[ad_1]

European countries are preparing to scale back their unprecedented support measures for workers affected by the coronavirus pandemic, but millions of people still rely on the furlough schemes, fuelling economists’ calls for greater urgency in helping them find work in other industries.

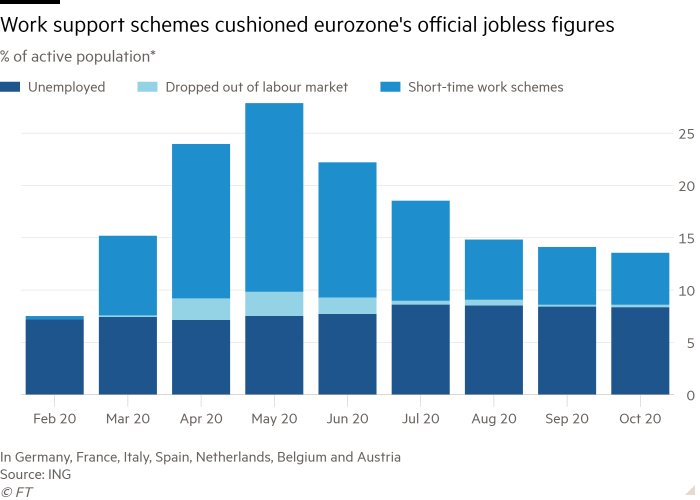

More than 6m jobs across leading eurozone economies were still being supported by the main government furlough, or short-time work, schemes at the end of 2020, according to an FT analysis of national statistics.

This is down from more than 23m in April, at the height of the pandemic’s first phase. But the number being furloughed has risen again in recent months as restrictions tightened in response to a virus resurgence. The figures do not include many self-employed, temporary and casual workers who are covered by different schemes in some countries.Â

In Germany, the number of short-time workers rose by almost 20 per cent month on month in January to 2.6m — 7.8 per cent of all employees, according to the Munich-based Ifo Institute. The number of people on France’s activité partielle rose by 1.3m during its November lockdown, though it dropped again in December.

The short-time work scheme “has saved many jobs in our industryâ€, said Stefan Wolf, head of the German metal and electrical industry employers’ association. Just over four in 10 of its members were still using it at the end of January, he said, including ElringKlinger, the business he runs that makes gaskets and plastic panels for cars.

But despite continued dependence on these schemes, they are due to be scaled back in the coming months.

From March, workers on France’s furlough scheme will receive a smaller proportion of their total salary and more of it will have to be paid by their employers. In Spain, furlough has been recently extended to May but business exemptions from social security payments will be limited to hard-hit sectors.

Italy’s scheme is also due to expire in the spring, and its ban on dismissal for economic reasons is set to come to an end in March.

Some scaling back is necessary to encourage people to move on from jobs that have become economically unviable, economists argue.

Andrea Garnero, labour market economist at the OECD, said it was “essential to promote the mobility of workers from subsidised to unsubsidised jobsâ€, adding that the focus of furlough schemes “should be on jobs that are likely to return to being viableâ€.

Options for further restrictions include shifting more of the cost of furlough on to companies. Eligibility criteria, generosity and duration of benefits could also be limited to avoid schemes that simply delay rather than avert unemployment.

“Firms in sectors not subject to mandatory restrictions could be asked to bear part of the costs of short-time work schemes, or limits to the maximum duration of job retention schemes could be introduced,†said Garnero.

Jessica Hinds, economist at Capital Economics, said the schemes’ “eligibility for support or the amount on offer may also be restricted, perhaps based on lost turnoverâ€.

But economists and policymakers are becoming concerned about the consequences if schemes are scaled back, fearing a sharp rise in unemployment if they are wound down before the pandemic is over.

Bert Colijn, economist at ING, warned that “at some point, more businesses will start to restructure and delayed unemployment could still be the result of the eventual end of the schemesâ€.

Earlier this month Christine Lagarde, European Central Bank president, urged countries to “beware of the cliff-edge†in public spending and “continue to shelter employees . . . throughout 2021, as hopefully we see the result of vaccinations and gradually removed lockdown measuresâ€.

Some governments are already trying to encourage workers to retrain. In the Netherlands, employers applying for job retention support have to declare that they actively encourage training. In France, the job retention scheme benefit increases from 84 per cent of the workers’ net pay to 100 per cent when they take up training. In Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, governments have provided fully funded training courses and allocated funds for businesses to provide training or hire trainees.

There are also indications that the use of furlough schemes is becoming more concentrated in the worst-hit industries.

In January, 56 per cent of the German workforce in hotels and restaurants was on short-time work, the largest proportion of any sector, according to Ifo. In contrast, fewer than 9 per cent of manufacturing workers were in such schemes, down from 30 per cent in May.

Ingrid Hartges, general manager of Dehoga, the German hotel and restaurant association, said that even with furlough, “it is becoming increasingly difficult for companies to keep their employeesâ€. The number of workers employed by German hotels and restaurants fell 9 per cent year on year to just under 1m in November — suggesting they are finding opportunities in other industries.

Katharina Utermoehl, economist at Allianz, said that although furlough schemes were “single-handedly responsible for creating a labour market miracle in Europeâ€, they were “no panaceaâ€.

“The longer the crisis lasts, the greater the need to complement job retention schemes with active labour market policies, to put greater emphasis on creating the jobs of the future rather than saving today’s jobs,†she said.

[ad_2]

Source link