[ad_1]

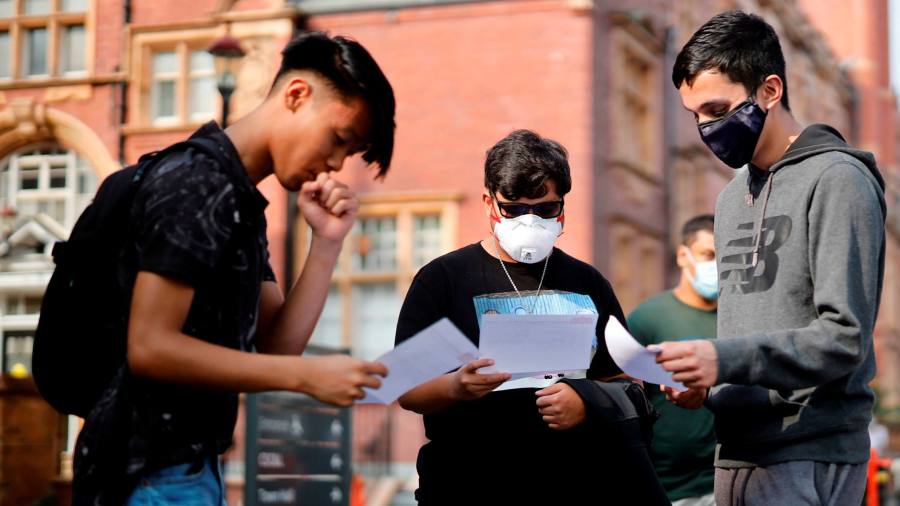

UK universities are bracing for another year of Covid-related disruption as experts warned that inflated grades caused by a second summer of cancelled public exams would leave many admissions departments highly stretched.

A government decision to allow A-level grades to be awarded solely by teacher-assessment is expected to cause 10 to 15 per cent grade inflation for a second year running, according to two people familiar with Department for Education projections.

Allowing more 18-year-olds to receive top grades than in the pre-Covid era would put pressure on leading universities, particularly for laboratory-based courses with limited capacity, such as medicine and engineering, senior industry figures warned.

Universities at the lower end of the academic spectrum will conversely need to find capacity to help students who would not otherwise have achieved high enough grades to get to university cope with degree-level learning.

Announcing the policy formally in the House of Commons on Thursday, education secretary Gavin Williamson said the exam grading process would be “fair to every studentâ€, adding: “It is vital they have confidence that they will get a grade that is a true and just reflection of their work.â€

Williamson also stressed that grading would not involve algorithms following last summer’s results fiasco which saw the government face a furious backlash from schools and parents after it used technology to moderate A-level results that discriminated against the less well-off.

Robert Halfon, chair of the Commons education select committee, warned against “a wild west of gradingâ€, but conceded that the decision to allow teachers to assess grades was “the least worst optionâ€.

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor of the University of Sunderland, said that while the effects of the government’s announcement would be felt most severely in selective subjects, many institutions would feel the squeeze at both the top and bottom ends.

“At Sunderland, we are likely to be managing both kinds of issues, given that we have a medical school but we are also used to taking students who do not necessarily hold traditional qualifications, or enter with lower grades,†he said.

However, despite the additional pressures, the Russell Group of 24 leading research universities, which includes Oxford and Cambridge, said it was making contingencies to increase its intake if necessary, as it did last year when numbers increased by 15 per cent.

Tim Bradshaw, the group’s chief executive, said the universities would be as “flexible as possible†on admissions, but urged the government to consider increased financial support to help institutions to maintain per-capita funding for medicine and laboratory-based subjects.

“It will be important to ensure that the per student funding provided by the government for higher-cost subjects is not further diluted by any increase in student numbers caused by grade inflation,†he added.

Greg Walker, chief executive of Million Plus, which represents post-1992 universities — a group of former vocational institutions or polytechnics — also said that colleges could cope with expanded admissions, but only in the short term.

“It will be a challenge as the years go by. This kind of instability is not sustainable for more than a couple of years,†he added.

Universities UK, the sector’s lobby group, said that institutions would work to accommodate students, even if that meant deferring courses or offering alternatives if a course was full. “Universities will help students find suitable, alternative study choices,†the group said.

Still, experts warned that grade inflation — and the fact that results will remain uncertain right up until early August — would inevitably create pressure.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, a think-tank, said that while in the short term parts of the university sector might welcome extra students in order to compensate for frozen tuition fees and a drop in lucrative international student admissions because of Covid-19, it would create difficulties in the longer term.

“This will cause headaches down the road. We have a very hierarchical and selective university system, and the less meaning that grades have, the harder it is for universities to do their job — it is very difficult to unfreeze grade inflation once it has begun.â€

[ad_2]