[ad_1]

It is the most talked about and yet most invisible interior in recent British history. The prime minister’s upgrade of his flat in 11 Downing Street has been causing a furore and we are naturally curious.

A quote referring to Theresa May’s “John Lewis nightmare†(which now doesn’t appear to have come from Carrie Symonds) triggered a tsunami of tongue-in-cheek tweets and some expert-level trolling from the department store’s social media team. For example: “We pride our Home Design Service on having something for *almost* everyone†and a photo of a JL van in Whitehall tagged “Good thing we have a recycling service for old preloved furniture.â€

The balm to the furniture nightmare, we will be glad to know, has been concocted by interior designer Lulu Lytle. With her shop Soane Britain on Pimlico Road, a brisk stroll away from Westminster, Lytle has built her business into a very British cocktail of country house, colonial influence and folksy craft.

The coincidence is that she adopted the name of Britain’s most brilliant architect, Sir John Soane (1753-1837) for her business. Soane was the architect who designed the Bank of England and had it depicted as a ruin by the painter Joseph Michael Gandy. It was Soane who designed the elegant state dining room at Downing St with its shallow vaulted ceiling and delicate plaster decorations.

In the vacuum of images of the much talked-about makeover, commentators have been scavenging pictures from Lytle’s website and Instagram feeds to gather clues as to what might have happened upstairs in Downing Street.

One image in particular, of a vivid floral sofa and matching wallpaper and lampshades, seems to have become almost accepted as a surrogate photo of the Johnson/Symonds home, though it is actually a shot of Lytle’s own home in Bayswater (which she shares with her husband, Goldman Sachs senior investment banker Charles Patrick St John Lytle).

As we don’t have much more, all we can do is peek into these images of her taste in designing for an ideal client — herself.

Anyone with ideas about decolonising the establishment might need to look away. The floral onslaught is relieved only by Orientalist images of beturbanned individuals, colonial-era scenes and Persian-looking lions. It looks like one of the grand tents the Ottomans used to erect on military campaigns in which to receive guests and diplomats and impress them with their wealth and luxury.

For all the snide tone about John Lewis there is also, oddly, something very English middle-class about it. The yearning for empire, the Chinese porcelain vase made into a lamp, the matching floral fabrics on every available surface — it’s a cocktail of colonialism, misunderstood William Morris, manufactured and manicured eclecticism and fussy fabric. Nabob maximalism.

In her defence, though, Lytle is also a collector of Islamic art and read Egyptology at UCL and this is, after all, her own home.

It is probably not the look for Number 11. The prime minister might worry about a clash with the red wall. Sheer luxury is rarely a good image for a Conservative leader trying to win over Labour voters.

Lytle is also known for rattan, an old craft that has its own colonial veranda implications. She acquired Britain’s last rattan workshop, Angraves in Leicestershire, and is busy reinvigorating the almost lost trade. Lytle owns a rattan piece from the Café Parisien on the Titanic — lightweight, easy to move and rearrange on deck.

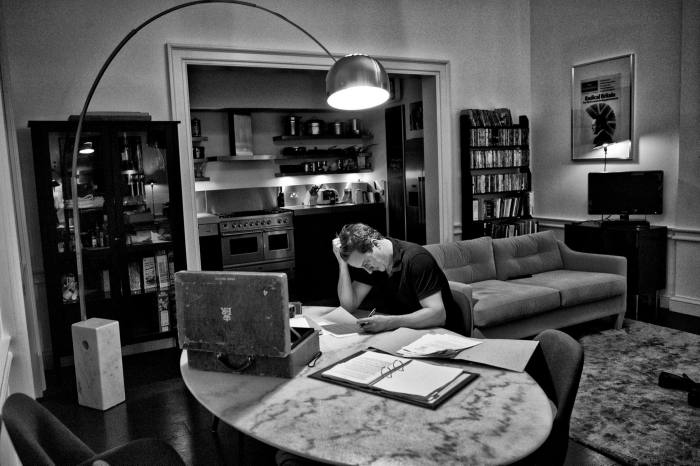

A scroll through the sparse images of previous redesigns of Number 11 takes us on a trip from Cherie Blair’s north London minimalist makeover to Samantha Cameron’s north London minimalist makeover (replete with stainless steel kitchen fittings) via Sarah and Gordon Brown, who apparently did nothing at all. All culminating in Theresa and Philip May’s furniture “nightmareâ€, which seemed to comprise mostly a sofa, a scented candle and a lamp.

Lamps loom large in the archive. In the Cameron era, a Flos Arco-type floor lamp curves overhead, a touch of Italian Modernist glamour. May added a £100 John Lewis table lamp.

Being England, of course, class is at the heart of the furore. Things have changed since Michael Heseltine was dismissed by Alan Clark as the kind of man who had to “buy his own furnitureâ€. Now that “brown furniture†has lost most of its value and status and Victorian seascapes are out in favour of contemporary art, the landscape of inherited artefacts has slid down the scale of class indicators.

We are back in an earlier era of gold wallpaper, exotic artefacts and exclusivity, where expense matters. May’s John Lewis chrome table lamp was not dismissed because it was ugly (although it was ugly) but because it was suburban, accessible and rather cheap. Interior design today revolves around a series of codes, the recognition of rarity, expense and taste. It is the style of top-end country retreats and exclusive members’ clubs.

John Lewis may be aspirational to most of the UK population but for the interiors elite, if you can buy an item on the high street, it lacks that status. Ironically, perhaps, the classiest of all interior styles — the kind of shabby chic that features in the pages of World of Interiors or against which oversized and overpriced Italian sofas are arranged in advertising photoshoots — relies on the survival and preservation of historical finishes, the layering of subsequent redecorations, rather than the obliteration of everything in each incarnation.

And this is, or was, an extremely classy Georgian house in a decent neighbourhood designed, in part, by Britain’s greatest architect. If every PM had just done less, this might have been the most beautiful interior in London.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture and design critic

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

[ad_2]

Source link