[ad_1]

China’s odyssey to the moon and back has given Beijing global bragging rights and boosted national pride and patriotism. Yet there are key aspects of China’s most challenging lunar mission ever that state media has barely mentioned.

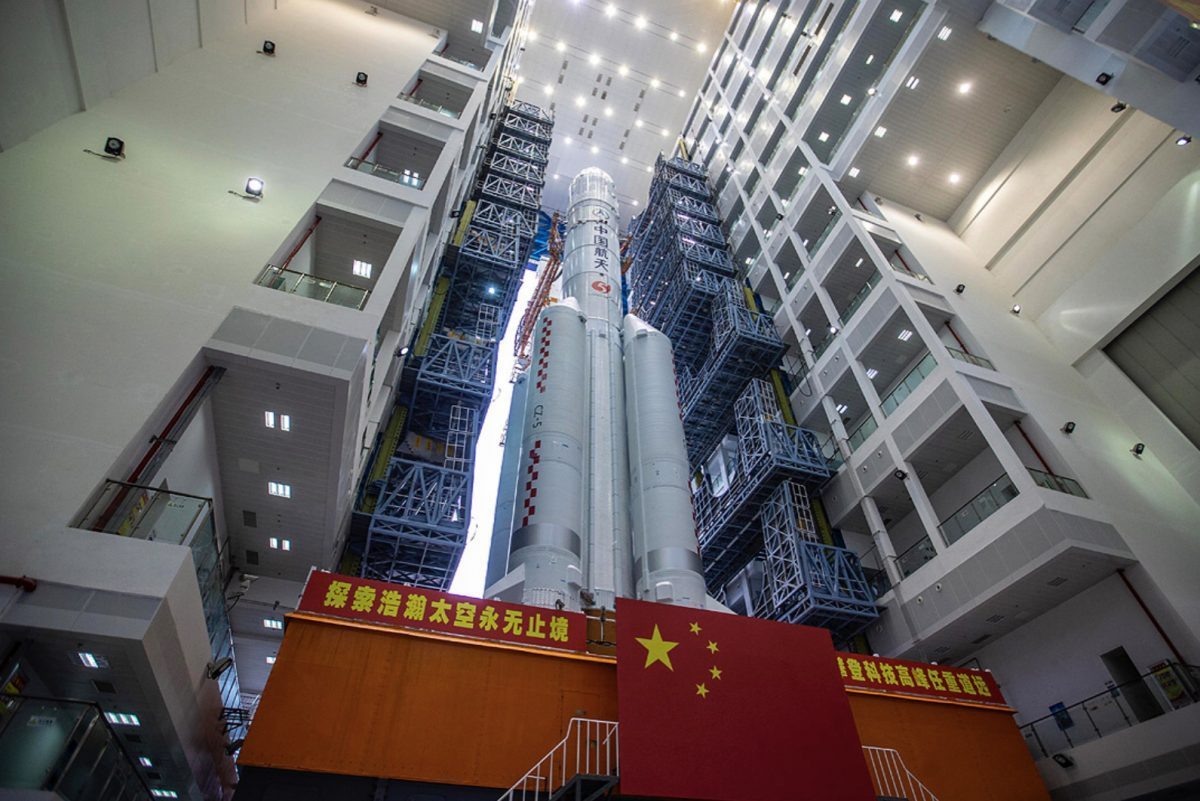

On the surface, nothing dramatic occurred outside Beijing’s script for the Chang’e 5’s 23-day, 726,000-kilometer round trip. The probe blasted off from the southernmost island of Hainan on November 24, touched down on the lunar surface a week later, dug up soil and dust, rocketed back and parachuted into Inner Mongolia on December 17.

The three probes that have landed on the Earth’s closest celestial body in the 21st century all bear the Chinese flag and the name of Chang’e. The 1.731 kilos of lunar soil and dust brought back by Chang’e 5 were from the first lunar sample mission since 1976.

But soon after the Long March 5 transport rocket launched from Hainan to shoot the Chang’e 5 payload into the low-Earth orbit, the mission’s ground control in Beijing would have gone deaf and blind had it not been for the vital signal tracking and relay service from the European Space Agency (ESA) Kourou Satellite and Aerospace Station in French Guiana, a territory in South America bordering Brazil and Surinam.

