[ad_1]

Former Merrill Lynch economist David Rosenberg was once a regularly cited entity on these blog pages. It was during the dark days of the Global Financial Crisis, and Rosenberg’s crisp observations about the factors driving the meltdown made him the talk of pundit circles.

Then he joined GluskinSheff where, for a short amount of time, he got even more exposure because his notes became free to read. How we rejoiced. But, alas, soon enough everything became gated. We lost access. Aside from three or four bullet points emailed daily, we were forsaken.

Until . . . January 2020, when Rosenberg launched his own shop, Rosenberg Research. So, every now and then, he blesses us all with a free-to-read sample of his most insightful thoughts.

It’s with that context in mind that his latest landed in our inbox on Monday and piqued our attention immediately.

From Rosenberg (our emphasis):

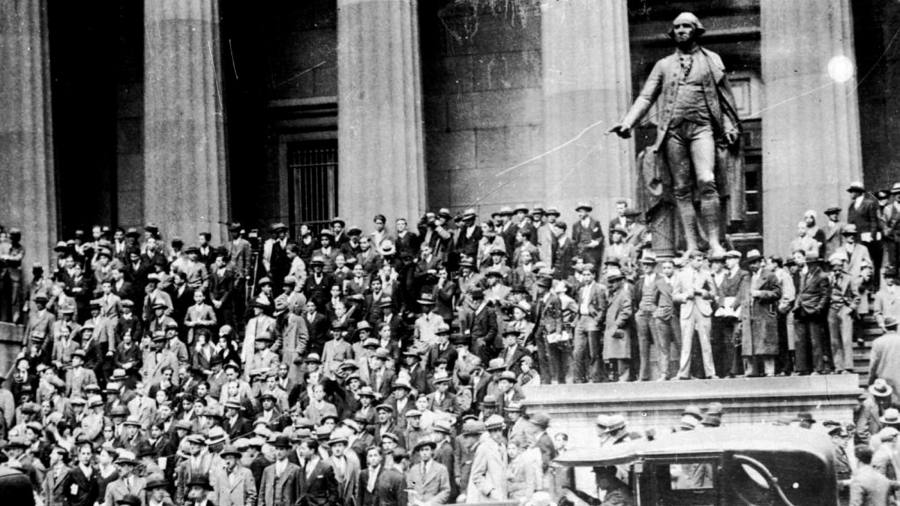

Can you believe we now have three magazine covers talking about the “Roaring Twenties�? I don’t think in my entire career I have seen a fairy tale like this emerge as a given by Wall Street seers and the media

It’s as Wall Street veteran Bob Farrell pointed out, “when all the experts and forecasts agree — something else is going to happenâ€, Rosenberg reminds us.

Rosie, as he is also popularly known, doesn’t buy the comparisons with 1920s largesse nor either with the post-Spanish Flu period in general.

This time is different because there is no prospect, in his opinion, of a global boom once we get past the pandemic due to the scale of the debt already in the system.

Here’s the gist of Rosenberg’s rationale (his emphasis):

For one, coming out of WWI, which was ending as the Spanish flu was starting, the US had come to account for half of global manufacturing production. That’s because the war savaged the entire European economy and gave US industry the opportunity to grab global market share in exports and industrial production.

Second, the US dealt with the Spanish flu totally differently. The economy never went into full lockdown. People just learned to live with the disease, which ultimately vanished on herd immunity. Back then, nobody turned to the government for help; it was all about community and charity. These were the days before welfare and unemployment insurance benefits and company bailouts. Public attitudes toward illness and death were far different and there was no internet or social media to try and influence people’s perceptions and stir up emotions.

The economy did collapse back then, but the government did not blow its brains out on fiscal largesse. So, we went into the 1920s with tremendous pent-up demand once the crisis ended, and balance sheets were in far greater shape. Government debt-to-GDP was 10 per cent — not over 100%. And that better public sector balance sheet allowed the federal government to CUT taxes by the mid-1920s — top marginal rates for corporations were initially raised from 10 per cent in 1920 to 13.5 per cent by 1926 but cut to 11 per cent by the end of the decade; for individuals, the rate went from 58 per cent after the war to 24 per cent by 1929. Does anyone think taxes are going to be coming down in the US any time soon?

The above, he reminds us, also comes in the context of de-urbanisation and a static home ownership metric rather than the growing urbanisation and increasing home ownership trend of the 1920s. This is important because urbanisation is a critical stimulus for any economy.

The other big difference is the share of “essential†economic activity that could not be closed down relative to “non-essential†activity in the 1920s was a massive 90 per cent. Today essential activity represents less than 30 per cent, meaning the economy isn’t as geared towards powerful multiplier impacts through the rest of the economy.

Last off, there are the demographics. The share of the population over 65 in the 1920s was a humble 7 per cent in the US, compared to 20 per cent today. That matters because elders don’t spend as much as younger people.

So in summary, Rosenberg just doesn’t see the maths working out to prompt the massive inflation everyone is worried about. Above all, today’s corporate mindset is all wrong, not least because it’s far more skewed towards financial engineering than growing the capital stock as it was in the 1920s.

As for the stock market:

. . . indeed, it did rally 250% from the beginning of 1920 to the pre-crash 1929 peak. But the starting point on the CAPE multiple then was below 6x, not at 35x! Even adjusting for interest rates, the stock market today is two-and-a-half times more expensive than it was when the “Roaring Twenties†began. So not only is the outlook for demographic support, productivity, debts and taxation so vastly different, but so is the starting point on valuations for the stock market.

So chew on that.

Related links:

Man Group’s Draaisma notes inflation paradigm shift is possible — FT Alphaville

No, inflation isn’t back — FT Alphaville

[ad_2]

Source link