[ad_1]

Wrinkles and grey hairs notwithstanding, I must be younger than IÂ had assumed. Sixty per cent of the adult population of the UK have been vaccinated with at least one dose, but your columnist is not old enough to be one of them. Who knew?

This means I still have the joys of a jab ahead of me, and I can’t wait for the sweet superpower of immunity. All the available vaccines in the UK are hugely effective at preventing severe illness, and they increasingly look as though they greatly reduce transmission too.

And yet, when the needle finally slides into my arm, I’ll have to suppress a nervous gulp. The AstraZeneca vaccine I am likely to receive, developed in my home city of Oxford, has rarely been out of the headlines — most recently because of the suspicion that it may make a rare form of blood clot slightly less rare. The same suspicion has led US authorities to recommend suspension of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine.

Our gut feelings are powerful. The AlpspiX viewing platform in Bavaria is a cantilevered structure, where a mesh floor reveals an unnervingly large drop. My rational mind tells me it is perfectly safe. My legs and my stomach tell me something else entirely; I find it hard to physically make myself walk out to the end.

The philosopher Tamar Gendler coined the word “aliefâ€, a counterpoint to “beliefâ€, to describe such instincts. I believe the AlpspiX platform is safe; I “alieve†that it is extremely perilous.

And the vaccine? Setting “alief†to one side, I believe it is extremely safe. The clotting side‑effect of the vaccine is rare — so rare that we are still not certain that it exists. It is certainly far too rare to discover in a controlled clinical trial, where a vaccine dose is given to tens of thousands of participants rather than millions.

An educated guess, based on UK data, is that being vaccinated with the AstraZeneca jab carries a one-off risk of death of one in a million — not much higher than the risk of dying in an accident while travelling to a vaccination clinic. If that guess is correct, vaccinating the entire UK population with a dose of this particular vaccine would give 67 people fatal blood clots.

That sounds bad — as does any sentence containing the phrase “fatal blood clotsâ€. Yet in the UK the death toll from coronavirus was never below 67 per day between mid‑October and late March — and sometimes headed for 67 per hour. In other words, for the entire winter wave, a single day’s delay to being vaccinated has been riskier than the vaccine itself.

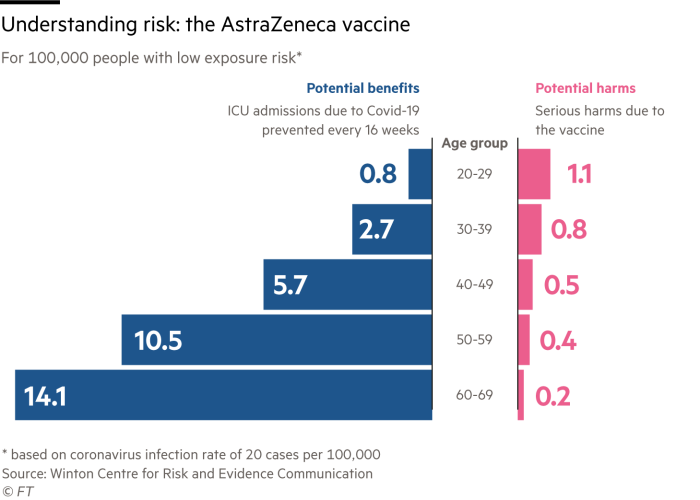

Individual risks vary: young people are at vastly less risk of a fatal dose of Covid-19 and perhaps at somewhat higher risk of vaccine side-effects. Researchers at the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication have put together an excellent visualisation of the estimated risks, showing that for most people, in most circumstances, the vaccine prevents much more harm than it might cause.

But for young people, during a lull in the pandemic, the balance of risks is less clear cut, which is why the British authorities are planning a brief delay to ensure young people receive a different vaccine.

The numbers should be very reassuring. But our emotions do not always respond to numbers. David Ropeik, author of How Risky Is It, Really?, points to a variety of factors that make some risks loom large in the imagination.

The most obvious is salience: in recent weeks, particularly in the UK and EU, there has been saturation coverage of the blood‑clot story, despite the fact that by any measure there have been vastly more deaths from Covid-19 itself. This is understandable — news is news, after all — but it leads our instincts astray. The rational question is, “Statistically speaking, do the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the harms?â€, but the easier question is, “Can I easily call those dangers to mind?â€

A second factor is control. Driving is more dangerous than flying, but most people fear flying more: they feel they can protect themselves while driving, but not while flying. To an extent, that is true — and also true for Covid-19. There are steps we can all take to reduce the risk of infection, and there is nothing we can do to reduce the risk of a fatal reaction to a vaccine. The fact remains, however, that planes and Covid-19 vaccines are very safe — and cars and Covid-19 infections are not.

A third factor is trust. I know about Boris Johnson’s track record with truth, and am far from reassured whenever I hear him declare his confidence in the AstraZeneca vaccine.

Scientists, fortunately, remain more widely trusted. Professor Sir David Spiegelhalter of the Winton Centre tells me that the announcement last week was a “tour de force of risk communicationâ€, largely because the politicians were nowhere to be seen. Instead, scientists and medical officials presented risks and benefits in a sober way, doing a lot to earn the trust of viewers. That counts for a great deal. Ultimately, our view of vaccines depends not on the data, but on something more primal: do I trust these people to have my best interests at heart?

The data tell me that the vaccine is not only safe but a life saver for me and for those around me. I’ll still be nervous when I finally get to the clinic, but I can’t imagine it will be nearly as bad as the AlpspiX platform. And if I had to walk out on that platform to save a life? I wouldn’t like it, but I’d do it in a heartbeat.

Tim Harford’s new book is “How to Make the World Add Upâ€(UK)/“The Data Detective†(US)

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first.

[ad_2]

Source link