[ad_1]

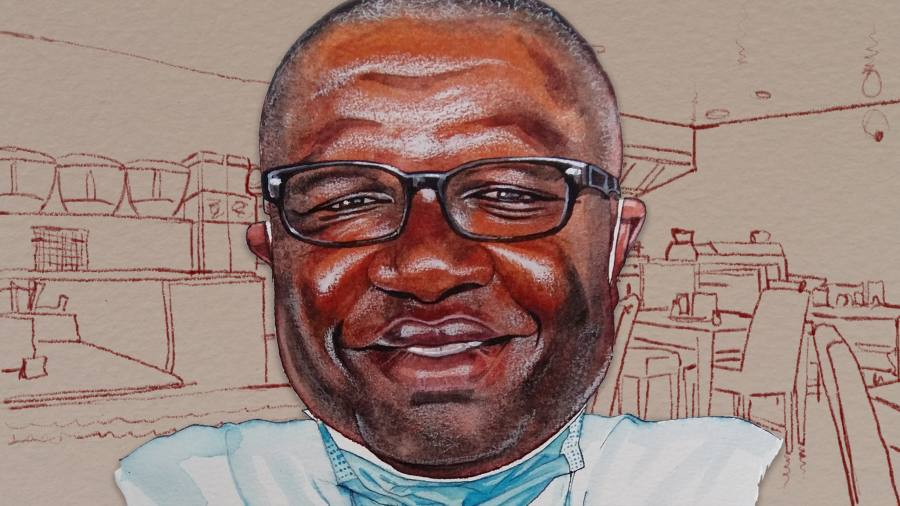

I arrive at the dusty campus of Redeemer’s University in rural Osun state to meet Christian Happi, after a five-hour drive up through hardscrabble south-western Nigeria from Lagos. Behind the one-storey building that is currently home to the African Center of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases are plywood crates which once housed components for million-dollar Illumina gene sequencers.

It was here that Happi sequenced the first coronavirus samples in sub-Saharan Africa, within days of its being diagnosed in Nigeria, and recently identified the South African variant’s first appearance in Africa’s most populous country. And this was merely the latest vital intervention against deadly disease by one of Africa’s leading scientists. He helped to sequence the Ebola genome in 2014 and was a key figure in Nigeria’s successful quashing of an outbreak. His research has also greatly expanded our knowledge of Lassa fever, another haemorrhagic disease that kills thousands every year.

Now the 52-year-old Cameroonian is building one of the most advanced laboratories in Africa, in the hopes of bringing greater scientific autonomy to a continent too long relegated to being the subject of research — rather than its author.

“What I like about it is that it is something marvellous in the middle of nowhere,†he says. “I want people that are focused. If you go to that place, and you are not someone who is focused, you can’t stay there . . . It’s only when we all have purpose that we can actually change the narrative.â€

Before we head off for lunch he takes me down the road on a tour of what will be the permanent home of the ACEGID, rising from the scrubland at this private university founded by one of Nigeria’s biggest megachurches.

The $4m modern earth-and-stone building, with its level-three biosafety lab, is backed by the World Bank, the US defence department, the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and others, whose $20m funding includes grants for research. Happi has also secured $100m over five years from “some of the biggest names in Silicon Valleyâ€. His mission is striking: to build a pandemic early detection system.

Sentinel, as he calls the system, has already proved successful in detecting outbreaks of Lassa fever and yellow fever. He wants to be able to go a step further and deploy rapid diagnostic tests that would identify pathogens using Crispr gene-editing technology and automatically send results to the health authorities. Sub-Saharan Africa is where 70 per cent of pathogens with pandemic potential emerge.

“I’m a pathogen hunter . . . but we’ve been playing defence. And for me, with the knowledge, the skills, the technologies available, we can now play offence,†he says. “We need to be more proactive, we need to be ahead of the curve.â€

After a quick tour we are off to Ibadan, where Happi lives with his wife and three children, about two hours back towards Lagos. We wind our way through the heart of Yorubaland, past women in faded wax print dresses hawking roasted cane rat — a bushmeat delicacy splayed out, grinning and spatchcocked, on wooden sticks.

It is past 3pm by the time we pull in to Wimpy, the sort of Lebanese restaurant common across west Africa, with an extensive spiral-bound multi-cuisine menu — burgers, pizza, shawarma, Chinese — and sit at a grey plastic table on the covered concrete patio. We are the only customers. Ibadan’s knotty traffic roars behind us.Â

When we meet in late January the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic is surging across Africa. It is far worse than the first, when Nigeria recorded just 100 or 200 confirmed cases a day for a population of 200m. (In the weeks after our meeting, the rate of infection has slowed again.)

