[ad_1]

When the cryptocurrency evangelist Anthony Pompliano wanted cash to buy more bitcoin, he turned to a centuries old financial practice that has suddenly found a new audience in Silicon Valley.

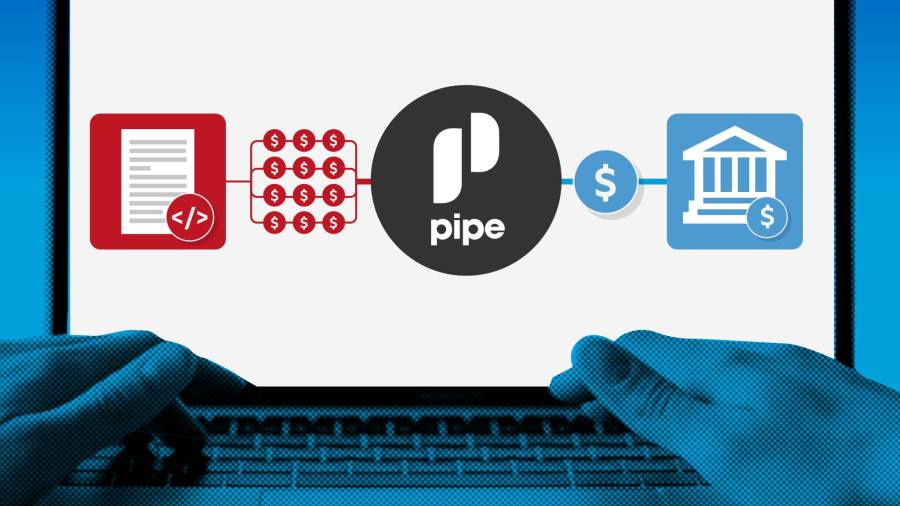

In a few hours, Pompliano sold the rights to some of the future subscription revenues from his email newsletter, The Pomp Letter. The middleman was a two-year-old company called Pipe that connects businesses with investors offering to purchase their future revenues at discounted prices.

“This was me. I sold my recurring revenue to get cash upfront,†Pompliano wrote on Twitter, after Pipe’s chief executive revealed anonymised details about the transaction. “Then I bought more Bitcoin.â€

Pompliano’s transaction was an extreme example of how the familiar practice of invoice factoring, more commonly used by manufacturers, is now being applied to tech start-ups who want fast cash without the expense of raising venture capital.

“I think we’ve unlocked the largest untapped asset class in the world,†said Harry Hurst, the chief executive of Pipe, who claimed that his company plans eventually to securitise the revenue streams on offer. Investors can already buy and sell contracts in secondary trades on the platform, he said.

Last week, a group of blue-chip backers including the workplace chat app Slack, ecommerce platform Shopify and Salesforce chief executive Marc Benioff provided a vote of confidence in the start-up, investing $50m, some of which went to purchasing shares from existing shareholders.

Hurst said hedge funds and other institutional backers had also committed more than $1bn in capital to the market, and transaction volumes had more than doubled every month since June to tens of millions of dollars.

In five years, Pipe will have facilitated “hundreds of billions of dollars in trading volumeâ€, he said.

Hurst’s ambitions reflect the enthusiasm investors have shown for subscription-based software businesses, which have revenue streams that some have said are as trustworthy as debt payments.Â

The market capitalisation of public cloud software companies more than doubled to $2.2tn during the past year, according to the Bessemer State of the Cloud report, underlining the value that has rapidly accumulated behind their business models.

But some finance experts warned that subscription revenues are not ready to be turned into an asset class in their own right. Pipe’s deals can also be costlier than traditional debt, and investors may have limited options if the companies backing the contracts go out of business.

Companies on Pipe typically sell their monthly or quarterly subscription revenues at 2 per cent to 8 per cent discounts to the full annual value, with the start-up taking a cut of the transactions.

Michal Cieplinski, chief operating officer of Pipe, said the deals qualify as “true sales†that transfer rights to the income streams from a company to investors. Companies on Pipe do not have to alert customers about the deals.

Buyers can make internal rates of return above 10 per cent if they purchase contracted revenues on Pipe at 95 cents on the dollar, said Justin Saslaw, a former investor at hedge fund executive Jim Palotta’s Raptor Group.

“If you can get a diversified bundle, these cash flow streams really become attractive,†said Saslaw, who recently joined Chamath Palihapitiya’s Social Capital. Raptor helped lead Pipe’s latest financing and is one of the largest buyers on the platform.

But John Griffin, a professor of finance at the University of Texas at Austin who has researched asset-backed securities, said the complexity and variability of software contracts might not make them suitable for securitisation.

Griffin said it could be difficult to monitor the performance of the contracts, noting that they vary widely depending on the nature of the business and many start-ups fail.

“I don’t see how they can be easily securitised and receive credit ratings,†Griffin said. “They might be, but it seems like a recipe for disaster.â€

Hurst said buyers on Pipe would only lose money if companies stopped servicing customers. If an underlying customer cancels its subscription, companies using Pipe have to replace it with a contract of equal value or rebate the difference in cash.

“What we’ve unlocked is one of the most highly predictable, secure assets,†Hurst said. Investors have not experienced any losses since Pipe opened on a limited basis in February last year, according to the company.

Under the costliest scenario, companies that sell their monthly contracts at 92 cents on the dollar on Pipe would pay the equivalent of more than 15 per cent in interest per year, according to Financial Times calculations.

By comparison, lenders to venture-backed companies typically charge interest rates of 6 per cent to 13 per cent and receive warrants that can convert to a small stake in the start-ups.

Pipe said it was “significantly cheaper†on average than venture debt providers, when accounting for the impact of warrants and loan covenants.

Some venture capitalists drew comparisons between Pipe and LendingClub, the one-time Silicon Valley darling that attempted to create a new marketplace for personal loans but ran into problems after listing publicly in 2014.

Investors valued Pipe at $140m after a seed round of financing last year, according to incorporation documents and a person briefed on the deal, about 10 times the typical valuation given to similar sized start-ups. It was unclear how Pipe’s valuation changed with the most recent round of funding.

Pipe’s investors rejected the notion that the company could run into difficulties growing its trading platform.

Jillian Williams, a principal at the venture firm Anthemis who led its investment in Pipe, said companies using Pipe were aligned with investors on the other side of the transactions. “With LendingClub, a lot of that didn’t necessarily match up in the same way.â€

[ad_2]

Source link