[ad_1]

The Electric Zine Maker software Nathalie Lawhead

When the pandemic hit, I decided to document the day-to-day life during this moment of turmoil and uncertainty as a grounding practice. I started making quarantine zines out of folded A4 sheets of paper, writing things like “I hate being scared of human contact, and I hate what this might mean for me long term†in black pen, attempting to give lockdown days some kind of coherent shape. This project soon dwindled as the very thought of creating something out of abject loneliness and desperation became too overwhelming.

After weeks of not having the energy to create anything, I came across a software called Electric Zine Maker on Twitter, a free, open source zine-making tool. I immediately downloaded and started playing with it. The feel of it is punk rock cuteness, and you can view your work just as if you were working on a folded A4 sheet of paper. I made another quarantine zine, and on one of the pages I inserted a photo I had taken on a night walk, and I wrote in bold white letters: “Does anyone feel like they should be more productive, because all we have now are these portals to each other which allow for infinite hustles but never equal a living wage?†and stamped the word HELP over and over again at the bottom of the page.Â

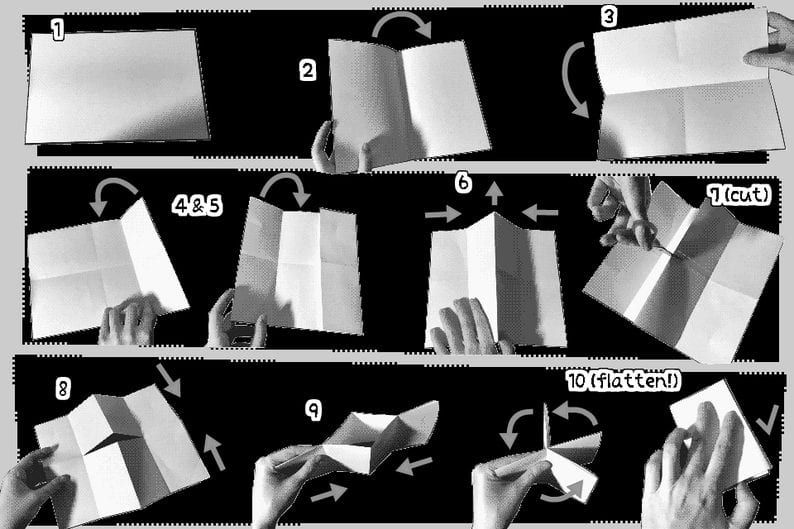

The creator of the tool that saved my creativity from pandemic rot is Nathalie Lawhead, a non-binary experimental software creator and artist based in Irvine, California. They started to build the tool as a simple page-fold template with black and white text capability, but the tool blew up on social media, with zinemakers asking for more features that would bring the software closer to the IRL zine-making experience.Â

“I got excited because people were excited so I kept building on it, and making more stuff,†Lawhead said in an interview with Observer. “And people are sending their requests for features and it’s a bigger thing now. It’s really cool to see how passionate people are about it and all the beautiful things they’re making, it’s really rewarding to work on it because of that.â€

The Electric Zine Maker expanded the possibilities for the zines I was making; I was able to upload my own photos and input them in into my zines, draw with different kinds of pens, apply filters to make it look more handmade and punk-y, and upload shapes to make stamps or even design my own stamps. The cutesy, silly, do-whatever-you-want atmosphere of the Maker gave way to goofier creations than my previous melodramatic ventings, notably men i am attracted to that exemplify my butch desire and things i love about oscar isaac hernández estrada.Â

This is true for other zine creators as well. The zines range from the personable-relatable (I HATE SEATTLE! A memoir of living in the northwest by Neffer LeMort, who tells Observer that the zine is a success because other people seem to hate Seattle too), to the hyper-personal (A Handful of Recurring Dreams by Jeremy Oduber, who says he loves this particular zine he made because “it’s simultaneously deeply personal and an attempt to connect with something universal.â€), to queer abstraction (Women I’d Go Straight For (with respect) and my self abstracted by Ardent Eliot : – ) Reinhard, otherwise known as trophyhusban on itch.io). Reinhard sees their zines as “a shift away from a quicker, rougher sort of aesthetic (which for the record is totally legitimate and something I am still interested in) towards a more sophisticated, polished kind of look.†The Zine Maker allows for creators to operate outside a capitalist market that prioritizes what sells and typifies aesthetics into perfection and precision.Â

A zine Women I’d Go Straight For by Ardent Eliot : – ) Reinhard made with Electric Zine Maker Ardent Eliot 🙂 Reinhard

