[ad_1]

Every day at abattoirs across Brazil, tens of thousands of cattle are butchered into choice cuts, burgers and ready-meals sold at home and around the world.

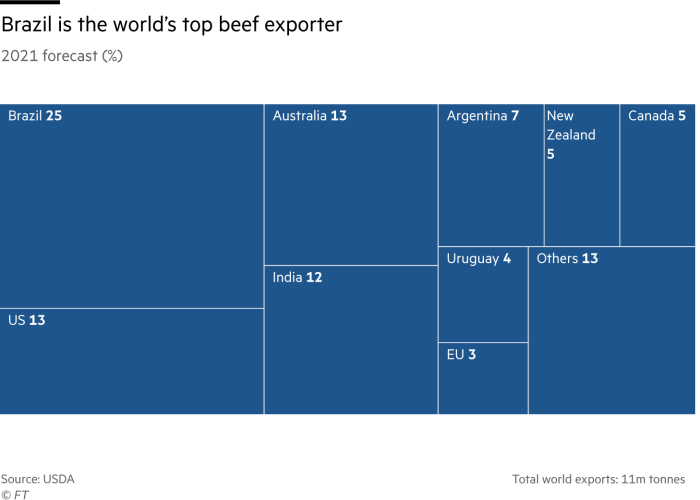

While the booming multibillion-dollar trade has made the Latin American nation the biggest global exporter of beef, the exact origins of the animals are often a mystery.

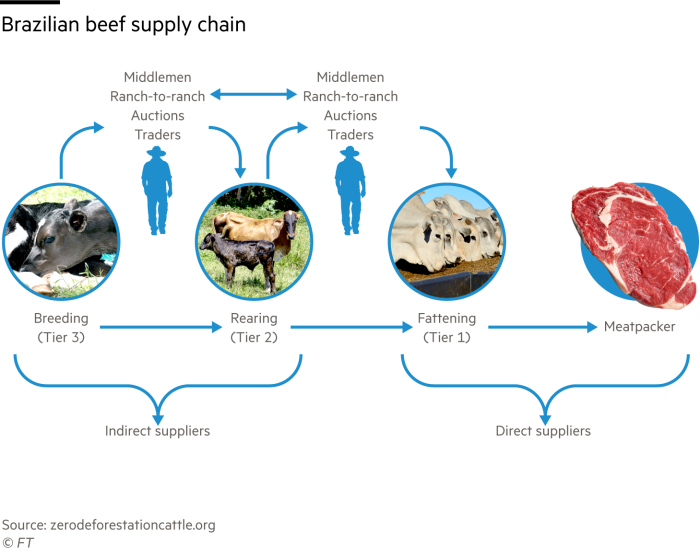

“There is a guy who produces the calf, one raises it and another that does the fattening,†said Gilberto Tomazoni, chief executive of JBS, the world’s largest meat processor with $50bn in annual turnover. “Basically, there has been a lack of information to monitor the suppliers of our suppliers.â€

The São Paulo-headquartered group, which earlier this month suffered a cyber attack on its North American and Australian systems, has long been accused of links to ecological damage. But it is now embarking on a sweeping sustainability drive as Brazil faces threats of divestment and product boycotts over the Amazon rainforest.

At its vast industrial complex in Lins, in the interior of São Paulo state, JBS touts initiatives such as the recycling of plastic waste and renewable energy provided by a power station fed with sugarcane residue as evidence of its endeavours.

Yet as the country’s top meatpackers pledge to slash greenhouse gases, solving the puzzle of where their cattle come from will be vital for efforts to clean up an industry that is one of the driving forces of deforestation — and a significant contributor to global warming.

JBS recently set a target to be net zero by 2040, which will involve reducing its own and indirect emissions, then offsetting any that remain.

Its main rivals, Marfrig and Minerva Foods, are pursuing similar ambitions.

“Given how serious the situation is with deforestation in Brazil, this is quite timely,†said Kiran Aziz, senior analyst at KLP, Norway’s largest pension fund, which excluded JBS from its portfolio in 2018 due to corruption risk. “What’s more important is the implementation.â€

The trio agreed more than a decade ago to prove they were not buying animals, directly or indirectly, from farms engaged in deforestation in the Amazon. Given its capacity to absorb carbon dioxide, the rainforest is a bulwark against climate change.

Australia’s red meat and livestock industry is also aiming to reach carbon neutrality by the end of the decade, while the largest meat company in the US, Tyson Foods, is working to cut 30 per cent from greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

However, the majority of the world’s largest meat and dairy companies have not made explicit net zero undertakings, according to recent research by New York University.

After destruction of the Brazilian Amazon surged to a 12-year high in 2020, meatpackers there came under pressure to prove the pledges were not just a greenwashing exercise.

Inaction carries financial risk. The big three Brazilian groups rely on European investors and banks for at least a quarter of their funding, including debt financing and equity holdings, according to Chain Reaction Research.

