[ad_1]

Last Sunday, in common with a lot of people in America, I settled down in my living room to watch the Oprah Winfrey interview with Meghan Markle and Prince Harry. Not because I’ve ever signed up to “Team Meghan†or even followed the couple’s story with any closeness, but because I was curious to hear how much they would share publicly about their experiences with regard to race.

As I listened to Markle, and all the heartbreaking things she disclosed about her experience, I heard her say something that seemed to sum up what was at the core of everything she was describing. “It was all happening,†she said, “just because I was breathing.â€

I suspect that in countless homes across America, black people heard that and either sighed deeply and shook their heads or simply felt within themselves a point of recognition. Markle was insinuating what is basically the experience of the majority of black people living in the western world — the recognition that her being black was going to be an ongoing cause of various levels of mistreatment and disregard.

The details of her experience may have seemed jaw-dropping to many, unable to imagine that kind of reality. But for a black person, Markle’s claims weren’t shocking in their scope. Black people know on an almost daily basis what it is like to exist in a world conditioned to devalue your existence because of the colour of your skin. It is a real and consistent reality.

If anything was surprising to me, it was that Markle chose to air this publicly about such a powerful and public institution, in the knowledge that the majority of people will neither be able to understand nor empathise with her experience.

It is an act of self-care not to constantly re-live traumatic experiences — and, for black people especially, not to feel obliged to justify or defend your experiences of what it is like being black in a world that still operates in many ways out of false, damaging, even life-threatening narratives about black identity. But, I suspect, sometimes we speak our truth because it needs to be heard, more than we need to tell it.

We best understand the world from our own vantage point. Yet we listen to other people’s stories in order to recognise and remember that our experiences, viewpoints and, most significantly, realities are not the sole ones. Acknowledging another human being’s experience does not mean denying your own. But it does mean being open to having your sense of the world questioned, especially if your perspective has been the dominant one for most of history.

When public outcry and protests were sparked across the US last spring in the aftermath of the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, some people found themselves saying, “This isn’t America. This isn’t the country we stand forâ€. But for many black Americans, it was the only America they recognised.

As I was thinking about the interview over the past few days, and how uncomfortable it seems to have made so many people, an image of Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With†(1963) flashed across my mind. The New York-born artist knew about the power of art to craft narratives about people and the world. For almost 50 years he made a living telling visual stories through his illustrations on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post magazine, summoning up images of a pristine, neighbourly, all-white American existence. It was what people wanted to see and believe, a candy-coated vision of America.

For most of his time at the Post, Rockwell said he was allowed to portray black characters only in service industry positions. But in 1963, he left the Post for Look magazine, and within a year, at the age of 69, he felt angry enough about the reality of racism in America that, with the blessing of his new employer, he started making new work that expressed his growing sentiments.

“The Problem We All Live Withâ€, now permanently housed at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, appeared in the January 14 1964 issue of Look magazine. It was a glimpse of events in November 1960, when a six-year-old black girl, Ruby Bridges, was escorted by US marshals to the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, following the US Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling that segregated schools were unconstitutional.

Shown from a child’s viewpoint, we see the girl dressed all in white, walking confidently between four white adults, the marshals appointed to protect her from a screaming mob not shown in the illustration, but seen in black- and-white photographs of the real event. What we do see of the mob is evidenced on the gritty concrete wall in the background of the picture: large scrawled graffiti spelling out the N-word, right above the child’s head, the letters KKK on another side of the wall, and the smeared remains of a thrown tomato running down the part of the wall behind the child, a burst of colour in an otherwise neutral palette.

I thought about this image as I considered a few things from the interview and the reality of the world. The title of this illustration is just as important as the image. Racism affects everybody because it affects how the world is run — but depending on where you stand in proximity to it, you feel it more or less acutely. Harry shifted a little bit closer to it in marrying Markle. He says as much. By her side, he got a closer look at the reality of racism and the extent to which it still prevails. He saw another version of the story about blackness than he had been told.

Some readers were appalled by Rockwell’s painting, probably because he had tarnished the view of the America they knew and wanted to remain in, and because it was unpalatable to talk about a race problem that could, again depending on your proximity to it, be ignored.