“One way that the Electric Zine Maker has helped me with my art making is the imprecision of the program,†Reinhard told Observer. “It doesn’t let you snap to a grid or resize things without distorting them, you can’t measure pixels or vectors, or typeset text in any exact way. As someone with OCD, I often find myself in programs like Photoshop or Illustrator caught up in all the tiny details, always measuring something three times and making sure everything is lined up perfectly.â€Â

Reinhard further informed Observer, “The art I’ve made in the EZM has in many ways been free from this neurotic perfectionism. The EZM replaces the word “precision†with “play.†It enables me to tap into a fun, unrestricted sort of creativity. This kind of imprecision is how Lawhead blurs the line between “tool†and “toy,†and is a part of the magic of the EZM.â€Â

This playful, unrestricted, anti-perfectionist vibe is what Lawhead was going for in their creation, hearkening to the ’90s era of freeware, a time when software wasn’t focused on capitalist extraction or maximum productivity and the Silicon Valley tech-bro stereotype was a distant reality. Lawhead’s intention of making something outside of the tech norm mixed perfectly with the collaborative and anti-capitalist verve of zine culture. “There was a point in the ’90s era freeware, where you had small developers just making silly, goofy software, and distributing it themselves and it was kind of like a movement,†they explained. “It was kind of like zine culture, with people exchanging free software.â€Â

The zine I Hate Seattle by Neffer LeMort Neffer LeMort

“Software itself has been extremely gentrified, it’s not really about the little people, and making stuff just for the hell of it, the stereotype now is Silicon Valley, and exploiting software. So it’s really cool to see the convergence of the old software model and how well it fits with zine culture.â€

The Maker has also harnessed the collectivity inherent in zine culture, something that has been at the root of the sub-culture since the 1970s and ’80s. Perhaps we cannot currently distribute zines in the streets because of the pandemic, but we can certainly post them online, hashtag them so the right people will find them, and resist the gentrification of the culture via pop stars.

“Zine culture in itself is so collaborative and the organic nature of how this tool grew is super collaborative, like a lot of the features in there I wouldn’t have had if people didn’t ask for it,†Lawhead explained to Observer, exposing the summation that is intrinsic to current online zine cultures. “People are telling me how to build it, and I’m watching how they make zines, and building the maker around that.â€

A quick search on Twitter reveals people’s creations with the tool, creations they’re all too eager to share online. And Lawhead adds them to the Maker gallery, where they can be perused for free. The convergence of freeware and zine culture has resulted in a creative space that aims to be accessible, collective, anti-productivity and anti-genre.

The e-zine A Handful of Recurring Dreams made by Jeremey Oduber using the Electric Zine Maker Jeremy Oduber

Jeremy Oduber, the author of the aforementioned A Handful of Recurring Dreams zine, told Observer that EZM introduced him to the zine community and the creativity that exists outside the market.

Oduber has been a part of the collaborative culture that surrounds EZM: he designed a digital booklet template that made zines easier to read online as the original template generated separate images or a downloadable PDF. “Nathalie has been kind enough to help promote my little HTML5 reader, and people seem to have responded to it well,†he told Observer. “It feels nice to be able to play a small part in people’s Electric Zine Maker experience.â€

This collaborative and free aspect of EZM is something Lawhead is proud of and doesn’t plan on ever abandoning. “The zine maker is free and I always want it to be this way. There’s no weird licensing, it’s yours, take it, hack around in it. It’s open source too so you can literally do whatever you want with it,†Lawhead said. “People are sharing their art, and the beautiful things they make with it–software should and can be that way too. I’m trying to bring back the idea that software can be cute, fun and silly. Like zine-making, it can be just about casually creating and existing on the machine, instead of very polished and maximized productivity.â€

Thinking back, this was the casually anti-capitalist grounding experience I was looking for months ago, when I was trying to escape the pressure of hyper-productivity of surviving the pandemic and creating content that resonates with the historical moment. I found it briefly while folding sheets of paper on the floor and filling the pages with melodramatic yearnings for a better world. My mistake was taking myself too seriously, having rigid aims of making a zine every week when my mind was slipping away into the darkness of uncertainty. I still wanted it to make sense during a time where nothing made sense. What Lawhead and the Electric Zine Maker suggest is that seriousness is not always the best way to fight back against a system that doesn’t care about you; choosing lightness, lack of coherence, silliness and restful creation can be just as effective.

[ad_2]

Source link