More than 40 companies, ranging from the world’s largest management consultancies and pharmaceutical groups to a data company co-founded by a member of the Sackler family, have received years of detailed medical records from English hospitals, a Financial Times analysis has found.

There are at least 100 different NHS data sets that have been shared with companies, ranging from the broad Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database that lists every single patient who was admitted, their diagnosis, treatment and any outpatient appointments, to narrower sets of data on emergency care, mental health, mortality, cancer waiting times, sexual health and maternity services.

How the NHS uses and shares data has become a priority for the government, especially since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, with officials repeating the mantra that “data saves livesâ€.

Last month, the health department released a draft strategy promising to improve access to NHS patient data for researchers, so they can “provide innovative solutions†on everything from drug discovery to shielding programmes.

The NHS is also considering how to pool the medical records of 55m patients registered at local GP clinics into a single database that will also be shared with third parties.

But the FT’s analysis of the NHS Digital Data Release Register over the past five years, since it started publishing complete records, raises concerns over potential conflicts of interests and a lack of transparency about what happens to the data after it is shared.

Most of the third-party recipients of the data are public bodies, such as Transport for London, local councils and universities, which use it for planning and research purposes.

But sensitive patient data was also shared with 43 different commercial organisations including McKinsey & Company, KPMG, Novavax, AstraZeneca and marketing firm Experian. These accounted for 13 per cent of the total recipients of data.

Any organisation can apply for access to NHS patient data by following a stringent procedure to prove that it can keep it secure, and will use it solely for improving the health of English patients. The data is also pseudonymised, meaning that identifying information such as names and NHS numbers are removed.

Rory Collins, chief executive of UK Biobank, a genetic database of half a million UK patients and a professor of medicine and epidemiology at Oxford university, said that while records only stretch back five years, hospitalisation data had been available to third parties “for decades†and that “it is incredibly valuable for managing the health service and also for doing researchâ€.

But the FT found that insights from the data were often shared or sold on to other commercial entities and providers that use it to price products being sold back to the NHS, or conversely restrict the NHS’s access to analysis of its own data, creating conflicts of interest. Among the biggest criticisms focused on the opacity around the data’s fate after it leaves the NHS’s servers, and the lack of an auditing trail beyond the companies on the register.

“The idea of data going beyond the control of the NHS and not knowing where it ends up, concerns people,†said Natalie Banner, lead of Understanding Patient Data, a health data initiative by the Wellcome Trust. “Health data is particularly sensitive because it is a really precious relationship, collected in the context of your doctor; it makes it feel particularly distressing.â€

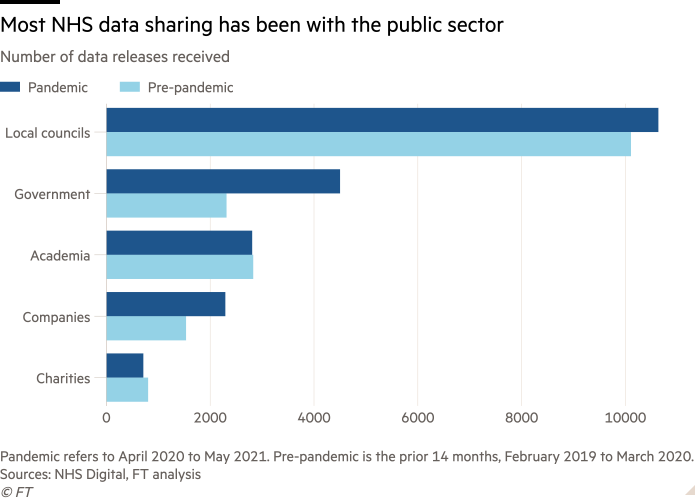

To examine which groups have benefited from the NHS’s vast patient data trove, the FT compared the recipients in the 14 months before the onset of the pandemic with the same period since.

IQVIA, a little-known US data company formerly known as IMS Health and co-founded by drug mogul Arthur Sackler, received the most data in the post-pandemic period.

IMS Health was well known for tracking the detailed prescribing habits of doctors in the US on behalf of drug companies, including Purdue Pharma, which was founded by the Sackler family and was responsible for the widespread distribution of OxyContin.

The specifics of what IQVIA provides its commercial clients are not clear from its NHS disclosures, but it says it has used this data for at least 28 projects in 2020 alone, to provide analysis to pharmaceutical and medical companies and to the NHS’s various bodies.

