[ad_1]

When Johnathan Rodrigues came down with a headache and lost his sense of taste and smell, he felt sure it could not be Covid-19, having only recovered from the illness less than six months ago.

“Now I’m reinfected,†said the 26-year-old resident of the Amazonian city of Porto Velho. “I didn’t believe it when the result came out. I thought I was immune.â€

A grim sense of déjà vu is descending across Latin America’s largest nation, which is in the throes of a second onslaught of coronavirus even more intense than the first.

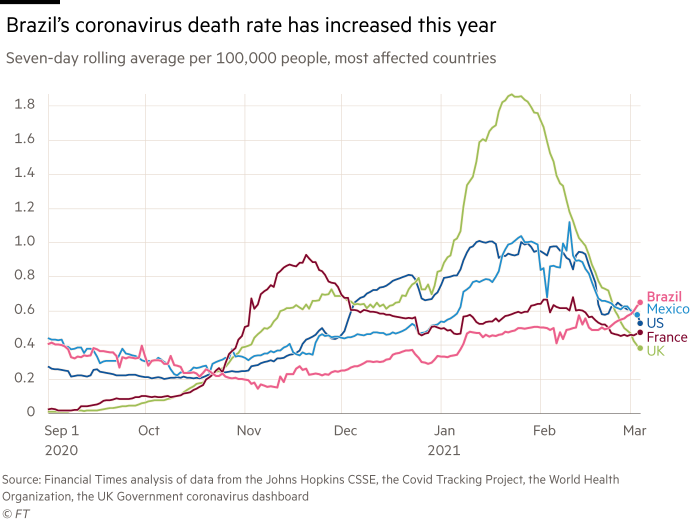

Daily fatalities in Brazil hit a record level of 1,910 last week, as infections climb and intensive care wards in many states reach bursting point. The country’s seven-day average of reported deaths, compiled from the data of state health departments, is about 30 per cent higher than a peak in July during the first wave.

Scientists and healthcare professionals believe one factor behind the resurgent outbreak is the more contagious P.1 strain, which, according to a preprint study released last week, may be able to evade the natural immunity developed by people who have already contracted the virus.Â

More than 260,000 people have lost their lives to Covid-19 in Brazil, the second-highest in the world behind only the US. In per capita terms it ranks 22nd, behind many European nations.

“After everything we went through in the first wave, with the optimism from the start of vaccinations it seemed we were beginning to get out of the pandemic,†said José Eduardo Levi, a research co-ordinator at medical diagnostics company Dasa and researcher at the University of São Paulo.

“Now we’re seeing a violent upsurge, with the biggest numbers since the beginning.â€

Experts also point to lack of preventive measures and issues in the rollout of immunisations, which critics have blamed on mismanagement by President Jair Bolsonaro’s government, as contributing to the deteriorating situation.

Throughout the pandemic, the rightwing populist president has diminished the severity of the virus, sworn not to have a jab himself after recuperating from Covid-19 and questioned the use of masks.Â

“Enough fussing and whining. How much longer will the crying go on?â€Â Bolsonaro said at an event on Thursday. “How much longer will you stay at home and close everything? No one can stand it any more. We regret the deaths, again, but we need a solution.â€

Luiz Henrique Mandetta — a former health minister who was fired by Bolsonaro last year after they publicly clashed over how to handle the pandemic — said the current predicament was the result of “mistaken political decisionsâ€.

“The ministry of health has been dismantled and a military man†— general Eduardo Pazuello, the incumbent health minister — “was appointed who has no credibility to be able to make the population understand its own role in reducing transmissionâ€, he added.

The world’s focus is now back on Brazil because of worries over the P.1 lineage of Sars-Cov-2 — linked to an explosion of cases in the rainforest city of Manaus and now detected in at least 25 countries — which the same scientific study found was about twice as transmissible as some other strains. A separate preprint paper suggested a China-made vaccine being deployed in Brazil might be less effective at preventing it.

“Other countries are concerned with Brazil, because it has no control strategy,†said Ethel Maciel, an epidemiologist and professor at the Federal University of EspÃrito Santo. “What is the plan? We don’t have a plan.â€

After emerging late in 2020, the mutant P.1 variant quickly became the dominant strain in Amazonas state, according to researchers. This coincided with a sharp increase of infections in Manaus, whose hospital system was overwhelmed earlier this year.

The episode undermined the idea that the population in Brazil’s jungle capital, three-quarters of whom were estimated to have been infected with coronavirus by October, might have attained herd immunity.Â

While the precise national frequency of P.1 is not known, public health experts say it has combined with a widespread failure to observe social distancing in Brazil to fuel the latest surge.

Over the Christmas season many families congregated throughout the country, while scenes of illicit parties were captured in cities such as Rio de Janeiro during the mostly cancelled Carnival period.

“The situation in Brazil is particularly tragic because the P. 1 variant emerged and shortly afterwards came the holidays and it took advantage of the moment to spread,†said Levi.Â

Another source of frustration is the pace of a nationwide inoculation programme. Following a delayed start, Brazil has delivered at least a single dose to 8.1m people, or 3.8 per cent of its population of 213m, according to a local media consortium. But dwindling stocks forced some municipal authorities to temporarily scale back injections last month.Â

“The big problem is a lack of vaccines,†said Adele Benzaken, a doctor in Manaus and medical director for global programmes at Aids Healthcare Foundation.

The government hopes to turbocharge the campaign with new supply contracts and increased domestic production. In the meantime, however, there is no indication that a leader who has prioritised keeping the economy open will change tack and tighten curbs.

An association of state health secretaries last week wrote an open letter calling for a night-time curfew, while a number of authorities, including in São Paulo, the continent’s most populous city, are implementing various degrees of lockdowns.

Thiago Vidal, a political analyst at consultancy Prospectiva, said there was little public appetite for more restrictive measures.

“Bolsonaro is not going to change,†he added. “His modus operandi is what it is. If he changes [his position], it will be a recognition that he was wrong.â€

With the government trying to push through a scaled-down version of an emergency coronavirus benefit that proved popular last year, Bolsonaro is banking on another boost to his ratings ahead of presidential elections in 2022, say analysts.

Brazil’s Senate on Thursday voted to support a fresh aid package worth R$44bn ($7bn). The proposal — which must still be approved by the lower house — is expected to include four monthly cash transfers of about R$250 to the nation’s poorest.

“Bolsonaro is looking for a free pass to put money into the economy in the hope that it will see him through in terms of his popularity. That worked for him in the past,†said MatÃas Spektor of the Fundação Getúlio Vargas think-tank.

“As long as the money keeps flowing the strategy stands a fairly decent chance of working again. The problem is how long can he keep pumping up the economy.â€

He added: “Brazil loses about 60,000 people to homicides every year and 70,000 die in car accidents on poor roads. There is a tolerance in a country like this for death.â€

Additional reporting by Carolina Pulice

[ad_2]

Source link