[ad_1]

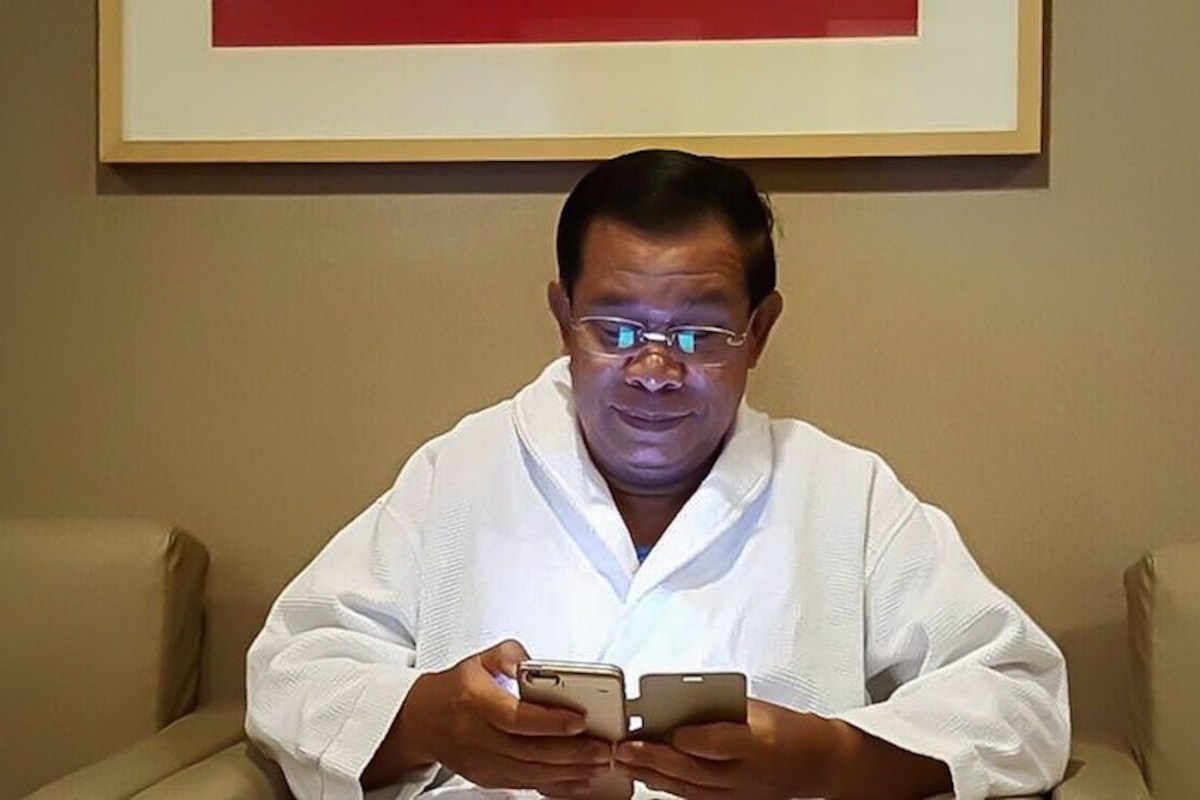

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen signed a sub-decree on February 17 to create the country’s long-planned National Internet Gateway (NIG), a new Chinese-style firewall that critics fear will give authorities even more draconian powers to shut down online free-speech.Â

According to a draft of the sub-decree leaked last year to the media, authorities want to create a gateway in order to boost “national revenue collectionâ€, “protect national security†and assure “social order,†all ill-defined terms that are currently used in other legislation to imprison government critics.

Article 6 of the leaked copy stated that the NIG operator would work with the government “to take actions in blocking and disconnecting all network connections that affect safety, national revenue, social order, dignity, culture, traditions and customs.â€

Under the scheme, all internet traffic, including from overseas, will be routed through a single portal managed by a government-appointed regulator. Internet service providers (ISPs) who historically have been left to manage Internet traffic flows will have 12 months to re-route their networks through the single gateway.

The NIG operator will also be required to store all Internet traffic metadata for 12 months, which can be assessed by the authorities. Government spokesman Phay Siphan denied in an AFP wire report that the NIG system is intended to crack down on free speech, although he added that the authorities “will destroy those [internet] users who want to create rebellion.â€

Cambodia already has several regulations to strictly control online content. The 2015 telecommunications law allows authorities significant powers to request user traffic data from ISPs.

The country’s criminal codes as well as “fake news†legislation has been used frequently to imprison activists or ordinary users who are critical of the country’s authoritarian government.Â

The number of Internet users arrested or imprisoned for writing politically-sensitive posts on social media has risen in recent years while the long-ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has attempted to monopolize political narratives through its own social network accounts.

