[ad_1]

The writer, Nikkei Asia’s editor-at-large, is a senior fellow at Chulalongkorn University’s Institute of Security and International Studies

There is nothing like persecution to restore a tarnished reputation. Such is the case of Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s state counsellor and de facto leader. Only a few weeks ago, the former political prisoner and Nobel laureate was being vilified internationally for defending Myanmar’s military against accusations of genocide. On Monday, after her arrest and the military overthrow of her government, she became a martyr again.

It was a staccato coup. Parliament was closed, MPs detained and legislative, judicial and executive powers given to the military’s commander-in-chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The official reason for her arrest is illegally imported walkie talkies. But the motivations behind the putsch are festering resentments catalysed by last November’s election, when Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party won a landslide popular vote.

That she ignored the generals’ complaints, however unfounded, proved a grave political mistake. It may have been out of arrogance, hubris over the size of her electoral win, or the fact she defended the military’s brutal expulsion of Rohingya muslims in 2017 and felt no need to pay the military more attention. Either way, western governments and organisations, having spent years condemning her, now find themselves calling for her unconditional release.

The coup brings home what her supporters fervently believe: without “the Lady†at the helm, the military will take Myanmar back to the dark ages. Her predecessor, President Thein Sein, kickstarted economic reforms in 2011. But it was only after her accession to power in 2015 that US president Barack Obama heeded her requests to lift sanctions. Her lofty status was why so many other countries poured aid and investment into Myanmar.

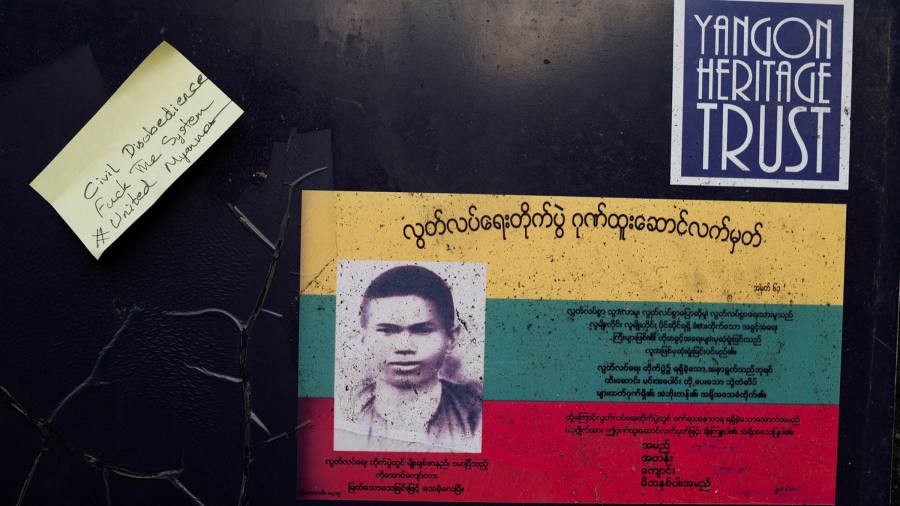

At home, she retains astonishing pulling power. Her call this week for supporters to resist and protest has ignited a campaign of civil disobedience. Aung San Suu Kyi has been here before, as it was the suppression of the “8888†uprising on 8 August 1988 that brought her to prominence. This time, though, Myanmar’s predominately young population is more sophisticated, more angry and more determined. A bloodbath is possible.

That is another reason why the international response needs to be carefully calibrated. The country is a “tinderbox that could explode like a nuclear bombâ€, a seasoned observer in Yangoon notes.

Medics have quit their jobs at state hospitals, saying they refuse to work for an “illicit governmentâ€. Some civil servants have said that they cannot work for the junta. And Yangoon resounds nightly with the roar of clanging metal as people bang pots in protest.

Meanwhile, the generals are continuing to arrest activists and civil leaders. Internationally, US president Joe Biden, under pressure to make good on his pledge to restore faith in America’s democratic principles, has made it clear that sanctions are on the table. The EU is weighing similar actions.

This is history repeating in Myanmar. Swingeing sanctions from the late 1990s destroyed livelihoods and devastated an already failing economy. Other financial curbs hit businesses and deterred foreign investment, tourism and commerce. At least this time there is talk of targeted sanctions aimed at military-linked enterprises. But in an economy where the military is so deeply entrenched, the line between such businesses and rest is blurred.

What next? Western officials fear pushing Myanmar further into the arms of China, which consistently rejects attempts by the UN Security Council to place sanctions on the country. But the junta, with its pariah status renewed, has few apparent alternatives. Reversal of the coup seems highly unlikely. Although fresh elections have been promised, the military has broken its pledges before.

Even so, for concerned governments, negotiation and mediation should be the next steps. That Gen Min Aung Hlaing has been sanctioned for his role in the Rohingya pogrom makes this harder still. But there are potential channels. Japan, eager for a leading role in the Asia-Pacific, has invested in Myanmar and built strong relationships with the military. Another channel is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Liaising with the junta will be distasteful. But time is short. Civil disobedience is gaining momentum and the military is as ruthless as ever. Rather than stand aside, the first aims of the international community should be to deflect violence and seek the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and other detainees. These are the bare prerequisites for broader progress.

[ad_2]

Source link