[ad_1]

This is the second in a series on Joe Biden’s first 100 days in office

If Joe Biden’s first 100 days had ended after 85 days, his Covid-19 vaccine rollout would have been an unqualified success.

Early in his presidency, Biden made a series of changes to the plan he inherited from the Trump administration, including setting up federally managed mass vaccination sites and deploying armed forces personnel to assist with managing them. That push helped his administration hit its target of administering 200m doses on April 21.

But a week before that milestone was passed, a problem began to emerge as the pace of vaccinations dropped and the stockpile of unused vaccinations increased. The sudden slowdown has exposed Biden’s next two big challenges: persuading reluctant Americans to take the jabs that are now available, and making sure the rest of the world does not go without.

“They got off to a fantastic start,†said Dr Tom Frieden, a former director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “They made sure it was clear who was in charge of what, and they started communicating openly and clearly with Americans about what was happening. None of those things had been done before.â€

Frieden added: “Now, however, you’ve got a slowdown in vaccinations. That’s because you’ve gone from getting the most eager people vaccinated, to reaching the ‘moveable middle’ [of people who are less sure about getting vaccinated], and in some cases, the immovable end.â€

The US vaccination rollout has been the largest in the world, with 232m doses administered — enough to give just over half the adult population at least one dose. After a slow first few weeks last year, it has now caught up with the UK in terms of the number of doses administered per capita, and is ahead when measured by the proportion of people fully vaccinated.

Biden officials have been keen to take credit for the rollout, with the president on Tuesday celebrating his administration’s “stunning successâ€.

But others point out that the foundations were laid during the Trump administration, which launched Operation Warp Speed, the $10bn government investment programme to fund Covid vaccines and treatments.

Under that scheme, the Trump administration signed pre-orders for 800m doses from six companies, allowing them to conduct trials and expand manufacturing with almost no financial risk.

A batch of mRNA vaccines such as those made by Pfizer and Moderna takes nearly three months to make and test, meaning almost all of the doses administered under the Biden administration began production under former president Donald Trump.

“It’s a bit infuriating when they take credit for everything,†said Paul Mango, who was deputy chief of staff at the health department in the previous administration. “They have stayed out of the way and nature has taken its course.â€

Most experts, however, say the Biden administration made two big changes which helped make sure those finished doses were used quickly. The first was to guarantee a minimum number of doses to states three weeks in advance, ensuring governors and health officials could put the right people and resources in place to administer them.

The other was giving states more money and manpower to set up locations, and even using the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which handles disaster response, to establish its own mass vaccination sites.

The combination of extra certainty and extra resources has enabled the US to steadily increase the pace of vaccinations, which hit a daily average of 3.4m earlier this month, according to data from Bloomberg.

Recently, however, the pace has slowed to an average of 2.7m a day, something experts blame in part on a reluctance or inability of millions of Americans to get vaccinated quickly.

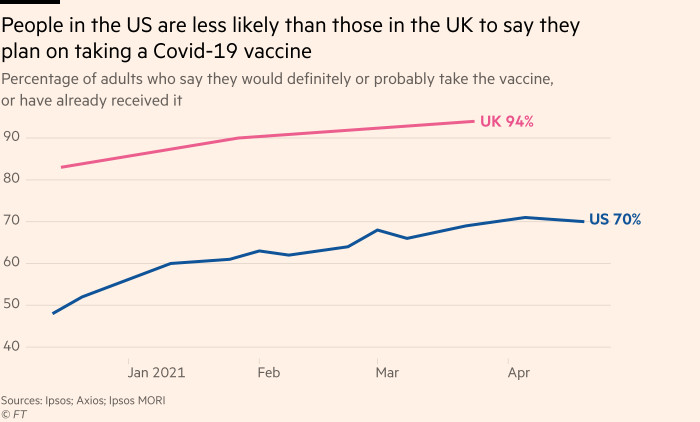

According to polling by Ipsos Mori, 70 per cent of Americans say they have either been vaccinated or will definitely or probably do so. That compares with 94 per cent in the UK.

The difference in attitudes helps explain why only 81 per cent of over-75s have been vaccinated in the US despite the wide availability of doses, compared with 98 per cent in England.

Liz Hamel, director of public opinion research at the Kaiser Family Foundation think-tank, said: “What we’ve been seeing over time is people who said they wanted to ‘wait and see’ before getting a vaccination decide they want to do so ‘as soon as possible’. But we’re starting to run out of people in both of those groups, and into the group who definitely do not want to get vaccinated.â€

The KFF’s research suggests about 20 per cent of people either say they will not get a vaccine, or will only do so if mandated, a figure that has barely changed since December.

Problematically for Biden, this group is overwhelmingly made up of people who did not vote for him. The KFF has found that 65 per cent of them are Republican and 43 per cent are evangelical Christians.

Others say they would like to get a vaccine but have found it difficult to find time to do so. Biden has responded by calling on employers to provide paid leave for vaccinations and offered a tax credit to small- and medium-sized businesses to help them pay for this. But the White House has ruled out stronger action which might be seen as coercive, such as developing a government-run vaccine passport scheme to grant vaccinated people additional freedoms.

“I think we are going to need mandates, whether it is mandates for children or mandates for healthcare workers,†said Dr Zeke Emanuel, a professor of healthcare management at the University of Pennsylvania and a former coronavirus adviser to Biden. “I would like employers to think deeply about mandating their workers to get vaccinated.â€

Meanwhile, the glut of doses in parts of the US has renewed calls for Biden to do more to increase access elsewhere in the world, especially in India, which is suffering a disastrous second wave of infections.

The administration has said it planned to export up to 60m doses of AstraZeneca’s vaccine, which has not yet been approved in the US, to countries including India. But it is also under pressure to do more, whether by forcing pharmaceutical companies to waive intellectual property protections abroad or by incentivising them to set up manufacturing plants in other countries.

“If we have any spare capacity we need to use that for the rest of the world,†said Emanuel. “We should help with capacity, knowhow, sending vaccines overseas. We are in a situation of oversupply for Pfizer and Moderna doses; other parts of the world need those vaccines.â€

[ad_2]

Source link