[ad_1]

The statement from Brazil’s defence ministry was a compact two sentences, but it detonated with the explosive power of a bomb.

In the tersest of prose, it announced that the heads of the army, the navy and the air force “had been substituted†on March 30. The departure of the senior military leaders, in protest at the sacking of the defence minister the previous day, marked a dramatic break between far-right president Jair Bolsonaro and the institution he had sought to cultivate so assiduously.

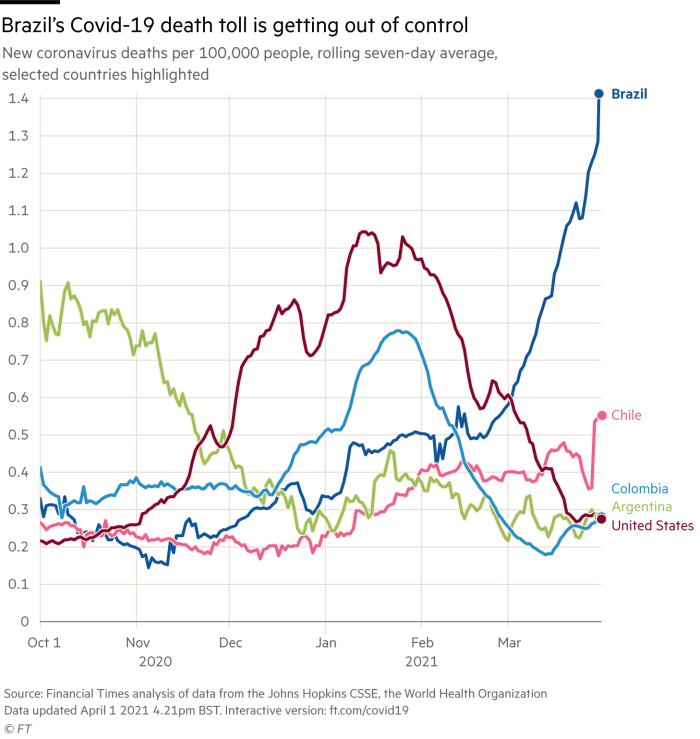

The generals’ sudden exit comes amid a public health disaster, with record death tolls from coronavirus turning Brazil into the global epicentre of the pandemic. The move has deepened the political crisis over Bolsonaro’s stubborn opposition to lockdowns, and the mercurial former army captain’s threats to use the military against local officials who tried to impose them.

“In the history of the republic, there has never been a decision by the three commanders to resign at the same time, much less in protest against the president,†says Carlos Fico, professor of military studies at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “There was never a crisis of these dimensions beforeâ€.

The armed forces are not the only institution losing patience with Bolsonaro. A week earlier, hundreds of prominent business leaders signed a manifesto demanding effective government action to control the fast-worsening second wave of the pandemic, which threatens Brazil’s stuttering economic recovery.

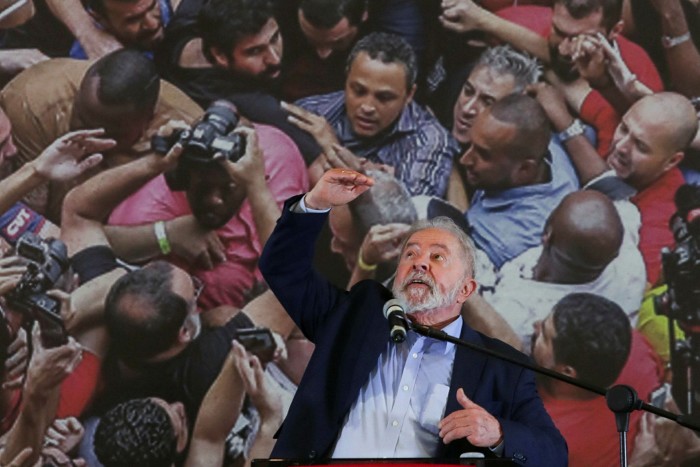

In Congress, there are the first murmurings of a potential effort to impeach the president. And with the return of leftist former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to politics after his conviction for corruption was overturned, Bolsonaro is no longer the favourite in next year’s elections.

One of the world’s leading coronavirus sceptics, Bolsonaro has for most of the past year refused to wear a mask, criticised vaccinations and dismissed the pandemic as “a little fluâ€. He is now struggling to keep his government together and his re-election hopes alive amid some of the world’s worst Covid-19 numbers.

“Bolsonaro is now more isolated than ever,†says Mario Marconini, a managing director at the consultancy Teneo. “As the pandemic inevitably worsens, there will be another reckoning by Congress in the not so distant future to see whether he has become more disposable than he is now.â€

‘There was never social distancing’

“Last year, they did not die the way they did this month. This year is much worse, even with the vaccine,â€Â says Jadna Batista Pereira, a 51-year-old nurse at a public hospital in São Paulo

Pereira is exhausted, angry and suffering symptoms of coronavirus despite having been vaccinated. “My entire hospital is dealing with Covid. We have three ICUs and they are all 100 per cent full,†she adds.

