[ad_1]

In his first speech as prime minister, Boris Johnson pledged to answer “the plea of the forgotten people and the left-behind townsâ€. Few would have guessed that, just two years later, they would count among their number the affluent market town of Richmond in the North Yorkshire countryside but not deprived Barnsley in the former South Yorkshire coalfields.

The combined shocks of the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump in 2016, drew attention to so-called left-behind communities. Many traditionally leftwing working-class voters sided with Conservatives in what was taken as a backlash against globalisation and liberal economics. These often former industrial areas missed out on the economic growth that accompanied globalisation and were alienated by the social changes it brought. In response, their residents voted for those who promised to bring back the good times.Â

Britain’s recent attempts to make good on that promise have been mired in controversy, however. Critics accuse the government of using the money to level up the Conservative party’s electoral prospects rather than the economic realities of “left behind†communities. The government should first publish the methodology behind the allocation and then change how Whitehall makes these spending decisions.Â

Out of 45 areas allocated money from a pre-existing £3.6bn “towns fund†by the chancellor Rishi Sunak on Wednesday, 40 have Conservative MPs; five are represented by cabinet ministers. Meanwhile, the local authorities placed in the highest priority for a new “levelling-up fund†included affluent Conservative-represented areas like Richmond, while deprived communities such as Salford in Manchester and the former steel city of Sheffield were given lower priority.

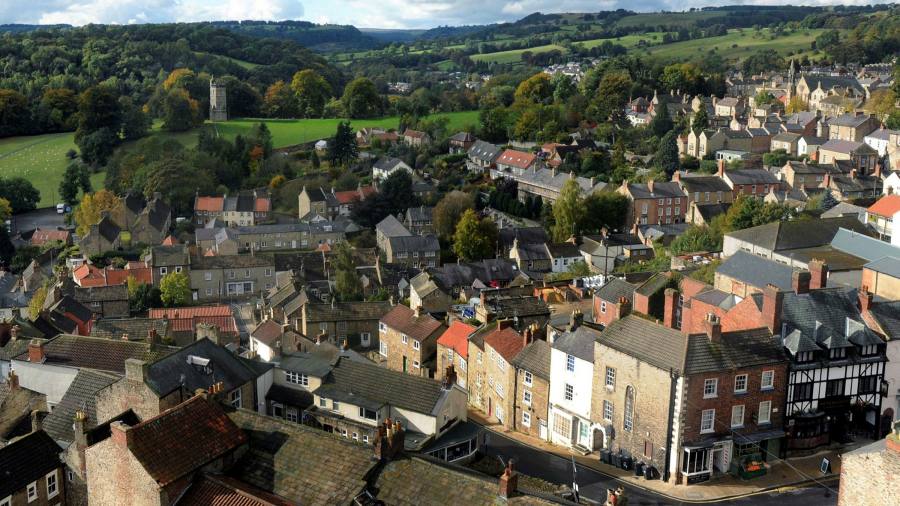

There may be a reasonable explanation: rural areas — where Conservative MPs predominate — may be prioritised as they lack transport links and are far away from essential government services, such as doctors. If this is true this methodology is flawed. While there are pockets of poverty everywhere, many of those living in beauty spots like Richmond — on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales — do so by choice and have the means to relocate if they wish. It can be a luxury to live far from the madding crowd.Â

Neither is this the first occasion when observers have raised concerns about the government’s approach. Last year, the National Audit Office said that the choice in 2019 of which towns could access the “towns fund†were based on “sweeping assumptions†and may have been politically motivated; a number were marginal constituencies. Many economists, too, have asked whether the decision to locate a Treasury North campus in Darlington — rather than alongside a new national infrastructure bank in Leeds — is because the North East town is close to Sunak’s constituency and part of the Tees Valley mayoralty, where the incumbent Conservative mayor is facing re-election in May.Â

Publishing the full methodology behind these decisions would clarify why they are made, and allow them to be properly scrutinised. Ultimately, however, the problem goes deeper. Whatever shock Brexit delivered, Britain retains a top-down approach to rejuvenating these “forgotten towns†that involves Whitehall choosing between different proposals and towns competing for a fixed pot of funding. A bottom-up approach that relocates decision-making would be better. If the Johnson government really wants to answer the “pleas of the left behind towns†it should start by listening.

[ad_2]

Source link