[ad_1]

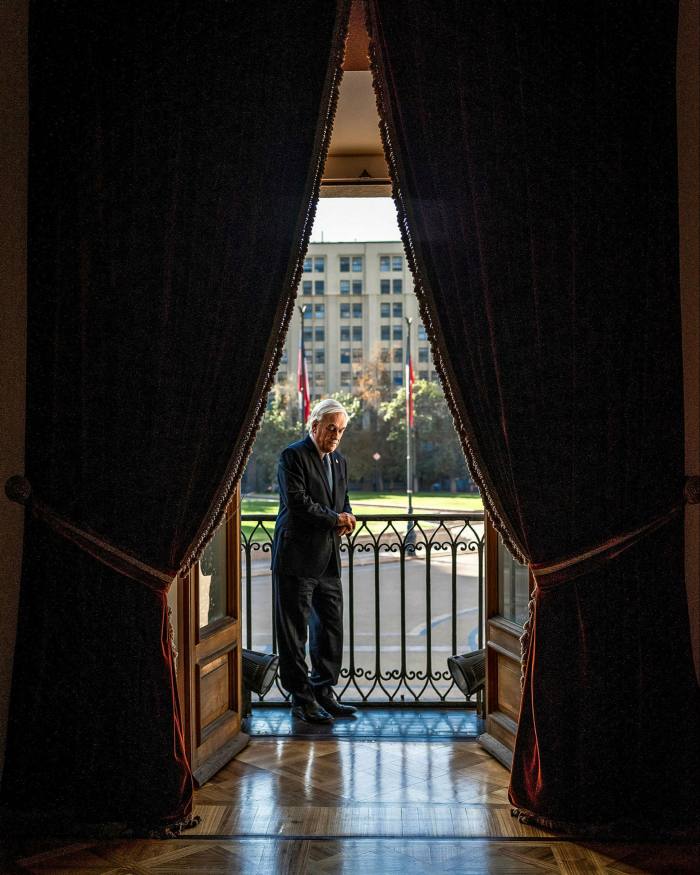

Sebastián Piñera is no stranger to adversity. Eleven days before the start of his first term as Chilean president in 2010, one of the strongest-recorded earthquakes devastated his country. Much of that presidency was spent picking up the pieces.

His second term in office, which he hoped would hasten Chile’s passage from middle-income status to fully developed nation, has instead been marked by a triple crisis: the coronavirus, a prolonged spell of riots and social protests in 2019, and last year’s global economic downturn.

“We aren’t here to complain or to cry over spilt milk,†Piñera says briskly in an interview with the Financial Times when asked about the multiple misfortunes. “We are here to deal with adversity, overcome it and carry onâ€.Â

Adversity was not much in evidence early in Piñera’s career. He made his first fortune by bringing credit cards to Chile in the 1970s. Then he made a shrewd early investment in LAN Chile, an airline which later became Latin America’s biggest airline LATAM. In the process, he became one of Chile’s richest men, with a fortune of nearly $3bn, according to Forbes.

Along the way, he acquired a reputation as a fearsome dealmaker. “You don’t want to be on the other side of the table from Piñera,†says one business figure in Santiago.Â

As a conservative billionaire and leading member of the elite, Piñera was an easy target for the street protesters of 2019, whose uprising was motivated partly by anger that the fruits of Chile’s strong economic growth had not been shared widely enough.

Piñera was criticised for a heavy handed initial response to the riots after he declared a state of emergency and sent the army on to the streets, saying Chile was “at war with a powerful enemyâ€. His poll ratings plunged to single digits and demonstrators called for his resignation.

“Of course, we have made mistakes,†Piñera admits, “but I think that, in the main, we have managed to direct the three big challenges on to the right pathâ€. The social protests have been channelled into a democratic process to elect members of a special convention to draft a new constitution; the pandemic has been fought with one of the world’s fastest vaccination programmes, plus Latin America’s most comprehensive testing regime; and the economy is forecast to recover its pandemic-related losses faster than any other in South America.

Still, the experience has been a severe test for the president, whose long experience in the private sector often influences his style of governing. “He’s the best CEO Chile could have but he’s a horrible politician,†says one banker in Santiago, echoing a commonly heard view that Piñera’s people skills are no match for his business acumen.