Brazil is regularly reporting more than 80,000 new coronavirus cases every day, the world’s highest number of infections. More than 325,000 people have died as the country suffers a new wave of disease far worse than last year’s.Â

The crisis has exposed what experts say are disastrous errors by Bolsonaro in his handling of the pandemic. The consequences are being felt well beyond Brazil’s borders.

The Pan-American Health Organisation reported last week that the P. 1 variant driving the second wave in Brazil had been found in 15 nations across the Americas. “Unfortunately, the dire situation in Brazil is also affecting neighbouring countries,†says Carissa Etienne, PAHO’s director.Â

Senior members of Congress who had supported the president are having second thoughts. Arthur Lira, the speaker of the lower house, issued a “yellow warning†to the government last week and for the first time hinted at the possibility of impeaching the president.

Always a polarising figure, Bolsonaro, 66, has made himself a particular target because of his views on coronavirus. Like the former US president and his political soulmate Donald Trump, he constantly played down the virus, telling Brazilians to “take it like a manâ€.

His stance appalled medical professionals. Yet, in a large emerging market economy where financial resources to underwrite lockdowns are limited and poverty is acute, Bolsonaro’s insistence that shutting down the economy would be a greater evil struck a chord with some Brazilians.

An astute populist, the president greeted crowds of supporters maskless at the height of last year’s infections, buying a hot dog from a vendor to make his point about keeping the economy running. When he caught the virus himself last July, Bolsonaro assured his supporters that, thanks to his “history as an athleteâ€, he would recover quickly — and he did.

Deaths in Brazil hit a plateau in the middle of last year and gradually tailed off. Generous government support for the poorest third of society, dubbed “corona vouchersâ€, eased the financial pain.

Helped by the handouts, Brazil’s economy contracted 4.1 per cent last year, better than economists had feared. In the fourth quarter, gross domestic product rebounded. As deaths declined and the economy grew, Bolsonaro’s poll ratings rose. For a brief period, it looked as though his risky gamble might pay off.Â

But in November, infection rates started rising again. As deaths climbed steadily over the Brazilian summer, Bolsonaro stuck to virus scepticism. He repeatedly attacked a Chinese-developed jab and in December suggested the BioNTech/Pfizer shot might even turn people into crocodiles.

By carnival season in mid-February, Brazil’s death rates exceeded those of the first wave. Then they more than doubled again and, by late March, Brazil hit a new record of more than 3,000 deaths in a single day.

Felipe Naveca, a virologist at Fiocruz Amazônia, says Brazil “entered a vicious cycle [which] led to the rise of a more transmissible variantâ€. “The root cause was that there was never social distancing like there should have been in Brazil. And the worst consequence of all was P.1.â€

Yet in early March, as deaths approached 2,000 a day, Bolsonaro told Brazilians to “stop whining†and asked: “How long are you going to keep crying about it?â€

Bolsonaro’s opposition to lockdowns is only part of the problem. His denialism, communicated through numerous social media groups, is also influential.

Jamal Suleiman, an expert in infections at the Emilio Ribas Institute in São Paulo, is intensely angry about it. He complains that acquaintances keep asking whether scenes of oxygen shortages on television are real. “This weekend I received more than half a dozen videos from friends asking whether it was true or not,†he says.

The president’s handling of the pandemic forms part of his dispute with the military leadership. Three times last month, Bolsonaro invoked what he called “my army†as an ally in his battle against lockdowns, alarming military leaders who did not wish to be drawn into partisan pandemic politics. “My army won’t go into the streets to force people to stay at home,†he said on March 8.

General Fernando Azevedo e Silva, the defence minister fired by Bolsonaro three weeks later, pointedly referred in his departure letter to the fact that he had “preserved the armed forces as institutions of the stateâ€.

‘A complete mess’

Through a field of freshly dug mounds of ochre soil, men wearing white protective overalls, breathing masks and gloves carry a coffin to one of dozens of empty burial plots.

Row upon row of graves are slowly being filled in Latin America’s largest cemetery in the east of São Paulo, where mechanical excavators turn over earth in anticipation of new arrivals.Â

In normal times there would be 35 to 40 burials a day, says a gravedigger taking shelter from the tropical sun under a tree; now there are 80 to 90.

Scientists are still studying the P. 1 variant, which emerged in the Amazon last December. Most agree that it is significantly more transmissible and can reinfect some people who already had the virus. One non-peer reviewed paper by a UK-Brazilian team of researchers found it was between 1.4 and 2.2 times more transmissible.Â

The contagiousness of P. 1 was shown graphically in Manaus at the start of the year, when there was an explosion of Covid-19 cases in the Amazonian city four times higher than last year’s peak.

