[ad_1]

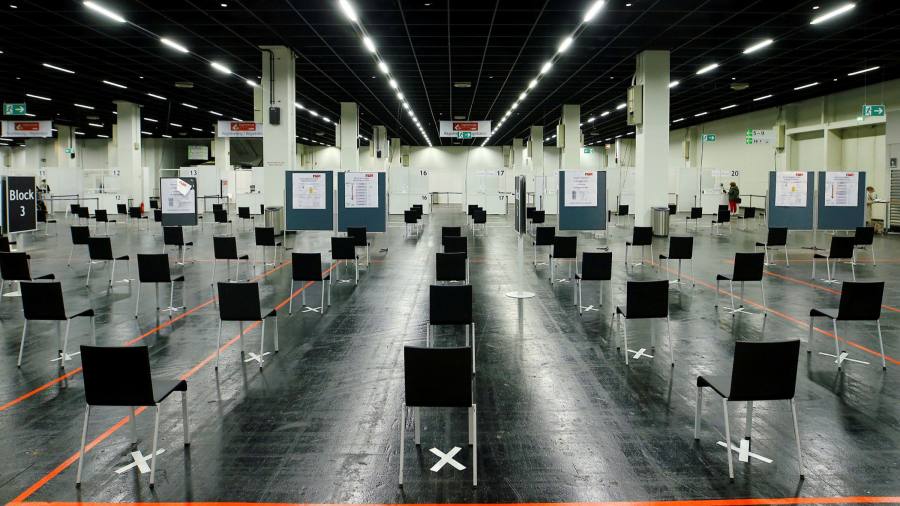

On Monday morning, a crowd turned up at the football stadium in Marseille, which has been largely shut to the public for a year. They were not hoping to see a match but to receive a long-awaited vaccine against Covid-19. The Velodrome had been inaugurated that morning as a mass vaccination centre.

By late afternoon, however, officials were turning people away after the French government, following safety fears over blood clots in Germany, halted use of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

The EU’s faltering vaccination campaign has been hamstrung by a botched central procurement process, supply shortfalls, logistical hurdles and excessive risk aversion from some national medical regulators. The suspension of the jab, albeit only for three days in most EU nations, was another hammer blow, with experts warning it would undermine public confidence and feed conspiracy theories about vaccine risks.

“If you had allowed the AstraZeneca vaccinations to continue, those 5-10 per cent of the population who are anti-vaxxers would have gone up the wall,†says Professor Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “But the position would have been clearer for the wider population.†She adds: “By having a message of doubt rather than a message of reassurance, that now plays into the hands of the anti-vaxxers. They are very well organised.â€

Just a few months ago, much of Europe was watching in bewilderment as the British and US governments mishandled the pandemic. The tables have rapidly turned. While the UK has now administered 40.5 vaccine doses per 100 people and the US 34.1, the EU has only managed 12.

Europe’s vaccination efforts were thrown into disarray this week at the worst possible moment. Many countries are in, or on the cusp of, a third wave of infections as the more transmissible B.1.1.7 variant — known in Europe as the “British mutation†— becomes dominant. Intensive care wards are filling up. Poland, Italy and swaths of France, including the Paris region, have gone back into lockdown while Germany’s plans for escaping confinement are likely to be reversed. The economic recovery is on hold while fears of another lost summer, crippling the more vulnerable tourist economies of southern Europe, are rising.Â

This week’s events — whipsawing government positions, competing messages from regulators, excessive caution by scientific advisers and renewed threats from Brussels over supplies — have created a picture of rattled leaders losing their nerve as the pandemic takes another turn for the worse.

Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission president, chose that very moment — when the AstraZeneca vaccine was still suspended across most of the EU and with up to 45 per cent of doses delivered stuck in cold storage — to turn up the heat on the UK and US by threatening to seize vaccine exports and productions facilities to ensure better supply for EU citizens. Her sabre-rattling divided EU capitals, as some warned in a private meeting of ambassadors that threats of vaccine protectionism could backfire on the bloc.Â

The week has been “hugely damaging†for the EU and has thrown up “strong contradictions†that the bloc “normally tries to navigate better than it’s doing nowâ€, says Rosa Balfour, director of the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

“It feels like everyone’s scrambling and hoarding, hiding and blaming,†she says. “It just seems that nobody’s really in control — and there’s not sufficient trust.â€

Berlin concern

The vaccine made by the Anglo-Swedish company — one of only four approved for use in the EU by the European Medicines Agency — is a vital part of Europe’s immunisation strategy. The bloc is expecting 460m doses in the first half of the year, 100m of them from AstraZeneca in a target revised substantially downward. But its vaccine has been the object of suspicion from the outset.Â

Its clinical trial data was incomplete. Several countries limited its use in older people, despite the EMA seal of approval. Anecdotal reports of side-effects fed scepticism. Emmanuel Macron, the French president, called it “quasi-ineffective†in the elderly, before recanting. Chancellor Angela Merkel admitted it had an “acceptance problem†in Germany. A bitter row between the European Commission and the company over its failure to meet agreed deliveries hardly helped.

Worries about the vaccine intensified earlier this month when Austria and Italy reported severe reactions and withdrew certain batches. Denmark and other member states followed suit as did Norway, despite the EMA insisting that the benefits of continued use outweighed the risks. Last weekend the French, Italian and German governments were still vouching for its safety. “We must have confidence in this vaccine and get vaccinated,†Jean Castex, French prime minister, said on Sunday.

However, the following day, the Paul Ehrlich Institute, Germany’s vaccines agency, informed ministers that six young to middle-aged women had suffered a particular type of severe haemorrhage in a vessel that drains blood from the brain. One patient in Munich was reported to have blood clots “from head to toeâ€.

