[ad_1]

Who are the final winners from the Robinhood saga? If you ask Reddit-reading retail investors, they might mutter angrily about Wall Street banks and hedge funds such as Citadel.

Fair enough. Some hedge funds, such as Melvin Capital, were damaged by last week’s market mayhem. But other established traders profited handsomely, such as market makers.Â

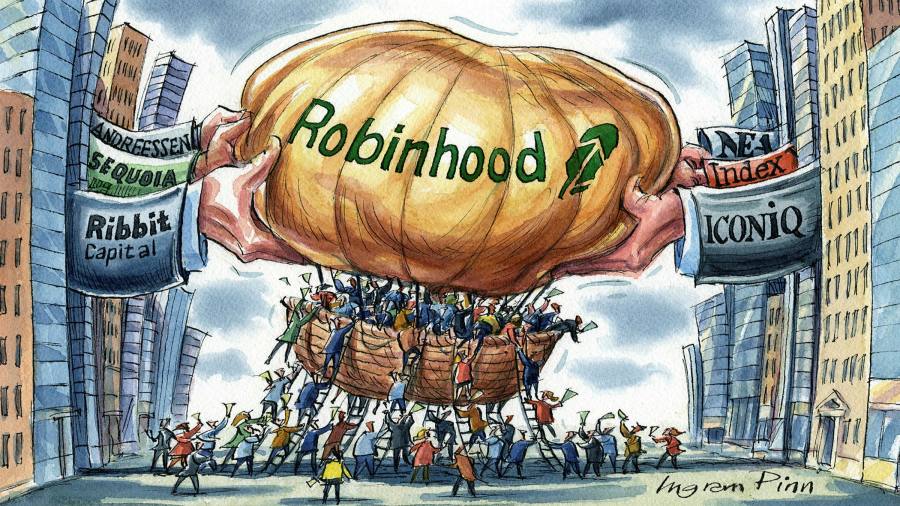

However, I suspect that if you review events in a year’s time, there may well be a set of bigger winners: the consortium that has pumped $3.4bn into Robinhood to shore up the broker.Â

This financial lifeline, which appeared as fast as the rise and fall of GameStop shares, was led by Ribbit, a little-known Silicon Valley venture capital firm that seeded Robinhood, along with better-known VC giants such as Sequoia and Andreessen Horowitz.

The consortium also included Iconiq Capital, a discreet family office that reportedly manages the wealth of tech titans such as Mark Zuckerberg, Reid Hoffman and Chris Larsen. Moreover, the group cut a deal that could turn its original investment into tens of billions of future equity, if a public offering occurs (one was planned for this year).Â

Although this deal received relatively scant public attention, it is striking for two reasons.

First, the $3.4bn infusion shows that the smart inside money in Silicon Valley sees a vibrant future — and rising value — for Robinhood, whatever may happen at Washington’s looming regulatory debate and hearings.Â

That prospect may horrify financial traditionalists, who hate how Robinhood presents investing as something akin to a video game. It may also upset those politicians who fear the app is simply the latest tool that enables Wall Street to fleece the public. Whatever the case, the funding round is a warning to these established players that the idea behind the app is unlikely to disappear.

The second important point is that the saga demonstrates the muscle of private pools of capital generally, and of family offices in particular. Tracking the latter is notoriously hard: the family office sector is so obsessively secretive that reliable statistics are sparse. The decade-old Iconiq Capital, for example, long lacked a website (its current, cursory one shows that it commands a formidable $54bn of assets.

Even so, in 2019, financial consultants Campden Wealth declared there were 7,300 single family offices in the world, 38 per cent more than in 2017, controlling almost $6tn. This may well eclipse the hedge fund sector, which is thought to control $5tn, according to the US office for financial reporting — although there may be some double counting here, as family offices give mandates to hedge funds.

As notable as scale, though, is the shift in investment style. The family offices that first emerged in places such as Switzerland to manage European old wealth were as staid as their clients. But their newish counterparts, such as Iconiq, serve 21st century tycoons who made their money more recently by embracing risk, long-term horizons and rapid decision-making.

Such features are increasingly embedded in investing styles too, since family offices now make direct investments into ventures, often alongside the VC funds they used to contract to do that. A recent Campden survey of 130 family offices found that 10 per cent of their assets sit in VCs, mostly via direct investments. Average internal rates of return were 14 per cent last year, and 17 per cent for direct deals.

The returns for groups such as Iconiq are almost certainly far higher. The group has backed ventures such as Snowflake, Airbnb and Zoom, as well as fast-growing sectors such as data centres. Making a virtue of being a multi- and not a single family office, it also prides itself on both its ability to leverage financial firepower as well as its clients’ collective brains and networks.

This family office trend will probably worry anyone concerned about income inequality, or the disparities between the investment returns delivered by mass-market pension funds versus the smart ultra-rich money that backs groups such as Iconiq. As the celebrated economist Thomas Piketty argued, invested wealth begets more wealth.

However, while such disparities seem distasteful, if not immoral, the presence of such pools of capital can also be beneficial — at least from a narrow, if amoral, capital markets perspective. Public markets are currently dominated by passive herd-following investment funds and active investors with a short-term focus such as Robinhood-style day traders.

Family offices, by contrast, provide patient, risk-seeking capital. This, as their managers stress, enables them to fund the type of innovation and corporate activity that the world needs to create growth. Their speedy decision-making skills and deep pockets also mean that they can, on occasion, stabilise markets, pace last week’s events.

This will almost certainly not appease the rebellious Reddit-reading investment crowd. In a more perfect world, it would also be mass-market pension funds that provided such patient capital and, crucially, reaped its fat returns.

Meanwhile, in the current world, the irony is inescapable. Robinhood’s marketing pitch is to democratise finance by giving punters easy access to public markets. Yet that is not where the lucrative action is.Â

[ad_2]

Source link