However, up until now, the Cambodian government could only be reactive to online dissent by censoring content or arresting Internet users after messages were posted online.Â

While attempts were made in the past to block politically-sensitive websites, such as the Khmer-language versions of international newspapers, these restrictions were easily bypassed through VPNs and not applied equally across ISPs. Â

However, concentrating all Internet traffic through one gateway will allow authorities to better curtail online free-speech before content is posted, therefore adopting a China-like system of preventative censorship. Â

It will now also be much easier for authorities to order far-reaching Internet blackouts and possibly ban access to social networks for a limited time period.Â

Because the NIG operator will be required to keep traffic data on each user, it is believed that this will cause even more self-censorship as well as force Internet users to second-guess whether they will face future punishment for clicking onto a certain website. Â

According to the leaked text, the operator will be required “to take actions to block and disconnect all network connections that affect safety, national revenue, social order, dignity, culture, traditions and customs.â€

Comparisons have already been made to China’s so-called “Great Firewall†but Cambodia’s latest move will be much weaker.Â

An essential element of Beijing’s vast online surveillance state is the absence of foreign-owned social networks like Facebook, which is banned in China but is king of social media in Cambodia.

Instead, the most popular social networks in China are domestically-owned, like Weibo and WeChat, whose owners are far more willing to censor on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party.

Cambodia is highly unlikely to either force most of its citizens off US-based Facebook nor create a domestically-owned rival platform.Â

As a result, Cambodian authorities are likely to try to mesh Chinese-style surveillance with the more subtle example of neighboring Vietnam, where its ruling Communist Party has forced the likes of Facebook and Google to censor internet users on its behalf.Â

This was achieved by the controversial Cybersecurity Law that came into effect in January 2019 and which forced overseas tech firms like Facebook to set up local offices and store their data in Vietnam.Â

It is believed that by rerouting all overseas Internet tariff through a single gateway, Cambodian authorities will gain more leverage over foreign-based social networks like Facebook, including the threat to shut off its traffic and vital advertising revenue.Â

Similar threats by Vietnamese authorities to cut off advertising on Facebook, its main source of revenue, is thought to be the main reason why the Silicon Valley-based social network has increased its censorship of politically-sensitive comments on Vietnam in recent years.Â

At the same time, the Cambodian government is also writing up a draft cybercrime law, which went through its third phase in mid-2020. It is expected to be finalized by the end of 2021. Â

With a population of over 16 million, Cambodia reportedly has 14.8 million mobile internet subscribers and roughly 10.9 million Facebook users.Â

There are also concerns over who will be the NIG operator, as the government will appoint either a privately-owned or state-owned firm to manage the single gateway and work alongside the Telecom Ministry.Â

Questions have already been raised as to whether there is a Cambodian firm with the skills and experience to handle the high-tech task. If not, it is possible that a foreign firm, possibly Chinese, could win the contract to become the NIG operator.

Given Cambodia’s shoddy standards on corruption – it was last month ranked 160th out of 180 countries and the worst in Southeast Asia in Transparency International’s latest Corruption Perceptions Index – there is little optimism of an independent and transparent tender process to decide which firm is appointed the NIG operator. Neither are the terms of this deal likely to be made open to the public.Â

Some businesses aren’t happy with the development. A similar proposal was made by Thailand’s military junta not long after its 2014 coup, but the measure was dropped in 2015 following opposition from the business community, which argued that a single gateway would inevitably raise costs for the private-sector.

Similar complaints were made by Cambodia’s business community last year when the text of the sub-decree was leaked, although this clearly has not been heeded by Phnom Penh.Â

On the one hand, proponents of the NIG scheme assert that it will provide authorities with better means to collect taxes from tech firms, crack down on cyber-security threats and regulate what has typically been a very decentralized market for years. Â

On the other hand, industry groups argue that having a single gateway will reduce connection speeds and increase the risks of nationwide Internet blackouts if technical problems arise, which will significantly affect the operations and profits of businesses reliant on the Internet.Â

The Asia Internet Coalition, a lobbying group composed of the world’s largest tech firms, including Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Twitter, wrote to Hun Sen in December appealing for him to not support the NIG scheme.Â

“Having a single national internet gateway creates concerns in terms of failure, as there is no alternative to the country’s connection to the global internet,†it stated in an open letter.Â

It added that the NIG system “will not achieve the stated objective of enhancing the effectiveness of Cambodia’s internet connectivity. What it does is grant the government extraordinary powers to arbitrarily block online content or network connections.â€

Indeed, the timing is suspect. The single gateway is expected to be launched next year, when Cambodia’s political crisis could reach a new peak.

The ruling party forcibly dissolved its only viable opponent, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), in 2017 on the flimsy allegation of plotting a US-backed coup. This allowed the ruling CPP, which has been in power since 1979, to create a de-facto one-party state at the 2018 general election.

But its legitimacy could be tested at local elections in mid-2022 and a general election the following year, especially if the now-exiled leaders of the banned CNRP are able to return to the country. So far, Hun Sen’s regime has stymied several of their attempts to do so. And any news on the CNRP’s calls and activities could soon be stifled by the NIG.

[ad_2]

Source link