The institute said the AstraZeneca jab should be withdrawn pending further analysis. Berlin changed position and halted its use, leaving its allies little choice but to follow suit — or face being seen as playing down the risks.

“If we swept it all under the rug, and reports of blood clots after vaccination started to leak out, then this would damage public trust even more than this temporary suspension might do,†says a French official.

Alerted to Berlin’s intention to suspend the jab, Italian prime minister Mario Draghi consulted with Merkel and then Macron. The three leaders and Pedro Sánchez, their Spanish counterpart, co-ordinated their announcement, creating the impression they were not acting on their own scientific assessment but at Germany’s behest — or to cover themselves if a problem with the vaccine was identified.

A French minister told Le Monde that Paris had been bounced into the suspension decision by Berlin, suggesting France’s move was not driven by science. “We had agreed to wait for the opinion from the EMA but Berlin moved first under internal pressure,†the minister said. “The worry was there, and the about-face in Germany meant we could not wait.â€

On Thursday, the European regulator, after reviewing laboratory and clinical evidence, said the vaccine was “safe and effectiveâ€. It could not find a causal link, but could not rule one out definitively either. France, Germany, Italy and Spain reversed course and said AstraZeneca jabs would soon resume but Norway, Sweden and Denmark maintained the suspension.

German health minister Jens Spahn said the EMA’s reassessment of the vaccine’s safety “confirmed our approach†and that it would have been “irresponsible†to keep jabbing it into people’s arms. But his political rivals and medical experts said even a short suspension will have cost far more lives — from delayed inoculations and lower vaccine take-up — than caused by a rare form of blood clotting.

Katrin Göring-Eckardt, leader of the Greens in the German parliament, says it was “unfathomable†how Spahn had reached his decision to suspend use of the vaccine. “It has led to confusion and uncertainty throughout the country,†she says.

Adds Karl Lauterbach, the Social Democratic party’s health expert: “The damage incurred by suspending vaccinations, even if only for a short time, is greater than the damage that would arise if this rare complication occurs.â€

Some see Germany’s knee-jerk response as a further example of Europe’s excessively cautious approach to vaccine science during the pandemic — like the national restrictions on the use of AstraZeneca for older people or the attempts to limit public liability for vaccine side-effects which delayed procurement deals.

“The precautionary principle is there to protect the decision makers,†says Christian Hervé, a professor of medical ethics at the Foch Hospital in Paris. “That’s where we are now.â€

“[The Paul Ehrlich Institute] went by what it says in the book rather than possibly considering the wider consequences, particularly for public confidence,†says Prof Kampmann. “They’ve been playing it by the book. But they used the wrong book in my opinion.â€

Kampmann faults Spahn for not over-ruling his vaccine regulators after weighing the very small chance of fatal blood clots against the much higher chance of dying from Covid-19 and the risk of undermining public confidence in the vaccine.

Christian Drosten, head of the Institute of Virology at Berlin’s Charité Hospital and one of the Germany government’s top advisers on coronavirus, also suggested it could have taken a different approach.

“As politicians, or as a ministry, we have to recognise that there is a pandemic and there are other values which one must set against that, for example the medical collateral damage that arises when people are not vaccinated just as a third wave is coming on,†he said in his weekly podcast.Â

Spahn is under huge pressure. Germany’s successful handling of the first wave of coronavirus last year made it the envy of Europe and revived the popularity of the governing Christian Democrats after 15 years in power. But Germany’s much criticised vaccine programme and the prospect of an extended lockdown as the country struggles to get the virus under control has become a political liability six months before parliamentary elections. A rout for the CDU in regional elections last Sunday has only raised the stakes.

Hardline intervention

Von der Leyen is another Christian Democrat who has come under heavy criticism. She has been excoriated in the German media for the commission’s vaccine procurement problems. Some were baffled she chose to talk tough on exports when she also had good news to announce: the EU is now expecting at least 360m vaccine doses from April to June — even with the scaled back deliveries from AstraZeneca.

That is more than four times as many as so far delivered and enough to enable the bloc to hit its target of inoculating 70 per cent of adults by September.

The commission president on Wednesday called for “reciprocity†on vaccines from countries such as the UK, which has received around 10m doses of EU-made vaccine in the past month and a half, while exporting none in return. She reiterated her message in a discussion with Boris Johnson, the UK prime minister, on Wednesday evening.Â

But Jacob Kirkegaard, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, says the timing of Von der Leyen’s hardline intervention on vaccine exports was “extremely oddâ€, because she had a positive message to deliver on supply. “It’s entirely driven by domestic politics.â€

Stella Kyriakides, the EU health commissioner, conveyed that more optimistic message in an interview with the FT and other media the same day, saying: “We are seeing a light at the end of the tunnel with the vaccinations — we are not where we were a few months ago.†As for criticisms that the EU had moved too slowly, she insisted “we never cut corners on safety and citizens know thisâ€.

EU governments will now try to get their vaccination programmes back on track, with a rapid acceleration expected this spring. Castex, the French premier, volunteered himself for an AstraZeneca injection on Friday. But it will take a lot more than that to restore confidence in a country where there is strong vaccine scepticism. A snap opinion poll for BFM TV on Tuesday found that only 20 per cent of respondents had confidence in the Anglo-Swedish vaccine.Â

France, like several other countries, initially limited the AstraZeneca vaccine to the under-65s. On Friday, it reauthorised its use but this time only for the over-55s — another dizzying change that could confuse the public.

Ben Hall in London, Michael Peel and Sam Fleming in Brussels, Leila Abboud in Paris and Guy Chazan in Berlin

[ad_2]

Source link