[ad_1]

Novelists are already gods of their own fictional realms — powerful creators who can invent entire lives for their subjects, then snuff them out. So it takes serious chutzpah to tinker with another writer’s character, especially if that character is Nick Carraway, the superbly wry, detached narrator of F Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 masterpiece The Great Gatsby.

Michael Farris Smith certainly had the chops to try it. The Mississippi-born writer had five acclaimed novels, including Rivers and The Fighter, to his credit — together with a passion for the murkier decades of American history — before he wrote Nick. Having completed the novel in 2015, he waited for the copyright on Fitzgerald’s book to expire this year before publishing. The result is an ambitious, if not wholly successful, prequel to The Great Gatsby, which attempts to create a wartime history for Jay Gatsby’s Long Island neighbour.

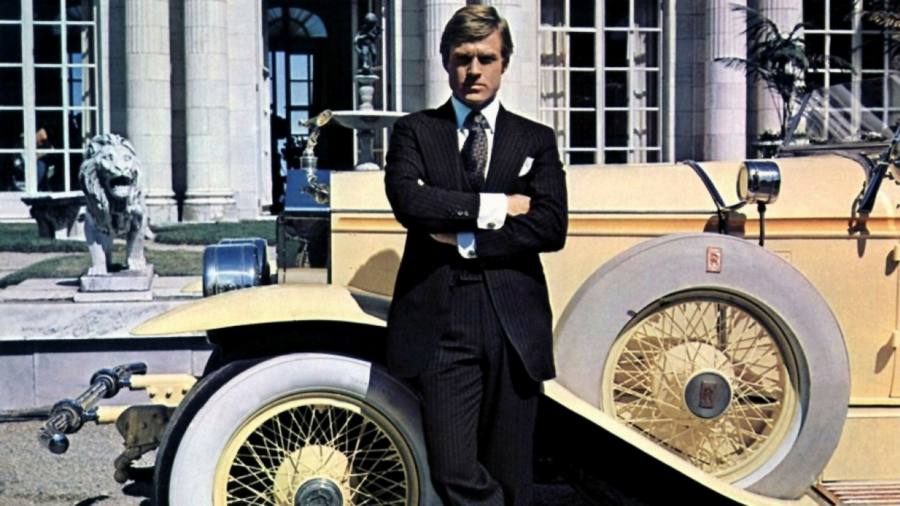

Fitzgerald’s third and most celebrated novel introduces us to the 30-year-old Carraway, a bond salesman living in Long Island after a brief service in the first world war; Gatsby, a self-made millionaire with a murky past; and Gatsby’s old flame, the enchanting but married Daisy Buchanan.

With Nick, Farris Smith gives Carraway a gripping back story, following the character as he explores Paris on brief breaks from the brutality of trench warfare, his cool detachment revealed as acute shell shock. Here, Carraway is already “a watcherâ€, “a listenerâ€, and the Paris sections of his story are dazzling, complete with a sordid love affair with Ella, another lost soul.

But there are times — especially when Carraway’s story shifts to a criminal underworld in New Orleans — when Farris Smith’s hero travels too far from The Great Gatsby, and his laconic cynicism seems more in keeping with one of Hemingway’s characters than Fitzgerald’s milieux.

Most writers are readers first, and many can’t resist the particular challenge of creating something entirely new while staying faithful to another author’s world, tone and character. Fan fiction is already a vast empire, spurring thousands of readers to write spin-offs to classic novels, the majority published on websites that draw masses of followers. Tributes by established authors have also proved popular, from PD James’s Jane Austen-inspired Death Comes to Pemberley, to Sebastian Faulks’s continuation of the James Bond series.

With several other great novels — including Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and Franz Kafka’s The Trial — now finally out of copyright, expect a flood of homages and satires, prequels and sequels. But what determines whether these works actually enhance the pleasure of the original or simply buckle under a weight of self-indulgence?

George MacDonald Fraser memorably took a cowardly, brutish schoolboy bully from Thomas Hughes’s pious 1857 novel Tom Brown’s School Days and created the dazzling and politically incorrect Flashman series. But Susan Hill’s Mrs de Winter, a 1993 sequel to Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, left many of her fans disappointed — it was weak tea to du Maurier’s strong, acid broth. Another middling attempt? Alexander Mollin’s follow-up to Boris Pasternak’s Dr Zhivago: Lara’s Child was too sedate to capture the fire and longing of the original.

A general rule is that the more brilliant the source, the more likely it is an author will fail, however nobly. One notable exception is Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), which reimagined and liberated a minor character in Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre. In Rhys’s unsettling work, Bertha Mason — Brontë’s “madwoman in the attic†— is a Creole heiress named Antoinette.

Confined by her husband, and longing for freedom, she recalls her early life in Jamaica as she lives out her isolated life in an English country mansion. Wide Sargasso Sea stands as a powerful response to Jane Eyre, exploring hidden colonial histories and offering one of the most extraordinary studies of madness and cruelty in literature.

“If there is one thing the lost are able to recognise it is the others who are just as wounded and wandering,†Farris Smith writes in Nick. Read on its own, the novel rings fiercely true; as a Great Gatsby prequel, it falls short. But I understand why Farris Smith tried — that urge to possess and also to transcend a novel is familiar to anyone who’s ever been gripped by great literature. After all, there is no perfect score when you venture into another author’s world — only a thrilling gamble.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

[ad_2]

Source link