ostensibly to defend freedoms (often “British†or “American†freedoms at that, or some other supposedly essentialist right not to be told what to do). We know they are not serious because they resist mainstream scientific opinion about how the virus spreads and what sort of restrictions on physical proximity can keep contagion down. If you have to fit the facts to make your political preference easier to stomach — in this case by claiming there is no need to contain the virus — you are dodging, not engaging with, the hard question of how to weigh the value of freedom against the damage it can cause. Unserious people should not be taken seriously.

Real liberals do not dodge the question. That is why they have harder choices to make. They believe that the goal of politics is to give people as much control as possible over their own lives, but know that freedom’s value is no blanket licence to always do as one pleases. Effective freedom requires some rules and restrictions (even libertarians are not against jails), and a pandemic is itself a threat to liberty. There is no freedom for the dead or incapacitated. Effective liberty is reduced when healthcare provision is compromised, or when fear of contagion forces you to curtail the range of activities you can engage in.

Letting the pandemic rip through society is therefore not the pro-liberty choice. The question is how to control it if we want to put real freedom — everyone’s ability to be in control of their own life — first.

The classic statement of how liberalism should think about restricting individual choices is John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty: “The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.â€

Or as the more popular rendition of the same principle goes: “Your personal liberty to swing your arm ends where my nose beginsâ€, which we could update to our pandemic reality as saying that your personal liberty to spread airborne respiratory viruses ends with the air my lungs breathe in.

That brings us to the question of restrictions on travel, shopping, socialising and office work — anything that brings people physically close to one another. They obviously involve drastic interference with individuals’ choices as to how to behave. They can be justified, from a liberal perspective, only in a situation where uncontained contagion threatens people’s freedom and where they protect that freedom better than any of the policy alternatives.

Three principles are fundamental.

First, the measures must actually offer effective control of the pandemic while placing the least (or least serious) restriction on freedom possible. That entails, obviously, prioritising interventions that contain infection more strongly and infringe less on important freedoms. It is difficult to draw the line — but it should be straightforward to say that, for example, it is preferable to close pubs rather than schools.

More controversially, and paradoxically for liberals, it entails imposing tough lockdowns fast — which will reduce infection to lower levels sooner — rather than introducing restrictions in a more measured way. A liberal approach to interventions should judge them not just on how much freedom they take away, but how much freedom is lost now (and for how long) relative to how much freedom will be lost later (and for how much longer) in their absence. Where contagiousness is very high without restrictions, and prevalence would therefore grow exponentially, the answer is that less freedom is lost with earlier and more decisive (but therefore less enduring) action. Public health, economic efficiency and freedom all point in the same direction: towards an aggressive strategy of early suppression.

Second, however, liberals must press urgently for all other measures that can help make restrictions on freedom less necessary. Vaccines, the obvious example, come with liberal dilemmas: whether to make it compulsory, whether to allow the vaccinated the freedoms denied to the unvaccinated. It is harder to argue against the imperative of effective test, trace and isolate systems. Properly designed and implemented, they allow freedom-depriving lockdowns to be lifted. As Clemens Fuest of the Ifo Institute explains, they make it possible to swiftly open up activity in a targeted way — many indoor activities can be allowed, for example, and “green†restriction-free zones established, if access requires a negative rapid-test result.

Admittedly, test, trace and isolate policies bring liberal dilemmas too: testing may have to be compulsory, tracing involves surveillance and isolating requirements restrict freedom outright. In addition, it requires a firm lockdown first to bring the numbers low enough such that all cases can then be traced and contained (this strategy is variously called “zero Covid†or “no Covidâ€, depending on the country). But the infringements are much fewer and less intrusive than in longer, generalised lockdowns, and they are targeted to where they are individually justified.

The alternative is a “stop and go†of longer-lasting, broader restraints on individual choice, as economists Philippe Aghion and Patrick Artus insist in an op-ed: “Do we really think that Europe’s stop-and-go strategy, with the closing of culture, restaurants, curfews and stay-at-home rules, the impossibility of meeting family and friends, is less harmful to liberty than a zero-Covid strategy?â€

Yet the dilemmas reinforce the importance of the third principle: restrictions must be democratically controlled. Democratic control ensures that the process and not just the outcome of liberty is respected: you are freer if you impose restrictions on yourself than have them thrust upon you. Liberals can more easily accept limits on individual choice — provided they satisfy the two previous principles — that have been adopted through an inclusive democratic process.

Democracy also has pragmatic benefits. Scrutiny by eagle-eyed legislatures helps keep governments away from the temptation of mission creep — such as when many states explored infection warning apps that would unnecessarily centralise data. That is an argument for keeping governments on a tight leash by limiting the validity of special enabling legislation for restrictions to one month at a time. Strong transparency requirements help, too.

Why have so many countries failed to defeat the virus? In part because of the incorrect belief that intervening strongly would be worse for the economy, but also because of a misguided sense that it would unacceptably harm people’s liberty. In fact, liberty has suffered from governments’ unwillingness to act decisively but transparently in ways that would maximise it. The cause of freedom would benefit if liberals made that case more loudly.

Other readables

Numbers news

-

The New York Times’s Matina Stevis-Gridneff reports that amid accusations of vaccine nationalism, the EU exported 25m doses of Covid-19 vaccines in February — more than the number its own citizens received. This includes 8m to the UK, equivalent to three-quarters of the jabs the British health service administered that month.

-

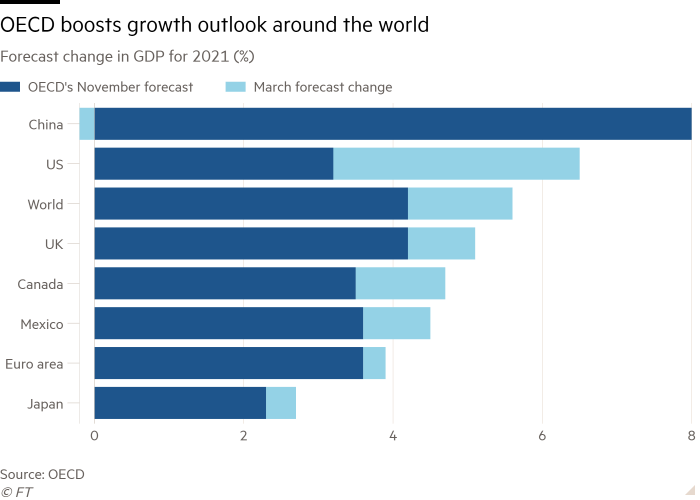

US president Joe Biden’s fiscal plan will raise global growth by more than 1 percentage point this year, according to the OECD’s updated economic forecasts. It more than doubles its forecast for America’s own 2021 growth rate.

[ad_2]

Source link