As tensions between Beijing and the outside world ratchet ever higher, multinational companies that have invested huge sums over the last two decades in what they believed was the market of the future, face a crucial choice: Do they begin to draw down their investments and limit their exposure to China in anticipation of a worsening of relations? Or do they stay the course, hoping relations stabilize? In a candid interview with Newsweek, the CEO of a major Japanese multinational, Takeshi Niinami of Suntory, the beer and spirits maker, acknowledged the increasing risks of doing business of China—going so far as to use the word “confiscation” to describe the worst-case scenario of what could happen to a company’s assets on the mainland.

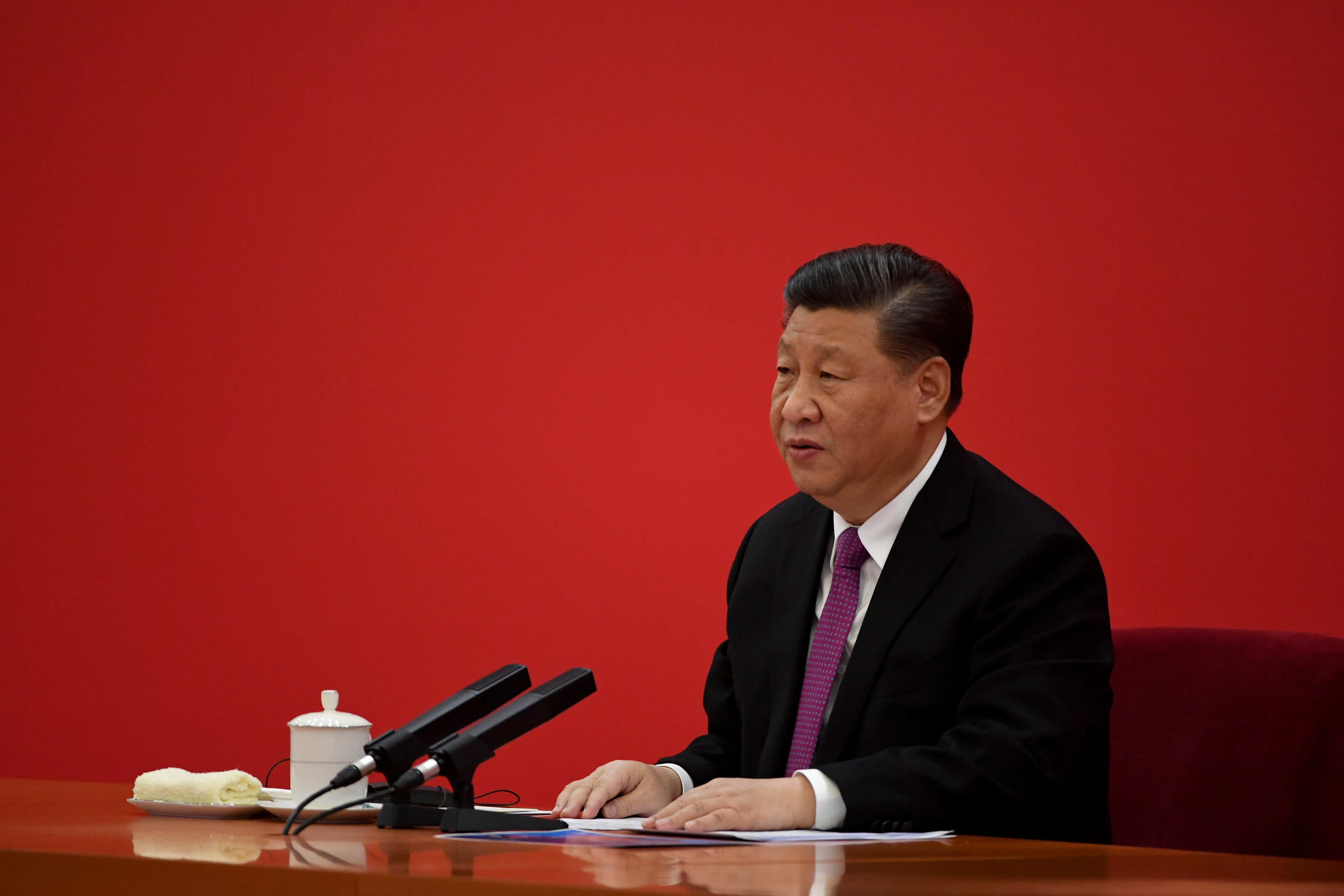

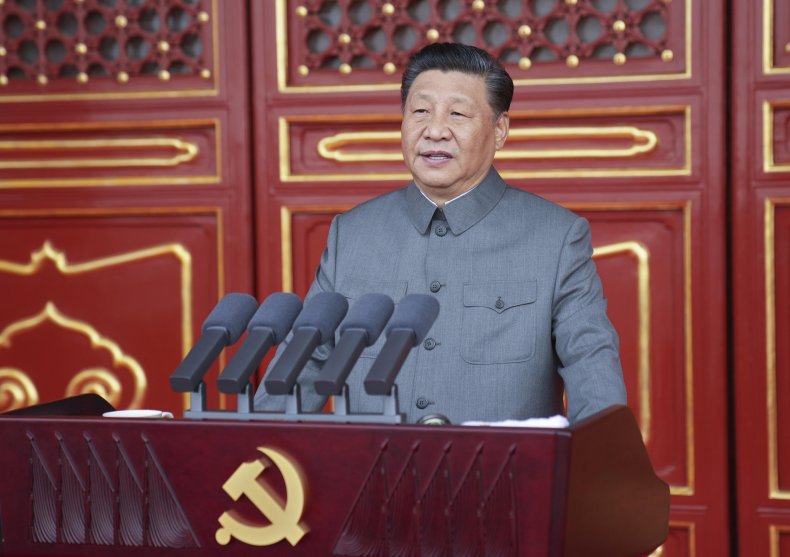

In this photo provided by China’s Xinhua News Agency, Chinese President and party leader Xi Jinping delivers a speech at a ceremony marking the centenary of the ruling Communist Party in Beijing, China, Thursday, July 1, 2021. China’s Communist Party is marking the 100th anniversary of its founding with speeches and grand displays intended to showcase economic progress and social stability to justify its iron grip on political power that it shows no intention of relaxing. Li Xueren/Xinhua via AP

“We have to decide whether to expand production facilities or not in China,” Niinami says. “Should we invest more in China knowing that the possibility of confiscation [exists]? Do we take the risk, or not? To what extent? If it’s 10 billon [yen, i.e., $91 million], maybe not. Five billion? Probably. So we have to judge to what extent we can tolerate confiscation. That’s risk analysis. And I believe we have to decide sooner or later.”

Every CEO doing global business makes such calculations, but China’s size and rapid growth means those conversations usually stay behind the boardroom door. Niinami acknowledged it frankly because he and his China team at Suntory are comfortable with their own conclusion: “We definitely have to be there,” he says flatly.

