[ad_1]

It was not a given that the heirs of Shaka, the 19th-century king of the Zulu kingdom, would survive the long arc of colonial rule, apartheid and the turmoil of South Africa’s democratic transition to endure as one of seven officially recognised monarchies in the modern republic.Â

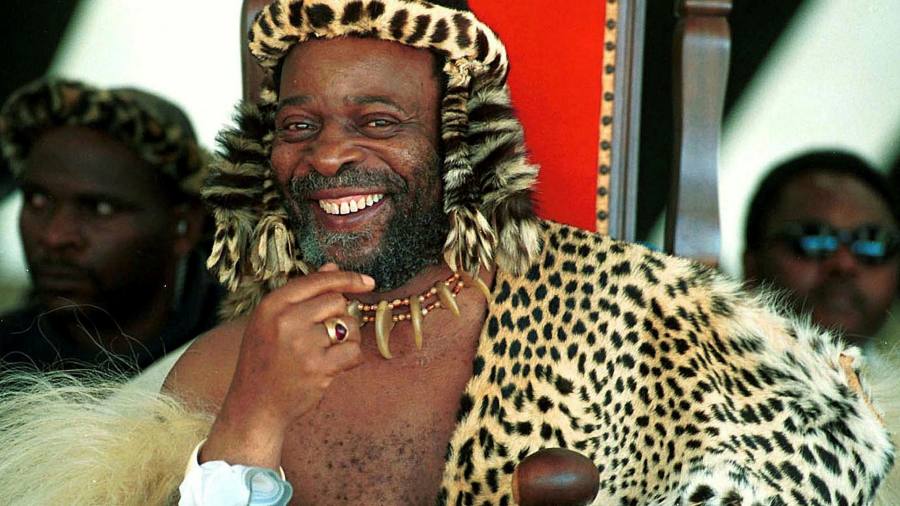

That King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu reigned for half a century, longest of any of the eight kings descended from the great Zulu monarch, reflects a political balancing act that gave a role to traditional chiefs inside the world’s most progressive constitution.

The king, who died at the age of 72 last week, counted nearly a fifth of South Africans as his subjects, his household drew upon state stipends that in 2020-21 were worth R71m ($4.8m) and he was sole trustee of the Ingonyama Trust, which manages about a third of all land in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

“History will recall that after many years of conflict and turmoil, it was in the course of his reign that the Zulu kingdom achieved the stability and harmony that had so long eluded it,†President Cyril Ramaphosa said this week in a eulogy for the king.

But for many South Africans, Zwelithini’s early years navigating apartheid oppression cannot be ignored, nor can a scandal over the Ingonyama Trust, which faces claims of unlawfully extracting rent, dispossessing women in particular. After the king’s death, one editor struck a nerve when he wrote that Zwelithini had been “a useful idiot in the hands of the apartheid governmentâ€. The royal household dismissed this as “vulgar languageâ€, but the shadows of South Africa’s past hang heavy over the king’s legacy.

Born in July 1948, just after fateful elections that handed power to the architects of apartheid in the National party, Zwelithini was prepared for the kingship from an early age. He succeeded his father, King Cyprian Bhekuzulu kaSolomon, in 1968 and, when crowned in 1971, it was as a figurehead for the Kwazulu “Traditional Authorityâ€, part of the white minority rule system of black “homeland†states. His authority was circumscribed, and he ruled with the Machiavellian Mangosuthu Buthelezi, his prime minister, relative and real power in the state. At the age of 92, Buthelezi led the king’s mourners.Â

As apartheid began to crumble, the king backed Buthelezi as his Inkatha party pushed Zulu interests on the national stage. It broke with the African National Congress and other movements in a rift that became a bloody civil war in the 1980s and 1990s. The king was an important voice for peace but his position was also a point of contention in the transition talks. It led to the 1996 constitution incorporating traditional leaders, and the Ingonyama Trust.

With the advent of democracy, the king, often clad in the traditional leopard skin of royalty, turned to the cultural revival of his people in a bid to reconcile tradition with modernity in the new South Africa. He restored the annual reed dance of Zulu maidens at his palace and revived the “first fruits†festival when warriors kill a bull with their bare hands.

But what the king said at these gatherings often exposed darker undercurrents of post-apartheid democracy. In 2015 he appeared to tell foreign nationals to “pack their bags and go home†as South Africa exploded into xenophobic riots. The king blamed mistranslation; spokespeople said that he had been referring to illegal immigrants.

Jacob Zuma, the self-proclaimed “100 per cent Zulu†president, often played up his association with the king. But Zwelithini was outraged by political killings that engulfed KwaZulu-Natal as the ANC decayed into disputes over patronage. He called them criminal rather than political. Yet the killing goes on today.

So too do the alleged abuses of the Ingonyama Trust, currently subject to a lawsuit and calls for its repeal. It denies any wrongdoing. Zwelithini equated criticism of the trust with attacks on his royal person. “The king’s enemies have shown themselves very clearly by saying we must be stripped of our blanket, which is the land of our ancestors,†he said in 2019.

The king had six wives and 28 children. Misuzulu Zulu, his oldest surviving son, is considered his likeliest successor. With legal battles over the trust and disaffection over rural poverty in the former homelands, the bonds Zwelithini forged between traditional leaders and a young democracy will be tested like never before. The leopard skin will not lie easy on the ninth successor to Shaka.

[ad_2]

Source link