[ad_1]

Who subsidises whom?

At Budget time, Conservative chancellors normally have to tick only a few boxes to keep their MPs and voters happy. Alongside reasonably careful stewardship of the nation’s finances, they have to keep fuel duty from rising, ensure older middle and upper classes do not feel they are paying more tax, and do nothing to threaten property prices. But this tried and tested formula no longer works as it once did.

Rishi Sunak is chancellor of a government elected in 2019 on a platform of levelling up poorer parts of the UK, and many of the new Conservative MPs who represent these areas — formerly part of Labour’s “red wall†of seats in northern English towns — have a very different agenda.

Miriam Cates, Tory MP for Penistone and Stocksbridge, a constituency just outside Sheffield which the Conservatives won for the first time in 2019, is an example of the new intake that wants to use the tax system to help poorer parts of the UK.

She recently put her name on a report by the Onward think-tank, which bills itself as “a powerful ideas factory for centre-right thinkers and leadersâ€. The report complains that value added tax receipts in the North East, one of the poorest regions, are double the level of London as a share of regional gross domestic product and calls for lower council tax for the cheapest properties.

“If we only look at spending and not tax, there is a risk we are trying to level up with one hand tied behind our backs,†says Cates.

Influential thinkers on levelling up outside government agree and highlight the scale of the task. According to Diane Coyle, professor of public policy at Cambridge university: “At a minimum the government will need to give all parts of the country a sense of momentum, of expanding opportunities.â€

With these views and the Conservative manifesto in mind, Sunak has already launched a bewildering series of initiatives to demonstrate the government is serious about putting “place†at the heart of policy.

In his December spending review, the chancellor tweaked the Treasury’s “green book†so that government investment appraisal no longer seeks to maximise the benefits from government projects, but also takes levelling up regional imbalances into account. He also established a £4.8bn “levelling up†fund for local investment projects that will have “a visible impact on people and their communitiesâ€. That came on top of the already established Towns Fund and the Shared Prosperity Fund for former industrial areas, deprived towns and coastal communities.

With the Covid-19 pandemic still raging, this Budget is not the time for big new commitments to further regional rebalancing, but the importance of the policy issue raises questions over the scale of UK regional disparities, the effect of the pandemic on them and how public spending money and tax bills are distributed around the country. It raises the questions — how much do some regions subsidise others, and how is this likely to change?

Regional prosperity and the pandemic

Boris Johnson caught the public mood when he put levelling up the UK’s nations and regions at the heart of his 2019 election strategy. A new public attitude survey shows little consensus in Britain on the need to tackle inequalities in income, wealth, race or gender, but there was one exception to this national disagreement. As Professor Bobby Duffy, director of the Policy Institute at King’s College London, explains, the public agreed “on the need to prioritise inequalities between deprived and better-off areasâ€, which was the top concern not just of those in the North of England. “All groups prioritise geographical inequality,†says Duffy. “This is rare.â€

But just as the government has never defined what levelling up actually means, regional imbalances are much more complicated than the headline statement that they are the worst in Europe.

Once incomes are taxed, pensions and social security benefits are paid and account is taken of increased housing costs in London and the South East, regional imbalances in average household living standards are much reduced, with median living standards in London no higher than the national average.

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, says earnings levels across the UK are also very similar once account is taken of the higher proportion of graduates living in London and the South East. “London is just chock-full of graduates,†Johnson says, adding that it therefore has many more people who have high incomes.

If levelling up was already more complicated than raising living standards to London’s levels because the capital’s streets are not paved with gold, a further problem arises from coronavirus. All the evidence from employment, furlough and benefit claims so far suggests London has been hardest hit in the pandemic during 2020. Torsten Bell, director of the Resolution Foundation, says: “We’ve got levelling down happening. London’s had the worst of the crisis.†London had the highest increase in universal credit claims during the pandemic and, according to the Department for Work and Pensions, it now has the highest proportion of people on UC of any British nation or region which, according to the IFS, has complicated the levelling up agenda.

Even with the increase in deprivation and hardship in London and the South East, there have also been big drops in employment across northern English cities, leaving more people there behind the national averages of employment and pay and claiming unemployment-related benefits. The Centre for Cities calculated this year that the levelling up challenge was four times harder than before the pandemic in terms of people in northern cities that needed better opportunities. “Birmingham, Hull and Blackpool in particular are the places with the biggest levelling up challenges,†it found.

Taxes and spending at regional level

With Sunak determined to demonstrate he can make progress in levelling up the country, the Treasury is under pressure to show that it is redistributing resources and opportunities from London and the South East to other parts of the UK.