IQVIA also purchases medicines supply data from NHS hospital pharmacy systems, then sells an aggregated data set on to drug companies.

But in an example of the power asymmetry between private sector companies and the NHS, the health service’s own access to IQVIA’s data set is restricted according to research in the British Medical Journal by the doctor and academic Ben Goldacre. In certain cases, the NHS cannot even release data to UK regulatory bodies without prior permission from IQVIA.

“This hospital medicines supply data already exists. It is provided by NHS hospitals to the drug industry for marketing purposes,†Goldacre wrote. “But the restrictive terms of the [agreement] mean that we are unable to use it for open audit to improve quality, reduce avoidable expense, and make prescribing safer in hospitals.â€

Since the pandemic began, the NHS has accelerated its data sharing, with the number of corporate recipients rising to 29 between April 2020 and May 2021, from 21 in the same number of months before the pandemic.

These numbers do not include companies, such as the data analytics group Palantir, that were given access to health data under emergency measures last year for pandemic-related work.

Health data has provided the NHS with critical insights under extreme pressure, for instance identifying dexamethasone as an emergency treatment for Covid-19, a breakthrough that has to date saved 22,000 lives in the UK and another 1m worldwide.

“The [coronavirus] vaccine rollout could not have been delivered without effective use of data,†said Simon Bolton, chief executive of NHS Digital. He added that the data could only be accessed by organisations using it for healthcare planning and research purposes, and that this would be overseen by the NHS.

Critics argue that patients are often unaware of the NHS’s data-sharing practices, and even if they withhold consent it can be difficult to prevent their data from being disseminated externally.

While the NHS provides a “national data opt-out†option for patients, it still shared full, pseudonymised data sets with external organisations in 84 per cent of instances when opt-outs had been exercised.

“The fact it is being used at 10-20 per cent effectiveness is horrendous. Patients must have confidence that if they have expressed opt-out that will be respected,†said Phil Booth, head of the medical privacy campaign group MedConfidential.

The NHS said it had primarily ignored opt-outs in cases when patients are not identifiable because names and NHS numbers had been removed from individual records that were shared. Researchers have questioned how effective this type of “pseudonymisation†is in genuinely protecting privacy.

Campaigners also worry that while the NHS stipulates in its contracts with third parties that it will track where the data ends up, this is impossible in practice.

“There is no end-to-end audit or transparency on all of the users of the data. There are black holes here. We need to see comprehensively all the flows of data,†said Booth.

For instance, British medical data company Compufile Systems states that its data analytics services are offered to at least seven “medical device, medical supply and life science companiesâ€. It is unclear if the NHS receives any proceeds from its valuable data sets being used to develop commercial products.

The company said there was “mutual benefit†to both parties because “the pharmaceutical company builds reputation and strengthens relationships with their customer [the NHS]â€. It did not respond to request for comment.

In another case, a company called La-ser Europe, owned by US drug development firm Certara, used hospital data last year to study a specific subpopulation of haematological cancer patients. The study was funded by global biotech firm Amgen, which manufactures therapies for these cancers.

While the company claims that the data will not be used “primarily†for marketing purposes, it acknowledges that Amgen could use the NHS data to price its products, and to lobby for recommendations from NICE, the independent agency that approves NHS funding for new treatments.

“What are the financial relationships here? Some drugs are very expensive and a pharmaceutical company may be trying to get its drug approved by NICE,†said Booth. “The best way to do that is to prove there is demand for it. If this particular type of cancer is underserved, you can use that to lobby NICE to get your drug and then make some money. That is a possible interpretation.â€

Wellcome Trust’s Banner suggested that NHS Digital could provide a health data “billâ€, similar to a council tax bill that shows what your contribution has been spent on.

To this end, health economists have been trying to establish how to value health data, and therefore protect the NHS from being exploited by the private sector. Some have suggested that a fair return for the NHS would be if any financial proceeds from its health data are ringfenced for public health and social care.

Annemarie Naylor, who until recently was the director of policy and strategy at Future Care Capital, a health policy charity, said: “We all want innovation in treatments and more preventative health service that is cost effective, but we want to be assured no one is benefiting disproportionately and giving away our data, rather than [it] being deployed strategically by the government.â€

The UK campaign group MedConfidential pointed us to the NHS Digital Data Release Registers, which were used to conduct this FT analysis.