Since the virus first arrived in Nigeria in March, when Happi confirmed the first case and then sequenced the virus’s genome within 72 hours, he has been wary of making bold pronouncements. I ask him why the pandemic has been so soft in Africa. He ticks off the usual answers: the median age of sub-Saharan Africa is only 18 compared to over 40 in Europe; many Africans live and work outside, providing some natural social distancing and ventilation.

African DNA is the world’s most diverse, because 99 per cent of our evolutionary history occurred on the continent. We can’t yet rule out that those diverse genomes — buffeted for millennia by environmental pressures, including disease burdens far beyond what other peoples experienced — does not offer “some level of innate natural immunityâ€, he says. He also notes that African countries locked down far earlier compared to the west, often with just a few confirmed cases.

“But . . . the west tends not to give credit to Africa where it deserves. We need to be truthful — Africa has more experience when it comes to handling epidemics or pandemics,†he says. “It’s not always a matter of resources or money — it’s experience, and we can’t deny that to Africa.â€

The waiter seems to be maintaining his social distance, so we keep chatting. I ask when Happi thinks we might finally see vaccines rolled out in Africa. He looks at me over his glasses, and laughs sharply.

“Earliest — earliest! Middle of the year. Earliest! That is after the US has finished its own vaccination program. After Europe is all covered. Then they will now look and say, oh you guys don’t have vaccines? OK, here you go.â€

Happi was born in neighbouring Cameroon, the middle of seven children in Sangmélima, in the heart of the great equatorial forest that covers Africa’s middle. It is malaria country, and he was often sick. One day, when he was seven or eight, his mother was carrying him home from the hospital.Â

“I was on her back and she stopped to rest and I asked her: ‘Why am I always sick?’†he says. “She said she didn’t know, and I told her that when I’m older and if this disease is still around, I’m going to find a cure for it.â€

He earned a scholarship to the only university in Cameroon. He chose biochemistry, inspired by an article he’d read about James Watson and Francis Crick and their discovery of the structure of DNA in a magazine at his primary school library.Â

“The power behind biochemistry, being able to discover the structure of DNA, knowing that DNA was, you know, the fundamental unit of life!†Happi says. “I could have a kind of, you know, superpower, and then I could find a cure for malaria . . . for my people.â€

For his master’s, he moved to the University of Ibadan to research the human response to malaria vaccines and drugs. He wanted to examine the resistance of some malaria strains to chloroquine, which had long been an effective treatment. “I started thinking about how I could reverse that mechanism of chloroquine failing,†he says. “But in order to do that, you first of all have to understand the genetic make-up of malaria.â€

It was 1995, and full mapping of the human genome was still eight years off, but great strides were being made in how we understand disease. A chance meeting with immunologist Dyann Wirth, one of the world’s foremost experts on malaria, earned him an invitation to Harvard to present his idea. He spent the next 12 years working there on malaria research. It was a stark change from how he had worked in Nigeria, where, as with nearly every African scientist then — and many now — his scientific research was purely conceptual.

“There was no equipment to do anything — it was all theoretical, always,†Happi says. “At Harvard I have access to all the equipment, I have access to all the resources. And then I can start exploring, using genetic engineering and biotechnology to explore . . . but I still had a leg here in Africa, because I wanted to be present here all the time.â€

At this point, 50 minutes into our conversation, our waiter appears. Happi orders a Chapman, a sweet Nigerian non-alcoholic fruit cocktail popular across west Africa. I ask for a Star, the classic Nigerian lager, which isn’t on the menu but which the waiter says he’ll send someone to buy. He asks if it’s OK if he comes back with a Gulder, another local lager. In the heart of the bone-dry Harmattan, I tell him anything cold will do.Â

In 2014, Happi was at home in Ibadan, where he had relocated in 2011 with $1.25m in US National Institutes of Health funding to build a genomics programme at Redeemer’s, when he got the call that the first suspected Ebola patient had landed in Lagos. The disease had ravaged Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, smaller countries where it would eventually kill more than 11,000 people. Everyone feared that once it hit Lagos — that crowded, chaotic megalopolis — it would explode across the country.Â

“This was the moment that now we need to act to save our people. I told my kids, listen, I have to go deal with a very dangerous pathogen. I told my wife, if I die, don’t cry — know that I’m dying a good death because I’m doing it for my people.†Happi drove to Lagos, where he worked with the team there to test the patient and, in the months that followed, with authorities to contain the epidemic. It was a rousing success: just 19 people in Nigeria were diagnosed with the disease.Â

“I had to improvise a lot,†he says. Ebola was supposed to be handled in a category-four biosafety facility — the most secure and high-tech — but he had to do his work in a level-two room because that was all he had. “Suicidal!†he laughs.