That’s a conclusion Japanese multinationals have been making for decades. China is Japan’s biggest trading partner, and the countries are deeply intertwined economically. In 2020, a year in which China supplanted the United States as the largest overall recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI), Japanese investment in China was $11.3 billion. Overall it has invested $141.6 billion there—nearly $20 billion more than the U.S. has.

Suntory’s conclusion is driven in part by the familiar reasons driving decision-making for any company producing products for the China market: “We have to produce products suited for Chinese consumers,” Niinami says, and to do so requires “more time and resources.”

Setting up a business-to-consumer digital platform—”B to C”—is critical for Suntory, the CEO says, and that means working with Chinese companies like Alibaba and Tencent, companies that have troves of real-time consumer data. He does so knowing full well that “the data is always monitored by the government of Beijing.”

Japan’s government and its companies, like their counterparts in the U.S., have become much more wary about investing state-of-the-art technology in critical sectors such as artificial intelligence, telecommunications and computers—all areas with national defense components. A consumer products company like Suntory can feel comfortable investing in China, “but not technology [companies],” Niinami acknowledges.

Ironically, one of the reasons a consumer products company like Suntory needs to be in China is technology. Specifically, China’s advances in artificial intelligence. “Staying in China means a lot, because they have the state-of-the-art AI technology. It’s really advanced in the consumer space. So we definitely have to be there,” he says. ”I would take that risk.”