Beijing-based Lifeweek magazine, printed by state-owned China Publishing & Media Holdings, revealed this month that the ESA relayed several hours of critical signals from the Chinese probe while it was on its way to the moon for cadres and engineers with the China National Space Administration (NSA) to track the position and status of the 8.2-tonne spacecraft and make sure it did not drift off course.

The ESA also noted in a readout in November that its Kourou Station’s S and X-band dish antennae supported the launch and early orbit phase telecommand for the Chang’e 5.

Part of the Chinese probe’s return leg was also guided by the ESA’s Maspalomas Ground Station on the Island of Gran Canaria, in Spain’s Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, where S and X-band signals were picked up and relayed to Beijing.

It is also speculated that, had it not been for the China exclusion bills imposed by the Barack Obama administration in 2011 to sever ties with China in space exploration, Beijing would have also sought help from NASA to track the Chang’e 5’s high-wire lunar feats: its descent to the lunar surface and the return capsule’s rendezvous with an orbiter waiting 200 kilometers above the surface.

Beijing initially thought NASA’s lunar reconnaissance satellite could form a backup layer of monitoring and step in to recalibrate if any part of the Chang’e 5’s auto navigation and positioning system failed, given the delay in direct communications between the probe and Beijing’s ground control.

State broadcaster China Central Television once noted in a program about the mission that the lunar orbit rendezvous margin of error was just five centimeters. Still, despite the legal constraints, NASA’s satellite managed to snap a few photos of the Chang’e 5 after it landed on the moon.

On January 18, NSA director Zhang Kejian convened a commendation ceremony at the National Astronomical Observatory in Beijing attended by representatives from the ESA, the European Union as well as Pakistan’s Committee for Outer Space and Atmospheric Research, Argentina’s National Committee on Space Activities and Namibia’s Ministry of Higher Education, Training and Innovation.

Zhang thanked these partners for their “indispensable help and input†in telemetry and communications for the Chang’e 5’s mission while hailing the spirit of international collaboration in remarks that also took a swipe at the US’ China exclusion policy.

It is also said that after helping Beijing track and talk to Chang’e 5, the ESA signaled its interest to Beijing to get a small portion of the lunar soil sample for study by EU scientists.

Meanwhile, talk in China about giving samples to friendly Western powers to break the US-led iron curtain on tech and space cooperation has been revived after Zhang released details of a by-law governing extraterrestrial sample research and exchange.

Still, Zhang did not respond to questions from foreign reporters about which country would be the first recipient and why the amount collected on the moon was noticeably smaller than intended. The Chang’e 5’s container could carry up to two kilos of samples but the probe only returned 1.731 kilos.

Hou Jun, chief of the NSA’s lunar program and top commander of the Chang’e 5 mission, revealed during a seminar in late December that the robotic arm of the probe, designed to drill about one meter into the lunar surface, hit “a big lump†and could not penetrate deeper.

“For the sake of retrieving all the samples already collected and not to damage the robotic arm and even the entire lunar lander, we sought permission from the NSA and state leaders overseeing the entire mission to stop drilling the encrusted surface and seal off the container well ahead of the original schedule,†Hou said.

He added that the NSA had not concealed the obstacle in sample collection and stressed that the lower-than-expected amount should not be construed as a failure because it was a “force majeure event,†stressing that the performance of the Chang’e 5 had “blown past all design parameters and expectations.â€

The 1.731 kilos, nonetheless, pales in comparison with the hauls from America’s Apollo program spanning the 1960s and 70s. The six US manned missions brought back a total of 381 kilos of lunar soil and rocks. The US also donated about one gram to China before both countries formed diplomatic ties in 1979.

Hou argued, however, that the Chang’e 5 sample collection was fully automatic and the container was deliberately not to be filled to the brim as part of a “system redundancy design.â€

“When China can dispatch its own group of taikonauts to the Moon in the next decade or two, more decent amounts can be dug up and brought back because future spaceships being designed will be big enough to be stuffed with samples,†Hou said.

After the homecoming of the Chang’e 5’s return capsule, the probe’s orbiter continues to circle the Moon and flies over the two other Chinese landers still on the surface.

The Chang’e 3, launched at the end of 2013, has spent years surveying a small portion of the Mare Imbrium, one of the largest craters in the Solar System while the Chang’e 4 is sitting dormant after landing on the moon’s dark side in December 2018.

[ad_2]