[ad_1]

Economic security in old age matters. But it is complex: good policy requires rigorous long-term thinking. Unfortunately, that has been lacking in the UK, which has jumped from one “corner solution†— defined benefit plans — to another — defined contribution plans. The best positions are rarely to be found in corners. It would be better to adopt schemes that pool risks, as DB schemes do, but keep some of the flexibility of DC schemes.

The basic state pension in the UK is extremely modest (a maximum of £179.60 a week). The “gold standard†for pensioners whose earnings make this unacceptably small used to be a defined benefit pension, which promises an income in retirement related to peak earnings. But provision of DB pensions by private corporations has become unacceptably expensive to corporate sponsors. According to the Pension Protection Fund, the number of schemes has duly shrunk from 7,751 in 2006 to 5,327 in 2020; the number of members has shrunk from 14m to 9.9m; only 54 per cent of schemes allow accrual of new benefits by members and only 11 per cent are open to new members. The one healthy part of the DB system is the public sector’s: taxpayers are paying to give public servants an index-linked income-linked pension they cannot have themselves.

Funded DB schemes protect savers against investment and longevity risks by creating a pool of participants whose savings are backed and managed by employers. Unfortunately, private corporations are even more ill-suited to this than they are to providing health insurance: there is a conflict of interest between sponsors and beneficiaries. As scheme collapses made this clear, regulation tightened, making corporate provision of pensions yet more onerous.

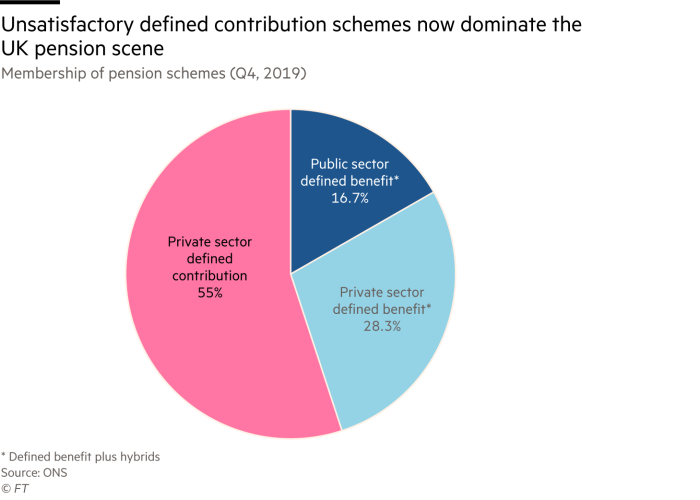

The resulting closures of private sector DB schemes to new members has had a big effect on the pension prospects of most workers. By the end of 2019, 55 per cent of pensioners were in private DC schemes and only 28 per cent in DB schemes. Over time, the latter will dwindle to nothing. The insistence on making pensions ever safer has made pensioners more insecure. (See charts.)

The demand that DB schemes be made as risk-free as possible has also had a dramatic impact on their ability to hold the riskier assets that offer higher long-term returns. This makes meeting pension promises still more expensive. Between 2006 and 2020, the weighted average share of DB portfolios in equities fell from 61 to 20 per cent and the share of UK quoted equities in that total fell from 48 to 13 per cent. So, the latter make up just 3 per cent of DB portfolios.

Michael Tory of Ondra, a boutique investment house, argues that this collapse in the presence of pension funds in UK markets also helps explain the latter’s dismal performance over the past two decades. Between January 2000 and April 2021, the FTSE 100 yielded a total return of just 80 per cent, all of it from dividends, which is the worst performance in all the significant high-income countries.

Yet residual DB assets were still £1.7tn in 2020, which is 85 per cent of gross domestic product. But what new wealth are these funds generating? Desperately little. This is partly the result of all the regulation. It is also because the average scheme has just £319m under management, which is far too small.

Tory makes a radical suggestion: the government should decouple legacy DB funds from their corporate sponsors and consolidate them into, say, four. At the time of consolidation, all contributions including “deficit-reduction contributions†of sponsors should be frozen, thereby releasing them from fresh burdens. The benefits of today’s members would continue to be underpinned by the government, via the Pension Protection Fund, in the event of a sponsor’s failure, as now. Companies would continue to pay the PPF levy. These world-scale funds could, argues Tory, restore UK capital markets to health and help revitalise the economy, especially by investing in infrastructure.

These huge new funds could also be opened to new members from across the country. But benefits to the latter would probably be based on average salaries and, above all, there would be a clear mechanism for adjusting benefits in the light of fund performance. These schemes would not be as generous as the old DB schemes. But they would be far more secure and predictable than today’s risky DC schemes.

The old is dying. But the new is miserable. The country needs large collective funds free not just from the conflicts of interest of old DB schemes, but also from the insecurity of DC schemes. This can be done. But policymakers must first dare to think far more boldly.

[ad_2]

Source link