“They face the risk of a backlash from European institutions, like the divestment from JBS by Nordea,†said Matthew Piotrowski, director of policy and research at Climate Advisers, referring to the Finland-based asset manager’s decision to dump the stock last year on environmental concerns and other issues.

Maria Lettini, director of the Fairr Initiative, an investment advisory and research network, said: “Overall, investors are quite supportive, but many are sceptical about how they are going to meet those net zero targets.â€

Although Brazil’s biggest beef processors have succeeded in monitoring direct cattle sellers, they have yet to implement full traceability of the scattered and sometimes small-scale ranches that feed into production chains and where animals can spend most of their lives.

While official paperwork is required for each stage of animal transit, the documentation is not public and privacy laws prevent third-party data being shared. When the different raising phases are not carried out on the same farm, this makes it difficult to trace provenance beyond the immediate seller.

“[The] complexity in livestock production here in Brazil is we have 2.5m producers with cattle, spread out in a big area around the country,†said Paulo Pianez, director of sustainability at Marfrig. “For each direct supplier, we can have 10 indirect suppliers.â€

Satellite imagery is already used as a tool for checking that direct providers are in compliance with rules against deforestation and encroachment on indigenous territories. JBS monitors 60,000 farms this way across an area 1.5 times the size of Germany and says it excludes any sellers found in breach.

Now the big task is to gain visibility further down the chain. JBS has developed a system based on blockchain to securely and confidentially track the certification of each head of cattle, so animals from illegally logged lands cannot be “laundered†through legitimate ranches supplying the group.

The data are then sent to an industry association for validation and the outcome is shared with the livestock seller. All direct suppliers in the Amazon must by 2025 sign up to the JBS digital ledger, which will be audited independently, or face exclusion.

Marfrig has identified the origins of 62 per cent of all its cattle from the Amazon and 47 per cent for the Cerrado savanna biome, including direct and indirect suppliers, and is recording the information through a blockchain-enabled platform.

For its part, Minerva claims to be the first meatpacker to have extended geospatial monitoring outside the Amazon, tracking direct suppliers in areas including the Cerrado, Atlantic forest and the marshy Pantanal region.

It is now integrating a traceability tool into its existing system in order to harvest greater information on risks around indirect suppliers in the Amazon.

Taciano Custódio, Minerva’s director of sustainability, said its analysis showed that most of the properties overlapping deforestation occurrences in the rainforest were relatively small in size. If they are cattle ranches, they would probably provide only a few animals each month.

“The deforestation challenge of Brazil is more than the environment — it’s linked with social development,†he added. “This is survival for these guys.â€

Yet even if deforestation were to be eliminated from Brazil’s beef industry, cattle rearing inherently results in large amounts of methane, a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2.

Approximately 70 per cent of all agricultural emissions in Brazil come from bovine digestion, as well as associated activities, according to Imaflora.

“It’s a lot, and if you add that to the emissions from deforestation to raise cattle it’s even bigger,†said project co-ordinator Isabel Garcia Drigo.

Researchers say possible solutions include more intensive farming methods to improve land productivity, along with shortening the lifespan of cattle, which tend to be longer than in the US or Canada. Another focus is animal feed, whether supplements or different kinds of grasses, to reduce methane belched by animals.

“The costs of changing the model are not trivial,†said Drigo. “If they [the meatpackers] put in a considerable amount of money to help producers to reduce their emissions, then yes, it’s possible.â€

JBS has allocated $1bn for decarbonisation investments over the next decade and Tomazoni points to “regenerative†agricultural projects that combine livestock with crops and reforestations, helping sequester carbon. JBS plans to spend $100m on R&D by 2030 to support this kind of farming.

The food conglomerate reported net income of R$4.6bn (US$860m) last year.

Minerva has allocated R$1.5bn for emissions reductions and Marfrig R$500m, mainly towards full cattle supply chain visibility by 2030. Last year the companies generated net income of R$697m and R$3.3bn, respectively.

Despite the increased scrutiny, some fear there may be insufficient commercial impetus for the meatpackers to act quickly.

For all the awareness of the climate emergency, global demand for beef has remained robust and cattle prices in Brazil have touched record levels. While Minerva’s stock is slightly down, the share prices of JBS and Marfrig have gained at least a quarter in 2021, outstripping the wider Brazilian market.

Activists criticise the sector’s commitments as too distant. JBS, for instance, has undertaken to end illegal logging in its Amazon supply chain by 2025, in other Brazilian biomes five years later — and finally zero deforestation globally by 2035.

As a seller’s market, producers may look to take their material elsewhere if they dislike a meatpacker’s conditions.

“It is naive to again trust more promises of an industry which at the very core . . . is an emissions producer,†said Daniela Montalto, a campaigner at Greenpeace. “We’re talking about land grabbers, ranches laundering illegal cattle into the supply chain of the slaughterhouses.â€

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

[ad_2]

Source link