“The majority of health professionals believe that it’s a different and more serious illness . . . with a worse prognosis in young people,†says José Eduardo Levi, a researcher at the University of São Paulo. “My opinion is that it’s more pathogenic, more fatal.â€

The rapid spread of P. 1 has swamped Brazil’s health system. Domingos Alves, professor at the Health Intelligence Laboratory at the University of São Paulo, says accurate forecasting is now impossible because of the lack of hospital beds. “The possibility of reaching 5,000 deaths a day is very great,†he adds.

Faced with the unfolding health disaster, Brazil’s options are limited. Vaccinations have been slow to get under way, despite the country’s well-respected public health system. By March 27, just over 7 per cent of the population had received at least one dose of a vaccine, a higher proportion than Russia or India but well behind Turkey or Chile.

Critics blame disorganisation inside the health ministry, which is now on its fourth minister since the start of the pandemic. “There was a complete lack of planning,†says Monica de Bolle, a Brazil expert at the Peterson Institute in Washington. “In December, they started to think about a vaccination campaign but they didn’t even have enough syringes. It was a complete mess.â€

The health ministry now says it has contracted 562m doses of vaccine for delivery this year — more than enough to give two shots to all of Brazil’s 213m population — but this is dependent on local production which has yet to start.

‘Close to collapse’

Brazilians remain divided over lockdowns and their effectiveness is limited by the need of poorer families to go out to earn a living. More generous welfare payments would solve that but, as Bolsonaro acknowledged at the start of the year, “Brazil is brokeâ€. Government debt is hovering around 90 per cent of GDP, a high level for an emerging market.

Making matters worse, inflation has started to take off. Prices rose 5.2 per cent in February, triggering anger among those struggling to survive. Maria Izabel de Jesus, a retired 72-year-old who lives in the east zone of São Paulo’s, says food had become unaffordable. “It’s too much. You can’t buy anything,†she said.

Graffiti have appeared on walls denouncing “Bolsocaroâ€, a play on words using the president’s name and the Portuguese word for “expensiveâ€. Worsening expectations on inflation forced the central bank to raise interest rates from historic lows this month and it warned of further increases to come.

The surge in coronavirus cases is forcing economists to downgrade forecasts. Cassiana Fernández, chief Brazil economist at JPMorgan, sees a contraction of 5.5 per cent in GDP in the first quarter, followed by a weak recovery of 1.5 per cent in the second quarter. “The next month will be especially challenging,†she says. “We have the risk of a more disruptive scenario . . . We are very close to seeing the public and private health system in major cities collapseâ€.

Faced with a deteriorating economy, a health crisis of global proportions and a bid for re-election next year, Bolsonaro received another blow last month: Lula, Brazil’s most famous politician, was free to run again for office after a supreme court judge quashed his corruption convictions.

Although unpopular with some Brazilians because of the corruption scandals which dogged his governments, Lula has a better chance of defeating Bolsonaro than anyone else in next October’s presidential vote, according to opinion polls.

The country’s business elite, traditionally hostile to Lula, is starting to believe that the former trade union leader is the lesser evil. MaÃlson da Nóbrega, a former finance minister, says: “I see many people saying that if the situation is between Bolsonaro and Lula, that they would hold their nose and vote for Lula.â€

Bolsonaro’s supporters, however, are not giving up. “The re-emergence of Lula on the scene, tragic as that is, has made this government up its game,†says one financier who is close to the president’s camp. “Bolsonaro is consistently underestimatedâ€.

Under pressure from the spiralling death toll and the impending election, Brazil’s president has shown some tentative signs of changing tack.

From time to time, he now wears a mask in public. Last week he addressed the nation on television talking about vaccinations. He finally convened a national task force against coronavirus and spoke in more conciliatory tones.

“Bolsonaro absolutely mishandled the pandemic, in every possible way†says Matias Spektor, associate professor at the Fundação Getulio Vargas. “Now he is beginning to reverse, to use a different tune. The reason is the absolutely shocking collapse of the health system across Brazil, plus the appearance of Lula.â€

Bolsonaro also needs to shore up support to stave off the risk of impeachment. The reshuffle this week which switched the defence minister also handed a key cabinet post to a member of the Centrão, a non-ideological political bloc which backs the president in return for extra spending. “They don’t need him but they know he needs them,†says de Bolle.

The president’s threats of using the army in support of his controversial policies — or even in a Trump-style effort to cling to office after a disputed election next year — now look increasingly unlikely in the wake of the generals’ public insistence on sticking to their constitutional role, although Bolsonaro could still try to appeal directly to the military rank-and-file, where he remains popular.

But it is not clear yet whether Bolsonaro’s belated efforts to step up vaccinations and halt the spread of the virus can contain the deaths and stop transmission of the P. 1 variant, which threatens populations everywhere.

“The world needs to realise the risk that Brazil represents today to the global population,†says Levi at São Paulo university. “There are only two ways to combat this: social isolation and mass rapid vaccination.â€

Additional reporting by Carolina Pulice in São Paulo

[ad_2]

Source link