[ad_1]

On Sunday, Mario Cibelli, a founder and portfolio manager at US-based investment firm Marathon Equity Partners, posted a Twitter thread on what negative feedback investors might encounter when faced with a scaling, and ultimately successful, consumer business.

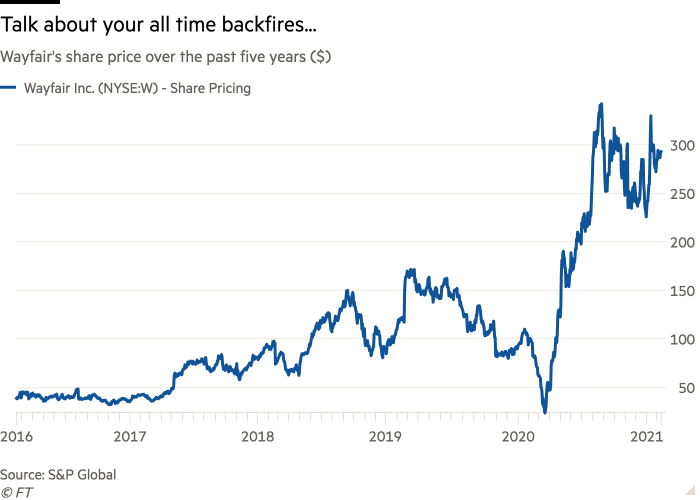

Reading through it, FT Alphaville had a sudden painful pang as we remembered our articles on $29bn online furniture retailer Wayfair from a few years back. Not just because we ended up being horribly wrong on the stock, but also because the reasons we were wrong were perfectly outlined by Mr Cibelli.

Our argument against Wayfair’s then exuberant valuation were multi-faceted, but can be boiled down to three connected points.

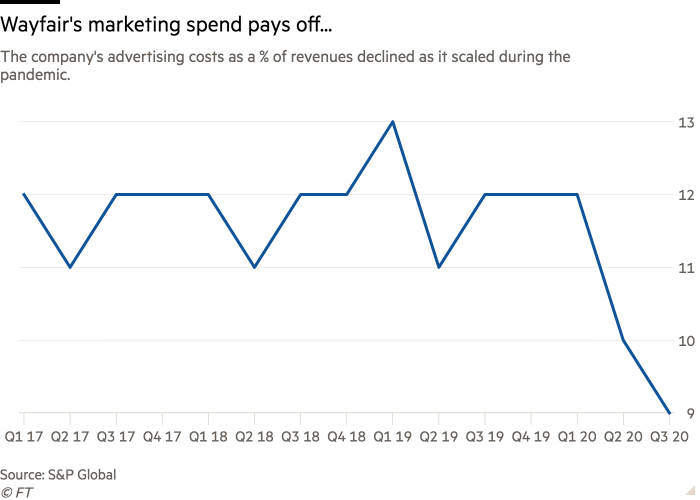

First is that the business had struggled to demonstrate that it could control marketing costs in years of strong revenue growth, meaning it often missed its own profit margin targets. To us, this showed Wayfair was facing competitive pressure and was therefore overpaying to bring in new customers. In the longer term, we thought this would weigh on its bottom line.

Second was the fact that furniture is particularly difficult to sell online due to its relatively high price points, supply chain complexity and return costs. This meant, versus say Amazon, generating a negative working capital cycle from high volumes would be trickier than traditional ecommerce. Higher return costs would potentially also mean structurally lower profits.

Third was that furniture purchases were often one-offs, while the company liked to frame its relationship with its customer base as a quasi-recurring one, perhaps in a bid to gain more of a software like valuation for its stock.

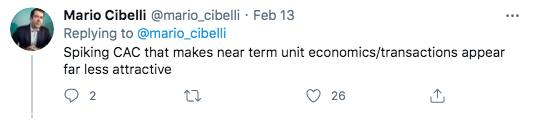

Yet reading over Mr Cibelli’s arguments, we saw the errors in our thinking. In particular, this point he made in the second tweet of the thread:

In non-finance bro parlance, “spiking CAC†is short for “high costs to attract customers†(CAC stands for customer acquisition cost).

This, as we explained above, is what we saw at Wayfair — its marketing spend was attracting less and less customers as it spent more. However, there’s another way to think about this which we ignored at the time: by overpaying for customers in the short term, you’re maximising the chance they return to your platform to buy again in the longer term. Even, and this is the crucial point, if the goods are available elsewhere.

Think about it, once you’ve purchased batteries on Amazon once — are you really going to shop around the next time for a better price? Or are just going to go down the tried and tested route because it worked before? Granted, buying a chair, table or light fitting is a different type of purchasing decision to say, a box of matches, but if Wayfair was competitive on price last time, why would it be any different now? Therefore, by seemingly overspending on customers now, Wayfair is guaranteeing at least a higher degree of loyalty from them later. This was particularly crucial in an industry where the competition was, at the time, lagging the company’s efforts.

This feeds into the second argument we made — that furniture, due to the size of the items, the difficulty in returning them, and the relative lack of repeat orders, meant it simply was a much harder type of product to sell online. Yet what we didn’t consider that this was also a positive for Wayfair. By gaining a deep expertise in a type of good with idiosyncratic selling, delivery and return requirements, competitors would find it much harder to enter the space without sustaining large upfront losses. It also meant that any cost efficiencies Wayfair gainted it could immediately pass onto customers, only deepening its competitive position further.

Together, both of these arguments refute our third bearish take: that furniture purchases are relatively non-recurring. This doesn’t matter so much if your platform becomes the go-to place to buy everything from carpets to door knobs to dining chairs.

Now, of course, there’s an elephant in the room here: with people both stuck at home due to the coronavirus pandemic and not spending money, home improvements became one of the few places people could spend their cash. For Wayfair, it’s been a total boon. In the second quarter of 2020, its revenues grew at astonishing 85 per cent quarter-on-quarter as workers decided to deck out their home offices, living rooms and gardens. This time however, costs didn’t follow, with Wayfair’s ebitda margin rising to 1 per cent in the 12 months through to September 2020, versus minus 9 per cent in 2019.

Yet for FT Alphaville to simply say “we were right until the pandemic†ignores two key points. First, Wayfair would not have been the go-to platform for furniture if it had not run its market spend hot in the years up to the pandemic. Second, it wouldn’t have been able to smoothly meet this sudden surge in demand without the logistical muscle-memory built up from previous investments in capacity and its supply chain. In other words, a lack of profit before coronavirus allowed it to become profitable during it.

All of this looks obvious after the fact, and whether Wayfair would have ever reached the scale it has now without the virus is impossible to prove. But when you’re wrong, it’s best to figure out why.

Wayfair was nuts, but it’s not anymore.

Related Links:

Wayfair is nuts, when’s the crash? — FT Alphaville

Wayfair: mo growth mo problems — FT Alphaville

Mario Cibelli – Cornerstone Investing Insight‪s — Invest Like The Best [podcast]

[ad_2]

Source link