One former official, who knows him well, says of the president: “He is a very smart man and an able manager. But he is impossible to like.â€

With an energy that belies his 71 years, the Chilean leader wants to be remembered when he steps down next year for helping to bring his country intact through its most difficult period in half a century and laying the foundations for prosperity.

The goal of developed nation status, however, remains elusive. Near the start of his first term, Piñera told the Financial Times that he hoped it would be reached by 2020, yet a decade later he admits “we still have a long way to goâ€.

Andrés Velasco, a former finance minister under a centre-left government, criticises Piñera for failing to do enough to stimulate economic growth, saying that he relies excessively on a belief in “animal spiritsâ€. “If the big reason to vote for Piñera was to achieve a lasting increase in the rate of growth, he’s failed to deliver,†Velasco says.

Chile is still dependent on copper exports, although it has built up successful overseas sales of fresh fruit and wine and is pursuing investment in renewable energy and the production of green hydrogen.

The president points to how Covid-19 has accelerated technological change and says the digital economy is the place to look for prosperity. “When we return to a new normal, the world will be very different . . . †he says. “We can’t arrive late for the technological revolutionâ€.

To stay competitive, Chile is creating a nationwide fibre-optic network for broadband services and aims to be one of the first countries in the region to bring 5G mobile services online. With other South American nations, it is also investing in the continent’s first direct subsea optical cable link with east Asia and the Pacific, removing the need to route traffic via North America. Since 2000, trade with China has grown to the point where it is Chile’s largest trading partner. Piñera has no time for trade wars and wants the US to collaborate with Beijing rather than confront it. He will not pick sides over issues such as whether to use Chinese 5G technology. “Chile has good relations with China and good relations with the US,†he says. “It will hold auctions for 5G technology according to the interests of Chile, without us getting into this fight between the two big superpowers.â€

Mindful of protectionist sentiment among American Democrats, President Joe Biden said on the campaign trail he would not pursue fresh trade deals in office. Piñera nevertheless hopes that Washington will eventually return to pursuing the aim of negotiating a free trade area covering all of the Americas — a goal set by Bill Clinton in 1994 but abandoned a decade later.

With less than a year to go before he steps down, Piñera remains determined and energetic. A strong Catholic faith and a supportive family have helped him weather the storms, he says.

The earthquake in his first term destroyed a third of Chile’s schools and hospitals.

“Now we have to face adversities of a different kind,†he says. “And we are facing them with all our strength and will and with the best tools, within democracy, the rule of law and national unity.â€

Finance minister quietly optimistic on growth and pandemic recovery prospects

A new wave of the coronavirus, a fresh lockdown and a prolonged bout of political uncertainty might sound daunting but Rodrigo Cerda, the finance minister of Chile, is unfazed: the Pacific nation is likely to outperform an official forecast of 5Â per cent growth this year.

“I share with many people [the idea that] the bias will be to the upside,†Cerda, right, explains. “We are continuing to be conservative [in our forecasts]â€.Â

The IMF is even more bullish. it predicts an expansion of 6.2 per cent this year, which would erase last year’s pandemic-related fall in output. Oxford Economics believes Chile may grow by 7.5 per cent.

Higher prices for copper, Chile’s main export, have helped to fuel growth as well as a generous Covid support package, worth about 10 percentage points of GDP. Unlike most of its peers in emerging markets, Chile will have no problem paying for it. Cerda says the pandemic showed the value of Chile’s rainy-day funds. “For a long time, we have said to Chileans that we save in good times and that’s what we have done. In bad times our rule allows help for them.â€

Chile’s debt-to-GDP ratio is set to climb to 43 per cent by 2024 but, at that level, would still be the envy of many developed nations. Cerda believes those rainy-day funds show the value of Chile’s market-friendly economic model, despite the criticism it has received since the riots in 2019.

“When you look at the past 30, 40 years in Chile, we have seen a very significant fall in poverty rates, we have also seen Chileans who have increased their incomes very significantly,†the minister says. Another 30 to 40 years like that would allow the country to reach fully developed status.

[ad_2]

Source link