[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Welcome back. Yesterday I argued that the decline in some technology shares was evidence that we are “selling insanityâ€. That this is not true everywhere was proved by Wednesday’s market action in meme stocks, which looked plenty nuts. Today I look for reason amid the madness.

Comments on Unhedged? Email me: robert.armstrong@ft.comÂ

AMC’s popcorn paradoxes

Here’s a good point, from the economist Peter Garber:

“Before we relegate a speculative event to the fundamentally inexplicable or bubble category driven by crowd psychology, however, we should exhaust the reasonable economic explanations . . . ‘bubble’ characterisations should be a last resort because they are non-explanations of events, merely a name that we attach to a financial phenomenon that we have not invested sufficiently in understanding.â€

We were reminded recently of the importance of this commandment — call it “Garber’s rule†— by the Hertz bankruptcy. Oh, how we smart people laughed at the poor stupid retail investors who bought Hertz shares after it filed for Chapter 11. But then the investors made a nice recovery in the bankruptcy, and they laughed at us, instead.

To put the same point differently, for a person who makes a living trying to understand financial markets, saying “it’s just a bubble†is saying “I quitâ€. And Mrs Armstrong didn’t raise quitters.Â

So bear with me as I try to make sense of what investors are doing here:

-

On Friday afternoon, at about $26 each, AMC Entertainment shares looked like a standard overpriced meme stock, having run up from a low of $2 late last year. It’s a cinema chain, so it had a bad 2020, but it was taking on water before then, in part because of high debt. It lost money in both 2017 and 2019;

-

Then, on Tuesday morning after the long weekend, AMC announced it had sold 8.5m new shares to a hedge fund, Mudrick, for $230m, or about $27 apiece;

-

After news of the sale — which diluted existing shareholders’ ownership of the company — the shares rose, closing on Tuesday at about $32;Â

-

Then, later on Tuesday, came the news that Mudrick had sold all the shares it bought already, locking in a profit. The fund considered the shares overvalued;Â

-

On Wednesday, the stock rallied furiously, closing at $65;

-

Also on Wednesday, AMC announced it would offer retail investors free popcorn.

That last move by AMC is obviously a taunt aimed at those of us who still believe in economic rationality. But let’s rise above it, like professionals, and try to make sense of what AMC investors are doing here.

(What Mudrick and AMC are doing is obviously rational, of course; they are getting while the getting is good.)

Corporate finance 101 says that any corporate investment project where the prospective returns are greater than its cost of capital increases the value of the company. AMC just raised some very, very cheap capital, which means it should be able to invest it at an excellent return. This is the best cornerstone we have for a fundamental case for owning the stock: AMC is a company that owns a magic money tree (owning a company at a high price because other investors are willing to own it at a high price sounds circular, and probably is, but stick with me for a minute).

Just how cheap was the new capital? A very crude way of measuring the cost of equity capital is with the earnings yield, which is just the price/earnings ratio turned upside down. It tells you how much of the company’s earnings each new share is entitled to, as a proportion of the price paid. This is slightly tricky in AMC’s case, because it made losses even before the pandemic. But the company did make a $110m profit in 2018, and generated almost as much little free cash flow (cash earnings, if you will) in 2019. Using those historical earnings as the numerator, I arrive at an earnings yield/cost of capital well under 1 per cent. This money cost almost nothing.

(I’m aware there are more grown-up ways to determine cost of equity, such as the capital asset pricing model, that would result in a much higher cost of capital, say 7 per cent. I’m not impressed by this. AMC just raised this capital, at a high price, on the basis of de minimis expectations for earnings. The money was all but free, people, whether your finance professor likes it or not.)

Now, access to cheap capital is not very helpful if you have no good investment opportunities (just ask a big American bank). AMC says it is going to use the money to buy new cinemas from struggling rivals, but it has a much higher-returning option than that: its own debt.

Annualising the interest expense the company paid in the first quarter, it looks like the company pays a blended interest rate of about 11 per cent. Raising equity at current prices and paying that down, it is making an epic spread of more than 10 per cent.Â

How much new equity would AMC have to raise to eliminate its debt? Excluding its $90m in operating leases, the company has $5.5bn in debt and has $800m in cash on hand. Say it uses all the cash to pay down debt, then sells shares at $60 (a discount to yesterday’s close) to pay down the remaining $4.7bn. That would require 78m new shares, on top of the 409m outstanding currently.

(Is all of this wildly speculative? Sure. Is it missing important details? You bet. Could this wobbly company really get almost $4bn in new equity from the market? It would be hard. But the whole point here is pushing the argument as it will go.)

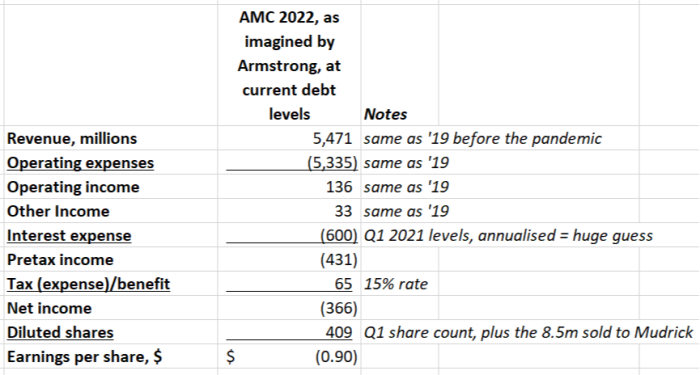

Here’s the numbers, as I see them. If AMC returns to 2019 levels of revenue next year, and maintains its current debt levels, its income statement will look something like this, as far as I can figure:

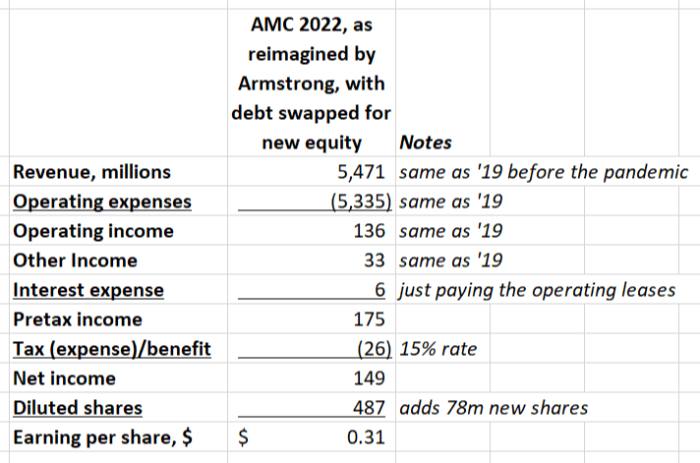

Now imagine they raise all that new equity at $60 a share and pay down all the debt except the leases. Then the P&L looks something like this:Â

AMC is suddenly profitable! The retail investor, by providing the company with cheap capital, has bootstrapped the company back into the black. Except, of course, for one little problem: those inventors are now holding a stock which, at $60, trades at more than 200 times earnings, and that looks like a bubble. Even with the most pliant of investors, recapitalising your way to a sane valuation is hard.Â

To bring that ratio down it could sell still more equity and invest it again, in something new. But at some point, we must assume, the market would be tired of giving AMC all-but-free money. I think I will quit now. Sorry mom.

One good read

Yesterday I wrote about Howard Marks’ argument that we are now in a “low return worldâ€. As it turns out, Marks is hardly the only investor who sees it that way. My colleague Robin Wigglesworth has written a story about some others here.Â

[ad_2]

Source link