[ad_1]

Nobody knows how the economic world will look half a century from now. One can make more or less informed guesses. But ultimately they will just be guesses. Data we have from the past provide a rough guide. But the notion that we can draw reliable probability distributions over long periods ahead is nonsense. Yet we still have to make decisions that relate to longtime horizons. Climate change is an example. Another is pensions.

The destructive outcome of being precisely wrong rather than roughly right was the subject of my column two weeks ago. I noted that the desire to make private-sector defined benefit pensions plans safe had rendered them unaffordable. The perfectly safe and generous pensions that regulation sought to protect are disappearing from the UK. This leaves almost everybody who now works in the private sector relying on a paltry state pension, inadequate and insecure defined–contribution pensions and whatever other assets they may own. According to the UK’s Pension Protection Fund, only 1m people today accrue new benefits in the defined-benefit schemes it covers. That is just 11 per cent of all scheme members. The rest are retired or deferred. The best has been the calamitous enemy of the good.

How did this sorry tale happen? The answer is: inappropriate institutions; foolish goals; and bad economics. All of these are related to the issue of uncertainty, as is explained in Radical Uncertainty by John Kay and Mervyn King.

The most important way for humans to cope with uncertainty is through institutions. But companies were always the wrong institutions for providing pensions. They are not secure enough to fulfil such a long-term contract. Moreover, there are conflicts of interest between shareholders and current and future pensioners. That reality has justified the ever more onerous regulation.

The problem with goals is that the cost of providing a given income up to 70 years into the future is unknowable. But the more certain achieving a specific target is made, the costlier it will be.

The problem with the economics is that it does not allow people to make needed judgments in a sensible way. A sobering and significant illustration comes from the mess that is currently being made of the Universities Superannuation Scheme, which has 460,000 members and £79bn. This is a giant scheme. Moreover, universities are ideal institutions to run a pension system.

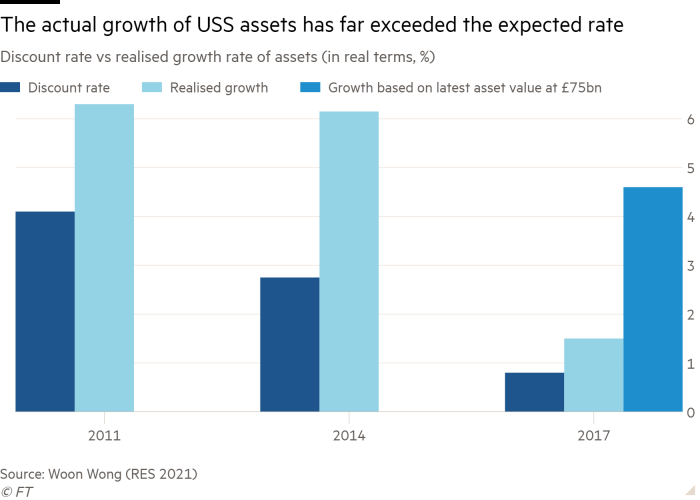

Yet, between March 2018 and March 2020, or just two years, the “technical provisions†deficit in the USS has jumped from £3.6bn to £16.1bn. As a result, say the trustees, “the overall contribution rate would need to rise to 42.1 per cent of payrollâ€. The latter currently stands at 30.7 per cent of payroll and was already due to rise to 34.7 per cent under the 2018 valuation. So, the required contribution rate must jump from high to unaffordable. (See charts.)

Why? The explanation is changes in assumed discount rates, due to the fall in real interest rates on UK government gilts into highly negative territory during the pandemic. Why on earth should this exceptional event determine discount rates far into the future? Fundamentally, any precise calculation of the deficit for such a scheme is worthless. A silly question has to get a silly answer.

Woon Wong, of Cardiff Business School, argues compellingly that, on sensible assumptions, the scheme is in comfortable surplus. He estimates that the rate of return on investment needed to equate the present value of liabilities to the value of assets is a mere 0.7 per cent, in real terms. Given the time horizons of this scheme, even a huge bear market would not threaten its ability to meet its obligations. The only assumption under which the USS scheme could fail is a permanent end of economic growth. In such a world, even government debt now thought “safe†would cease to be so. The safety regulators and trustees desire is a mirage.

If the aim of regulation is to ensure that a scheme can meet its obligations in any imaginable state of the world, then all such schemes are going to disappear, making real people far worse off than they need to be. In the case of the USS, the right option is to make conservative, but not insanely pessimistic, assumptions and conclude that it is healthy.

Nevertheless we do have to assume that most private-sector, defined-benefit schemes will die, for both good and bad reasons. What should replace them? A sensible answer would include greater flexibility than in the old defined-benefit schemes. Yet we also need true risk-sharing within and across generations, which is absent from today’s defined-contribution schemes. I will return to the topic of what this new approach should look like.Â

[ad_2]

Source link