[ad_1]

When Joe Biden next week inhales the Atlantic air as he walks down the steps of Air Force One on his first overseas trip as US president, he will become the latest visitor to a jagged peninsula at the south-western tip of the British mainland that is already full: Cornwall.

This corner of the UK barely needs any more publicity. It was already one of the UK’s most popular domestic holiday destinations, and the continued pandemic restrictions on foreign travel has ensured that hotels and restaurants are packed.

The arrival of Biden and other foreign leaders for the G7 summit, which starts next Friday at a boutique hotel at Carbis Bay, will only reinforce the region’s reputation as a premium destination.

A wedge of granite jutting out into the Atlantic, the allure of the Celtic region is built on myths and legends. The G7 will add another layer to Cornish folklore as the world’s leaders gather to try to sort out the world’s problems.

Already tales are circulating of how Biden’s entourage will have to swap his armoured Beast limousine for a “mini-Beastâ€, better suited to Cornwall’s narrow, twisting lanes.

Local police are concerned that the area’s notoriously aggressive seagulls could damage the drones providing surveillance for the huge security operation.

Cornwall provides a backdrop in miniature of some of the main themes that will dominate the summit.

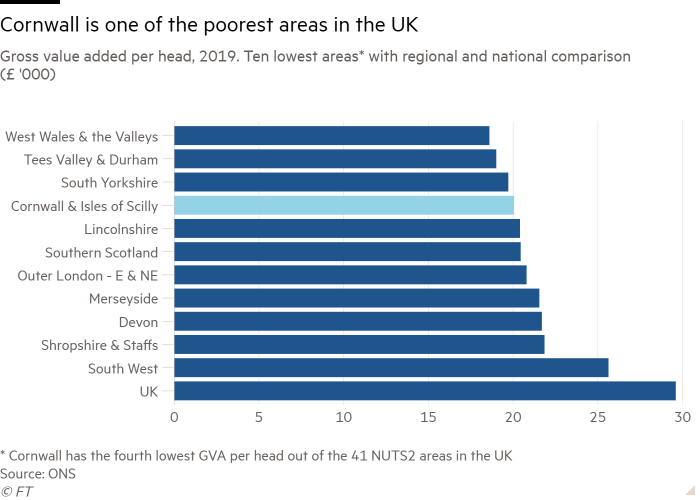

Climate change: the county has geothermal power. Industries of the future: UK prime minister Boris Johnson has dubbed the county the “Klondike of lithiumâ€. Inequality: there are plenty of examples of poverty in Cornwall and it is one of the regions targeted in Johnson’s post-Brexit “levelling up†agenda.

The G7 summit will highlight the disconnect between the kind of people who stay in the Carbis Bay hotel — and the multimillion-pound houses strung out along the stunning Cornish coast — and those living elsewhere in one of the poorest parts of Britain.

Locals, who often work in low-paid hospitality jobs and face steepling housing costs, have little hope that a brief visit from Biden and the other world leaders will do much to change their lot.

A 10-mile drive from Carbis Bay, on the Pengegon estate in Camborne — officially one of England’s most deprived neighbourhoods — the residents were unimpressed by the arrival of the G7 diplomatic circus. They complained that world leaders are able to fly into Cornwall in a pandemic, yet they were unable to see loved ones for months.

“They are famous people. There seems to be one rule for them and another for us,†said Heidi Chesterfield, a carer. Her friend, Anna Francis, is sceptical that the county will reap long-term benefits from hosting the summit. “Cornwall is the end of the line — we are always forgotten.â€

Downing Street has tried to embrace this awkward juxtaposition of wealth and poverty. Johnson will claim that the G7’s agenda of green growth and new technology will precisely benefit remote regions such as Cornwall, with its aspirations as a leader in renewable energy, green tourism and even space — the county has plans to build the UK’s first space port.

But some are sceptical. The resentment towards a distant EU elite that manifested itself in Cornwall’s pro-Brexit vote in 2016 is echoed by a traditional frustration with wealthy incomers, who have driven up house prices and turned properties into holiday homes.

Bailey Tomkinson, a 21-year-old singer-songwriter from St Ives, has written a song inspired by the G7 summit nearby. She says “Blood Red†captures her anger over the event. It is supposedly dedicated to sustainable development but the leaders are ferried around by plane and helicopter to a hotel where trees were removed to accommodate them all.

“It’s like Joni Mitchell — they paved paradise,†she said. “There are people coming who can change the world with a stroke of a pen, but what are they doing to help us? One mile from Carbis Bay, one-in-three children are born into poverty.â€

At the harbour in neighbouring St Ives, 70-year-old John Harry, who was born and raised in the town, gestures across the waterfront. “This place is full by 11am in the morning. St Ives doesn’t turn off any more. It’s like this 12 months of the year.â€

One of the local cafés is turning away visitors, informing them the next available lunch booking is July 28. Linda Taylor, Conservative leader of Cornwall council, says in some tourist hotspots “a mouse could not find a tiny bedâ€; she urged visitors to explore lesser known areas of the county.

Malcolm Bell, head of the Visit Cornwall tourist body, points out that his industry accounts for £2bn of turnover a year, 12 per cent of the county’s GDP and one-fifth of jobs. He says most local people see tourism as an economic necessity: “It’s like doctors saying the hospital would work a lot better if it wasn’t for all the patients.â€

Londoners are starting to make Cornwall their primary residence, working from home, maybe keeping a flat in the capital. Homes are being turned into Airbnb rentals. The county, which used to be seen as a traditional “bucket and spade†family destination, has moved upmarket.

Bell suggested the opening of the Tate’s outpost in St Ives in 1993 was a catalyst. David Cameron, the former prime minister, holidayed in Rock on the north coast — a village that in the summer drips with money and surf chic — and across the county hotels and holiday parks have been upgraded. “We’ve become a premium product,†Bell said.

Johnson is acutely aware that the G7 is not universally popular in Cornwall. Businesses have been forced to close, the Carbis Bay hotel is still a building site and Biden’s security team have left nothing to chance in terms of road closures.

But the UK prime minister has promised to invest in the county and to leave a summit legacy. Taylor said it was vital that this helps residents in places such as Pengegon, not just the places visited by the G7 leaders: “We have to make sure this legacy is spread across the whole of Cornwall.â€

[ad_2]

Source link