[ad_1]

It is a year since I packed up my laptop and left my desk in London, with its stunning view of St Paul’s Cathedral. I have been back once. Barely a day has passed when I have not read, or written about, the future of offices.

Employers have a lot invested in office property. But they should be more exercised about how staff spend their time once the pandemic lifts, than whether they sit in sanitised cubicles or at socially distanced hot-desks. The prize will go to the enterprise that can make the most of how its workers use their limited hours, as it always has.

I still remember when my father came home from the textile company where he worked to say he had shifted to a newfangled system called “flexitimeâ€. That was the mid-1970s, around the time flexible working, pioneered in Germany, earned a mention in a Financial Times analysis of “the way to better staff moraleâ€.

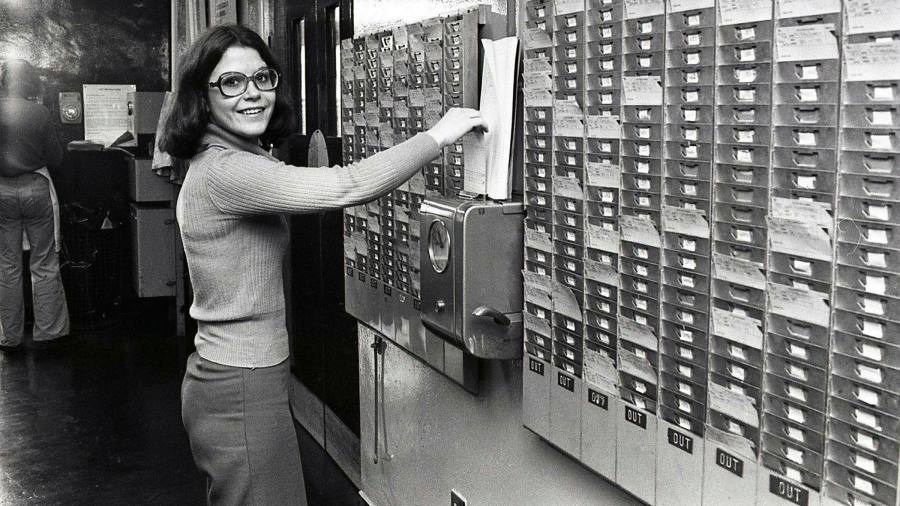

Flexibility only went so far (and it certainly wasn’t enough to save the UK textile industry). Wary employers monitored flexible hours with the same clocking-in system previously used to police the 9-to-5 regime. These days, they are more likely to deploy sensors to regulate who is where, and when.

The difference is that remote-working employees have learnt in the past year to relish flexibility. While writing this column, I cooked a lamb tagine. It was no great culinary feat, but until last March, the challenge of combining overnight marinating and on-the-day prep work with the commute would have deterred me. I couldn’t simply step away from my desk in head-office to season meat and fry onions, returning to carry out an interview once the meal was safely in the oven. Now not only does my family eat more home-made meals, I am calmer for having cooked them. “Staff morale†is up.

I would be loath to lose my flexitime. But compromise will be necessary as more normal business resumes and that will be difficult for companies to manage. It was hard enough, after all, to juggle the various permutations of holiday leave, business travel, and multiple in-person meetings before the pandemic further blurred the boundaries between office and home.

Online tools and apps are no solution. “The technology era has made us feel as though there’s no time budget but of course there is,†says Julia Hobsbawm, author of “The Nowhere Officeâ€, a new paper about the future of work for the think-tank Demos.

Zooming and emailing, walking and conference-calling, even cooking and columnising, may work for some people, some of the time, but productivity and creativity are bound to suffer in the long term if staff simply double the tasks they aim to complete within the same fixed schedule.

Instead, employers and employees need to return to first principles — and make some hard choices. “You have to be much more thoughtful about how you use time and place, and at the centre is a question of what helps the person be productive,†says Lynda Gratton of London Business School. In a forthcoming article for Harvard Business Review, she points out the importance of understanding how working arrangements affect the drivers of productivity, such as energy, focus, co-ordination, and co-operation. Fujitsu of Japan has over the past year developed a “borderless office†for hybrid workers. Staff can shift between hubs, satellites and shared offices (for those with inadequate quiet space to work at home), according to need.

Lockdown has already introduced workers to new ways of working. Harvard’s Leslie Perlow and colleagues Ashley Whillans and Aurora Turek studied staff at a professional services firm last spring. These knowledge workers lamented, as many have, the sudden reduction in spontaneous exchange of ideas. But when they collaborated using Slack, their work improved because they had more time to think. Before companies start obliging staff to gather regularly for in-person brainstorming, they should consider whether working out of sync might yield better results.

Finally, brutal work schedules could themselves be pruned. In a 2009 study of consultants at Boston Consulting Group, Perlow and Jessica Porter found cutting hours had many benefits, but they had to impose a predictable schedule of time off to persuade driven professionals to reap the benefits of a lighter schedule. Similarly, in a hybrid world, middle managers may remake themselves as facilitators, nudging staff to use their time better.

Chief executives have an important role, too, Gratton points out. They must decide how staff should deploy to meet the culture and post-Covid objectives of the business.

A few bosses might conclude they should urge workers back to the office. But if they allow the choice to be dictated solely by the company’s real estate footprint, they will almost certainly be making the wrong decision.

Twitter: @andrewtghill

[ad_2]

Source link