I thought, too, of what Markle shared about her fear of not being protected. There are so many black women (and men) who want the ideological equivalent of the physical protection Ruby Bridges had. Because part of the reality undergirding some of her remarks is that the western world is not conditioned to protect black bodies, least of all those of black women. It’s actually the opposite. Though such a statement might elicit discomfort or denial from some, it is evident in the history we stand on.

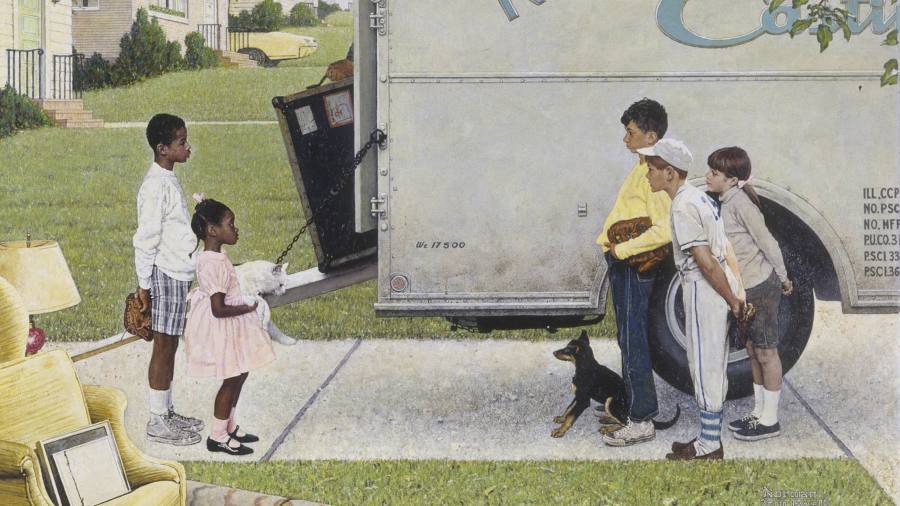

In 1967, Rockwell illustrated a piece about “white flight†and suburban integration with a picture he called “New Kids in the Neighborhoodâ€. I remember the first time I saw this image was at a poster sale in the university commons during my freshman year of college. I was so moved by it that I bought it for my dorm room, and all this time later, I still have it.

It’s a wonderfully suburban scene of a middle-class family moving into a new house. The two children, a boy and a girl, stand in their driveway as a mover unloads the truck. The children are dressed as you might expect: the boy in shorts and Chuck Taylors, with a baseball glove in his hand; the girl in a pink dress, with matching pink socks and bow in her hair. A perfectly normal image. Except it’s the 1960s and the new family is a black family.

Standing across from the black children are three white children of similar age. One boy has his own baseball glove under his arm, while the girl wears a pink bow in her hair. The children peer at each other, two of the white children leaning in for a closer look.

There is nothing to suggest animosity between them. In fact what sticks out is the posture of curiosity of the white children, a genuine interest in something foreign to their experience. The black children stand almost to attention, already so used to being gazed at and estimated. In the top left-hand corner of the image, an almost imperceptible white face peers out at the kids from behind a curtain. The old guard watching the potential future and not necessarily liking it. Rockwell’s work reminds me that no matter how far we think we’ve advanced, there are still well-guarded boundaries about who’s allowed where and how far in they are allowed.

I remember almost three years ago, when millions around the world sat transfixed in front of their TV sets, as Prince Harry and Meghan Markle married at Windsor Castle. Eager to proclaim that a more diverse future was here, people celebrated the presence of a black choir, and applauded the sermon delivered by Bishop Michael Bruce Curry, the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in the US.

Again, a painting by Rockwell springs to mind: a work called “Golden Ruleâ€, which appeared on the April 1 1961 cover of the Saturday Evening Post. It portrays 51 people of different races and ethnicities, and was inspired by the mantra of doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. It is a beautiful image, an ideal to aspire towards, a world where people of all backgrounds can coexist in just societies, and within systems that regard and treat everyone as equal.

You can stand before this painting and feel hopeful for a moment because it offers a glimpse of what could be. But unfortunately such moments cannot erase what still is.

Enuma Okoro is a writer and speaker based in New York. On March 18, she will be in conversation with artist Rachel Whiteread and FT arts editor Jan Dalley, as part of the FT Weekend Digital Festival

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

[ad_2]

Source link