One option would be a straightforward U-turn of the past decade of austerity, where local authority budgets took the largest hit of any area of government, and metropolitan authorities in the north of England along with London’s local authorities faced the sharpest cuts. But with politicians wary of such reversals, Tory thinkers are beginning to look elsewhere to redistribute regionally.

The report by Onward says the government must do more than just create funds to spend in areas that have fallen behind and instead look at the tax system. This, it adds, is not fair because London not only receives more in spending per head on research and development and transport, but also pays a lower share of GDP in tax than other regions. The capital contributes 33 per cent of its regional GDP, while the equivalent rate is 40 per cent in the North East, East Midlands and the South West, mostly because much of the income, for example from pensions, in areas outside the capital is not counted in GDP.

Will Tanner, director of Onward, calls for the use of the tax system to drive regional growth in poorer areas. “If levelling up is to succeed, we need to use the tax system to drive regional growth,†Tanner says.

One problem for Tanner and the new intake of Tory MPs in former Labour areas, however, is that the official data, when examined in the round, does not suggest London gets a good deal from the tax and public spending compared with other areas.

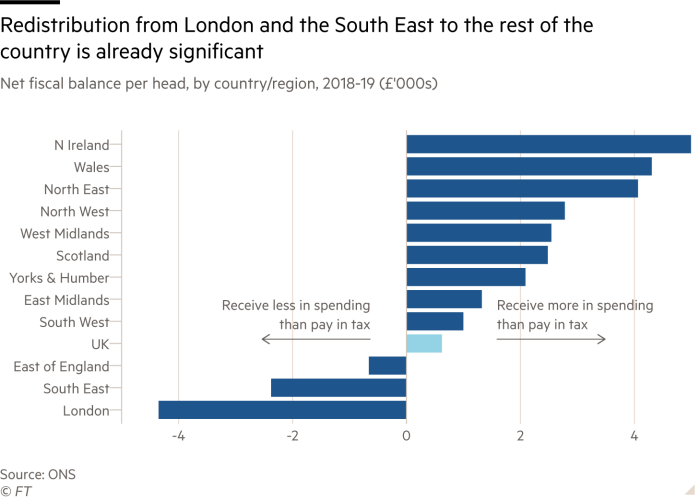

Office for National Statistics figures show that in the most recent data, Londoners on average received £4,350 less in public spending than they paid in tax in 2018-19. Alongside the South East, the capital was the only area to record the equivalent of a significant public finance surplus. Regions such as the North East received more than £4,000 more in public spending per head than was paid in tax, while the equivalent figure for Northern Ireland was almost £5,000.

Net tax payments from London to other regions have doubled since the financial crisis, while net receipts have risen especially fast in the North East of England and Scotland over the past decade.

Some of this, according to Johnson at the IFS, is the result of direct decisions by government to help poorer areas. “We still give a lot more per head to Liverpool than Brighton and more to schools in poorer areas than in richer ones,†he says.

But most of this redistribution from London and the South East is indirect and results from a progressive income tax system and welfare benefits that go to those with little other income — pensioners and those out of work, who predominantly live away from the capital.

The UK government redistributes heavily from richer to poorer people through the tax and benefit system as well as across people’s lifetimes so that they receive net support from the state as children and pensioners, but pay in while they are of working age. “The regional outcome is largely a byproduct of national considerations on health, education and pensions,†says Bell.

What this means for levelling up

Simply adding to regional redistribution from London to the rest of the country is generally poorly received by those who support the levelling up ambition because it would do little to attract the higher earners and working people that contribute more in tax than they receive in public spending.

Tony Travers, professor of government at the London School of Economics, says there is generally too much time spent examining and complaining about the levels of public spending in London compared with other regions. “We don’t spend enough time thinking about why the private sector is so successful in London and the South East, but obsess about public spending and redistribution,†he says.

This thinking suggests the government should create fewer levelling up funds for quick wins to gentrify town centres outside London and the South East, and not seek to harm the parts of the country with a thriving private sector, but instead try to establish some successful regional economies away from the capital.

“Potholes return, flowers wilt, and high streets face new challenges in a changing world,†says Tom Forth, head of data at the non-profit Open Data Institute Leeds. “Without a strong economy and the ability to raise taxes locally, a place cannot finance this spending by itself.â€

His international data work suggests the large northern cities are the best hope of generating dynamic smaller cities in the UK to rival Dresden, Lyon or Barcelona, rather than a scattergun approach to redistributing more funds from London to other parts of the UK.

“The problem for a national government is that the success of this strategy will take decades to become obvious,†says Forth. “And without a clear vision and strong leadership, people will struggle to wait.â€

[ad_2]

Source link