Africa’s history with the west is littered with examples of plunder masquerading as benevolence, and science is no exception. Doctors and researchers who came to help during Ebola flew out with more than 269,000 blood samples from patients in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. That has meant researchers in those countries cannot access samples that in many cases they had collected.

“All those superpowers, all those parachute researchers . . . they pretended as if they want to help, but the real agenda was to control samples, so they can do all kinds of research on them.â€

Our drinks arrive. We both decide to order the shish taouk, which comes with fries. It will be another 45 minutes before it arrives. We keep Covid-safe by skipping the bread on the table.

Happi continues, explaining his fierce opposition to drop-in science. “They come into your setting, they don’t understand how your health system is structured, they will be directing you how to do things . . . in a country they don’t understand!†Happi says. “What prevents [them] from coming and training Africans to do it themselves?â€

Happi called the health minister when he made the Ebola diagnosis. “When the Germans and the WHO and the Americans came to him and said, ‘we need to validate it to confirm the diagnosis’, he told them to go to blazes!†he says.

“We changed the whole narrative — what people thought was impossible, we showed them it was possible. What people thought they would come and help us to do, we did ourselves — and that to me was just amazing.â€

He was part of a team that sequenced the Ebola genome. “We made the data openly accessible and available . . . Those that want to do vaccines, use it; those that want to do therapeutics, use it; those that want to do diagnostic, use it . . . And within four months, we developed a rapid diagnostic test, where turnround time of diagnosis went from five or six hours to 10 minutes.â€

Wimpy Ibadan

Onireke Road, Ibadan, Nigeria

Shish taouk x 2 9,200 naira

Chapman 700 naira

Small bottle of water 200 naira

Star lager 500 naira

Tip 2,000 naira

Total 12,600 naira ($33)

Our food finally arrives. My Star is long gone. The chicken is tender and flavourful, and covered by a thin pita. The fries are of frozen vintage. I’m not complaining — this is a very solid entry of a dish I eat often.Â

We’re both adding generous portions of red chilli paste to our chicken. “You can’t live here without eating chilli,†Happi says. I mention a spaghetti bolognese I ordered in Lagos soon after I moved that had me sweating like a Carolina Reaper. “Because in Nigeria, if someone gives you tomato stew, it’s 90 per cent pepper,†he laughs.

Happi always mentions “my peopleâ€, “the African peopleâ€, and “Africaâ€, rather than Cameroon, where he’s from. I ask whether he wishes he could have started this centre in his home country.

“I’m more pan-African,†he says. “I made a conscious decision to come here, because I knew that if I impact Nigeria, I will impact Africa more.â€

He left Harvard to, as he says repeatedly, “change the narrativeâ€.

“Any time I looked at Africa, it’s all these negative stories,†Happi says. “I felt like I’m here [at Harvard] sharing this knowledge, giving what I have, yet my people are still looked on as if they are not human beings.â€Â

Over the past year, African governments have struggled to acquire nearly everything related to the pandemic — from masks to PPE to medical oxygen to ventilators and now vaccines. I wonder what it tells Happi.

“It tells me that Africa has to do better in investing in recent developments in the field of infectious disease,†he says. “And I hope that Africa has learnt that if you had invested in vaccine development and developed one or two vaccines, then we would be at the table. But we refuse to prioritise our investment . . . And it’s not because there are no resources on the continent — there are. But they are just not priorities.â€

Might Covid change that? “It should change because the economic losses due to Covid are amazing. A lot of African governments are broke,†he says. “If the leaders were people that were a bit more educated, more enlightened, they will [understand this]. But unfortunately, I doubt it.â€

Happi believes that we will be able to spot the next pandemic before it overwhelms us, in part because the global community realises that investing a few billion dollars now beats losing trillions later. Africa, he says, needs to be at the centre of that conversation.

“Look at how this started in Wuhan and in little or no time we were all into it. So would it make sense to invest and make sure you’re combing the world to make sure you’re going to prevent this kind of thing from happening? The answer is Yes,†he says. “If a disease emerges from anywhere within Africa, it takes 36 hours to find itself in New York. It might take another 24 hours to Tokyo . . . and then trouble starts.â€

Neil Munshi is the FT’s West Africa bureau chief

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen

[ad_2]

Source link