[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Summer really feels like it’s here, and I feel great. I must be missing something. Email me if you know what it is: robert.armstrong@ft.comÂ

Shocked by the obvious

The market threw some of its toys out of the pram last week. Let’s review.

The yield curve went dramatically flatter as the market adjusted to the Fed’s new rate stance (all the data that follows is from Bloomberg):

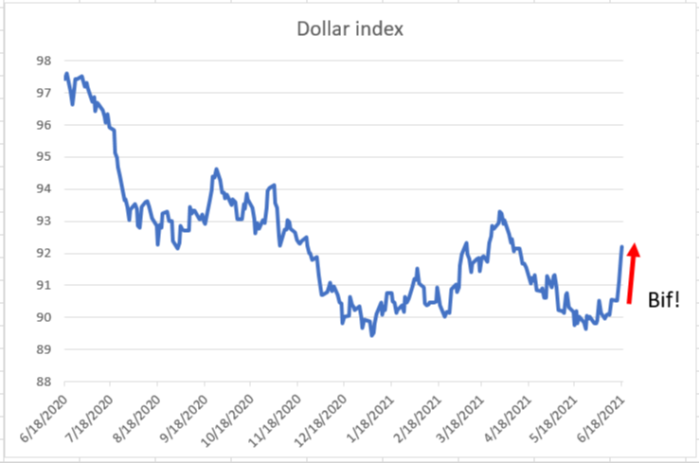

The dollar spiked in anticipation of higher short-term interest rates:

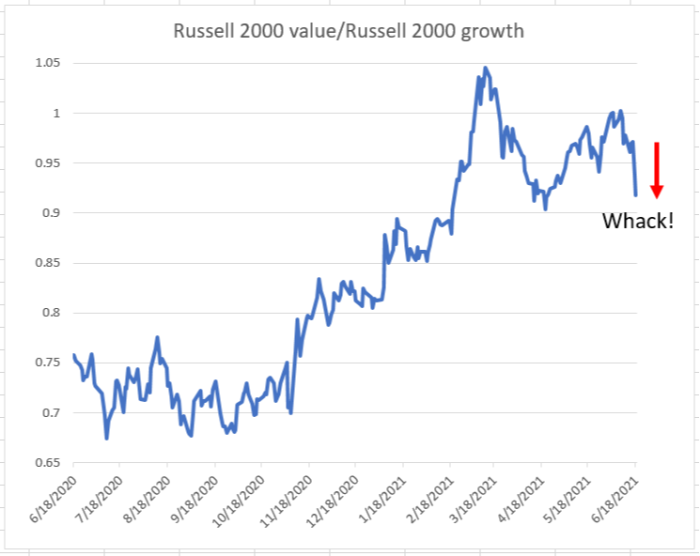

Investors abandoned the reflation trade, dumping cyclical value stocks in favour of growth stocks expected to stand out in a lower-growth world:

Stocks generally took a few lumps, as well. As the market moved, the consensus quickly formed that the Fed had sprung a “hawkish surprise†on Wednesday. The story went like this: after months of talking about its new inflation-targeting regime, and how it would tolerate inflation running above its target for a while, the Fed’s dot plot showed that the Open Market Committee members were much more hawkish than they had let on.

The dot plot that stimulated this bitter sense of betrayal showed the following:

-

Seven of the 18 members see a rate increase in 2022, versus four before;

-

Thirteen members see at least one rate increase in 2023, versus seven before; the average member expects two hikes, to between 0.5 and 0.75 per cent.

I talked to Rick Rieder about the market’s response. As BlackRock’s fixed income CIO, he is responsible for something approaching $2tn in bond portfolios. He described the market’s shock and mad rush to adapt:

There was this extraordinary surprise, in terms of the Fed moving as much as they did, because it was completely different than what they had said to date. The way those dots moved forward . . . you have to think the leadership is comfortable tightening sooner.

It was as large as a technical unwind of positions as I have seen — an extraordinary cleansing.

He described a situation where almost everyone was on one side of the steepening curve trade and other trades connected to it:

The liquidity of the markets was very thin. Often when people look at volumes being high, they think there is a lot of liquidity, but at any given price, liquidity was very shallow. Every time something was done it moved the market. Nobody wanted to be on the other side of these trades.

There was such a crowding into the same positioning, that this massive unwind followed . . . in a world where you have so much social media and everything else, everyone can line up on one side and when something changes, it can really upset the apple cart.

He does not think the Fed is making a mistake, though: “it’s totally appropriate, I think the Fed is doing the right thing.†This sums up the situation perfectly. The Fed said some things. The market, caught badly off side and piled into a consensus trade, freaked out. But the Fed said what needed to be said.Â

What’s more — and here I disagree with Rieder — given what the Fed had said in the past and what had transpired in the past few months, what the Fed said should have been totally unsurprising.Â

The Fed kept policy where it was, as expected. The chair said plainly that the committee as a whole expects inflation to be transitory, and as such sees no present need even to discuss raising rates, but that optimism about employment coming back means that, at some point later, discussing tapering asset purchases will make sense. This is mild, mild stuff, given that the past two core CPI prints were 3 and 3.8 per cent.

As for those dots, they delivered the shocking news that, with CPI, wages, employment, commodities, housing, and about six other things heating up, maybe rates will have to be nudged up a tiny bit a year or more from now, and maybe nudged a bit more within the next two and a half years. Friends, that’s what higher tolerance for inflation running above target looks like.Â

A market that is surprised by this, given what the Fed has said and the data it is seeing, is a market that has lost touch with reality. It wanted the growth and the inflation and the sky-high asset values and the near-zero short-term rates and they wanted it all for ever and ever. And when Santa didn’t deliver all of that, and a pony too, it panicked.

The distinction between a market that panics because the Fed changed its stance and a market that was brought back to reality by the Fed acting reasonably is important. If you believe we just saw the former, you might hope in the future that some better calibrated, more precisely telegraphed action from the Fed will keep the market tranquil. But this will never happen, because a market that is huffing the glue of euphoria cannot be pleased. If we are going back to anything resembling normal policy, the Fed is going to drag the market there one messy overreaction to obvious facts at a time.

Of course you can argue that it is hard to come back neatly from very easy monetary policy, and that proves that the Fed’s whole approach is wrong. Or you can argue that the dot plot is a mistake, or that the Fed’s policy should be driven by mechanical rules instead of judgment. All of that may be true.

But if you think the Fed has just made a tactical or operational mistake, as opposed to being strategically or philosophically misguided from the outset, all that shows is that you are huffing the same glue as everyone else.Â

One good readÂ

Late last week the WSJ had a very nice review of the effects of retail traders — now accounting for 20 per cent or more of volumes — on US stock markets. This stuff is no joke.

[ad_2]

Source link