[ad_1]

This article is part of the The DC Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox every weekday.

About halfway through the second act of Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda reaches for George Washington’s farewell letter to script the Founding Father’s exit from the show’s plot. Theater kids—and their parents—no doubt have heard some of those words on a loop for years. But outside the original cast recording, there are other passages of Washington’s sign-off that were prescient, especially when it comes to outsiders’ efforts to meddle in American affairs. “Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government,” Washington wrote.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

In other words: foreign capitals are going to meddle. Hence, yesterday’s indictment of yet another Donald Trump pal was almost inevitable.

Through the centuries, the U.S. government has taken steps to guard against the sort of political interference from abroad that Washington warned about, although not always to great success. Nor has the U.S. followed its own edict—also found in Washington’s farewell—to stay neutral in foreign affairs and to avoid wading across borders with indifference for other nations’ sovereignty. Typically, at least, the State Department is left embarrassed when U.S. operations are caught trying to rig elections or assassinate leaders. It’s not exactly something Americans celebrate, that whole hypocrisy racket.

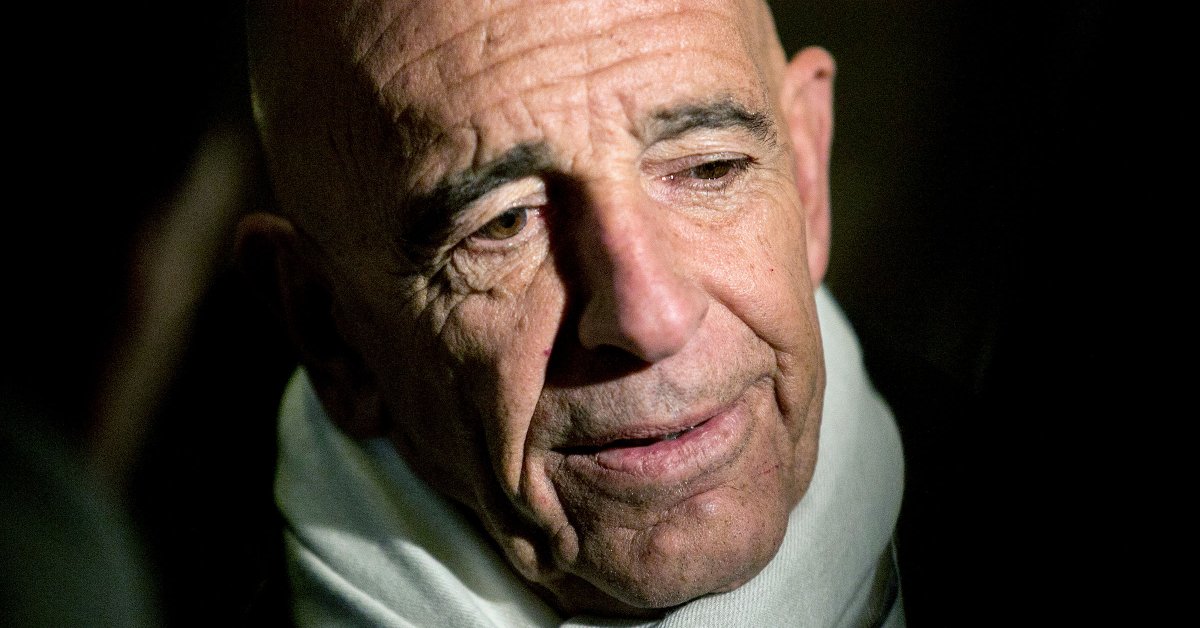

The Justice Department yesterday charged billionaire Thomas Barrack and two of his associates of failing to register as agents for a foreign government. (Barrack has denied any wrongdoing.) It’s not against the law for Americans to advocate for foreign governments; the most recent U.S. government database shows 485 American firms are registered with the Justice Department to work on behalf of foreign governments. They are, at their most benign, efforting to get on D.C.’s radar for this military base, that aid project or those must-have technologies. It’s not just Americans on K Street lobbying for U.S. dollars from U.S. lawmakers and policy wonks; outsiders to Washington often turn to some of Washington’s biggest power players to get them the meetings they otherwise wouldn’t be able to secure.

But failing to register as a foreign agent under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) is a big no-no. Generally speaking, you don’t get to rep foreign patrons’ interests to your pals in—or heading to—the White House without some disclosure.

Prosecutors say Barrack—perhaps Trump’s only true friend—used his connections with the President to push the political interests of the United Arab Emirates, and then obstructed justice and lied to investigators about it during a 2019 interview. They say Barrack asked UAE officials for a “wish list” in 2016 that the Trump Administration could deliver to the Gulf State. And, according to prosecutors, Barrack used his connection with Trump and his advisers to push that agenda—all while operating outside the registration system that discloses foreign agendas.

In return, investments from UAE and its close ally Saudi Arabia flowed to Colony Capital, as Barrack’s company was known at the time. From the time Trump became the Republican nominee until the Justice Department started its investigation into Barrack in 2019, Colony Capital collected $1.5 billion in investments from UAE and Saudi accounts, about one-third of which was directly from sovereign wealth funds controlled by the governments.

Foreign governments lobby Washington all the time. While some—ahem, Joe Biden—have gone for the cheap applause by proposing an outright ban on foreign lobbying, it’s generally a fine idea to not wall off America’s political system from the rest of the world. After all, the Constitution doesn’t create two classes of the First Amendment’s right to petition the government—aka lobby—between citizens and non-citizens. With the proper safeguards and transparency, it actually makes sense for foreign governments to work with private players to help navigate Washington. After all, who can expect a new ambassador to understand the quirks of the Byrd Rule when many members of Congress do not?

But it’s the shadiness of these systems that bolsters D.C.’s reputation as “The Swamp,” a cesspool of self-interest that Trump vowed to drain but ultimately flooded. It turns out the shores of the Potomac are tough to dry out, and have been for many decades. America’s first formal efforts at curbing foreign politicking in the United States came in 1917, when lawmakers considered early restrictions that probably weren’t entirely politically fair. The following year, a Senate panel found German and Bolshevik influence operations in the United States had donated to political campaigns, subsidized newspapers and magazines and bought off writers. With the rise of Nazism making Europe understand the threat, the U.S. House created a Special Committee on Un-American Activities in 1934, which, among other things, recommended a registration system for Americans working on behalf of foreign interests and limiting the time foreigners could stay in the United States if they were practicing propaganda. FDR signed into law the Foreign Agents Registration Act in 1938.

Now, 83 years later, the current iteration of that act is why one of Trump’s best friends is in jail. He’s not the first Trump ally to cross FARA. Last year, Trump mega-donor Elliott Broidy pleaded guilty to failing to register his work lobbying the Trump-era Justice Department on behalf of the Chinese and Malaysian governments. Former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort and his deputy Rick Gates both pleaded guilty to failing to register while lobbying for the government of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Party of Regions and former Ukrainian President Yanukovych. Trump’s first National Security Adviser Michael Flynn pleaded guilty to lying on his FARA registration forms to help Turkey.

With the exception of Gates, all of those influence peddlers were given a presidential pardon from Trump. But Trump’s pardon powers ended at noon on Jan. 20. He can no longer spare his allies scrutiny and perhaps punishment if prosecutors can make their case. It’s why the case against longtime Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg and now the indictment of Barrack are keeping the crowd at Trump’s private golf club in New Jersey nervous. If you’re noticing a pattern here of a tightening vise on Trump, you’re not alone. And it’s why Trump’s allies are wishing he could be humming one specific tune from Hamilton: “One Last Time.”

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the daily D.C. Brief newsletter.

[ad_2]

Source link