[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday to Thursday

Hello from Hong Kong, where quarantine restrictions have been eased for senior directors of big listed companies. But rather than flows of people, our main piece today is about flows of energy in an age of environmental transformation. Few would predict a future where the role of coal has not declined dramatically. But for now, the outlook is, to put it mildly, blurred.

We want to hear from you. Send any thoughts to trade.secrets@ft.com or email me at thomas.hale@ft.com

The link between trade and the price of coal

Tackling record commodity prices is on the minds of the Chinese Communist party’s top brass. And that raises questions over the production and trade of the country’s prime energy source: coal.

At a state meeting chaired by Chinese premier Li Keqiang last month, one line in particular will have jumped out to environmentally minded observers: the idea of tapping the country’s “rich coal resourcesâ€.

In September last year, China declared its commitment to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2060. But it still relies on coal for its electricity generation and, for now, it needs more of it.

“Almost all energy prices including coal, oil and gas have been rising rapidly in the past few months, prompting the Chinese government to prioritise energy security over decarbonisation concerns and reduction of fossil fuels like coal and gas,†said Cindy Liang, an analyst at S&P Global Platts, in late May.

Like many other commodities, prices for coal have recently soared. The wider raw material price rally has fuelled fears over inflation in China, with the same state council meeting emphasising the need to avoid them feeding through into consumer prices.

One of the main reasons why coal prices have shot up is a shortage in China, which is the world’s largest consumer of it. Analysts at Morgan Stanley point to a surge in power consumption, which in April rose 14 per cent year on year on the back of the country’s rapid recovery.Â

Coal production is up too, by 16 per cent in the first quarter compared with the same period last year, though mines were closed in early 2020 owing to the pandemic. But despite rising production, there are still pressures on supply to keep up with higher demand.

At the same time, domestic producers must comply with a tighter environmental backdrop, even if long-term targets are many decades away. Morgan Stanley notes that “domestic coal supply is under continued pressure from safety and environmental inspectionsâ€. Analysts at Argus, who anticipate higher coal consumption in the future, make a similar point.

“Market participants do not expect the government to allow significant production increases until after the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist party on 1 July,†they wrote last Friday. “In fact, strict environmental and safety curbs are likely to stay in place as longer-term rules, even after the celebration.†The state council meeting emphasised not only coal production, but also wind, solar, hydro and nuclear capacity.

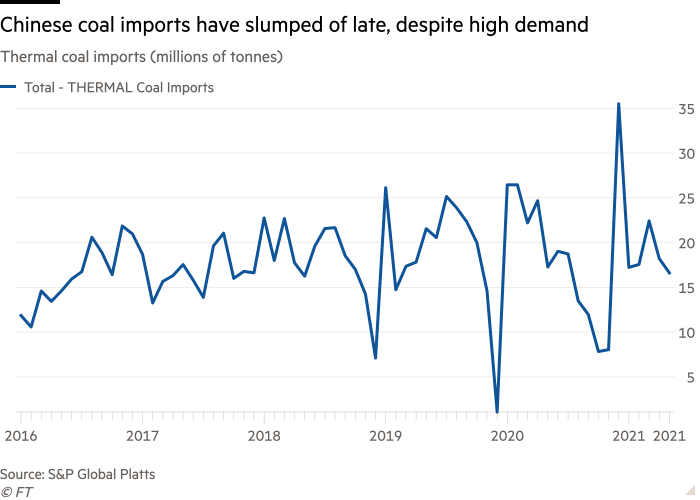

How does trade fit into this dynamic? Despite shortages, Chinese imports of thermal coal, which operate under a quota system and are only a fraction of total consumption, have plummeted by almost a quarter so far this year. That’s in part due to constraints on Australian coal amid worsening geopolitical relations between the two countries.

While prices are on the up the world over, foreign coal is far cheaper. In Australia, the active futures contract for thermal coal cut in Newcastle is $115.6 a tonne. In May, thermal coal futures on the Zhengzhou exchange surpassed the Rmb900 ($141) mark for the first time. As the chart below shows, this price discrepancy has gone on for years.

Against that backdrop, it might seem tempting for China to import more coal or at least avoid cutting imports further. The quota restricts imports to just 300m metric tonnes a year, compared with production of 3.81bn tonnes last year, according to S&P Global Platts. But another related dynamic is its push to reduce its reliance on other countries, which may explain the emphasis on its own resources.

Matthew Boyle, head of coal and Asia power at S&P Global Platts Analytics, expects coal production in China to peak in 2023. He says that China has continued to source coal from other countries, such as South Africa, but that the country is transitioning towards greater energy independence.

That ambition, which is also playing a role in gas, could point to a clearer trajectory for the trade of coal long before its consumption in China is significantly cut back. “As China moves towards self-sufficiency for its coal requirements,†he says, “its need for seaborne coal will become less.â€

Trade links

Tensions between Washington and Beijing rose another notch this morning, after the Biden administration said it was considering whether to launch a probe into imports of rare earth neodymium magnets from China. The probe would investigate whether tariffs could be introduced on security concerns. As those of you who read Ed White’s brief from Seoul last week will recall, China dominates the processing of minerals and rare earths vital for the production of goods such as mobile phones and electric vehicle batteries.

Relations between the EU and the UK over the Northern Ireland Protocol also look decidedly shaky, with Brussels now threatening to intensify action.

There are a couple of interesting reads on semiconductor chips. A big issue post-pandemic is going to be whether the automakers reduce reliance on just-in-time production, which left them with little to no chip inventory when the shortage hit. Bosch, Europe’s largest auto supplier, thinks the industry has to change tack and has warned carmakers must put “money on the table†and make a “rock solid†commitment to orders if they are to avoid a repeat of the events of the past year. There may be more trouble ahead for the likes of Europe’s automakers too, following an outbreak of Covid-19 in Taiwan, home to many of the chipmaking industry’s biggest participants. As Kathrin Hille writes, it is unlikely that this will affect the likes of larger manufacturers such as TSMC directly, but it may impact the smaller groups responsible for packaging their products. Nikkei also has an interesting take ($, requires subscription) on the vaccination crisis that has resulted from the latest surge in cases.

Industry groups from Japan and Finland, meanwhile, will conduct joint research and development of sixth-generation communications technology, looking to lead the creation of 6G standards in a field increasingly influenced by Chinese companies. (Nikkei, $)

Chad Bown of the Peterson Institute and Chris Rogers of S&P Global Market Intelligence have a new blog out, which posits that there was no US export ban on vaccines to India. However, they argue that the kerfuffle highlights exactly why a well-thought out global vaccine supply chain is so important. The post is summarised in a Twitter thread here too. Claire Jones

[ad_2]

Source link