[ad_1]

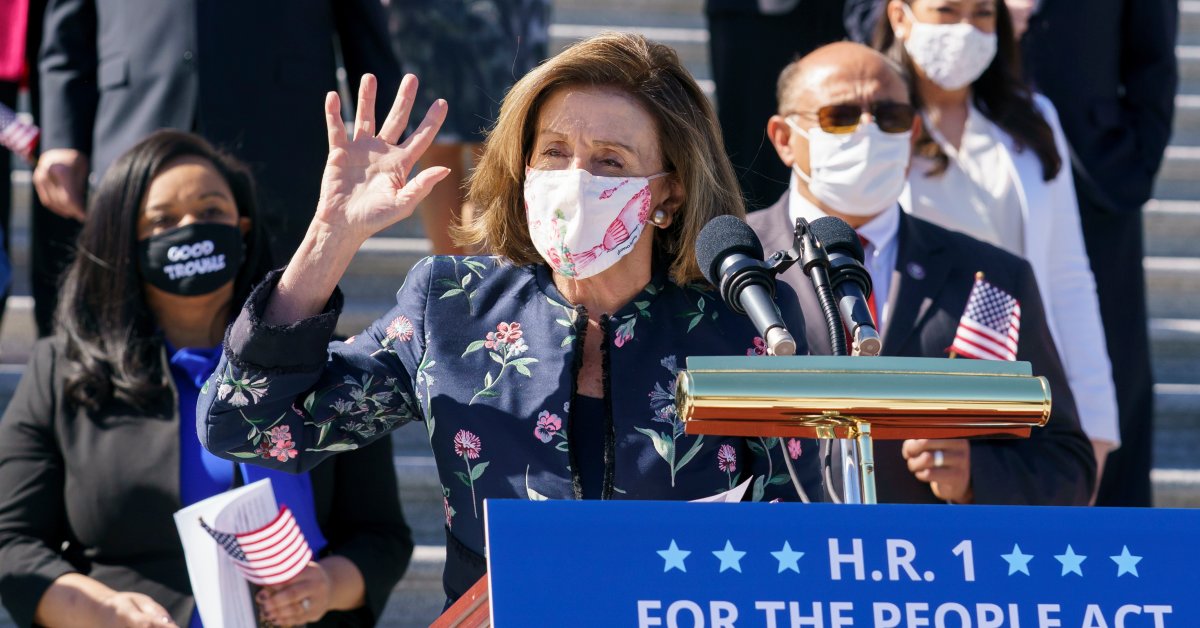

(WASHINGTON) — House Democrats passed sweeping voting and ethics legislation over unanimous Republican opposition, advancing to the Senate what would be the largest overhaul of the U.S. election law in at least a generation.

House Resolution 1, which touches on virtually every aspect of the electoral process, was approved Wednesday night on a near party-line 220-210 vote. It would restrict partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts, strike down hurdles to voting and bring transparency to a murky campaign finance system that allows wealthy donors to anonymously bankroll political causes.

The bill is a powerful counterweight to voting rights restrictions advancing in Republican-controlled statehouses across the country in the wake of Donald Trump’s repeated false claims of a stolen 2020 election. Yet it faces an uncertain fate in the Democratic-controlled Senate, where it has little chance of passing without changes to procedural rules that currently allow Republicans to block it.

The stakes in the outcome are monumental, cutting to the foundational idea that one person equals one vote, and carrying with it the potential to shape election outcomes for years to come. It also offers a test of how hard President Joe Biden and his party are willing to fight for their priorities, as well as those of their voters.

This bill “will put a stop at the voter suppression that we’re seeing debated right now,” said Rep. Nikema Williams, a new congresswoman who represents the Georgia district that deceased voting rights champion John Lewis held for years. “This bill is the ‘Good Trouble’ he fought for his entire life.”

In a statement, Biden said he looked forward to refining the measure and hoped to sign it into law, calling it “landmark legislation” that is much needed “to repair and strengthen our democracy.”

To Republicans, however, it would give license to unwanted federal interference in states’ authority to conduct their own elections — ultimately benefiting Democrats through higher turnout, most notably among minorities.

“Democrats want to use their razor-thin majority not to pass bills to earn voters’ trust, but to ensure they don’t lose more seats in the next election,” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy said from the House floor Tuesday.

The measure has been a priority for Democrats since they won their House majority in 2018. But it has taken on added urgency in the wake of Trump’s false claims, which incited the deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol in January.

Courts and even Trump’s last attorney general, William Barr, found his claims about the election to be without merit. But, spurred on by those lies, state lawmakers across the U.S. have filed more than 200 bills in 43 states that would limit ballot access, according to a tally kept by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University.

In Iowa, the legislature voted to cut absentee and in-person early voting, while preventing local elections officials from setting up additional locations to make early voting easier. In Georgia, the House on Monday voted for legislation requiring identification to vote by mail that would also allow counties to cancel early in-person voting on Sundays, when many Black voters cast ballots after church.

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court appeared ready to uphold voting restrictions in Arizona, which could make it harder to challenge state election laws in the future.

When asked why proponents sought to uphold the Arizona laws, which limit who can turn in absentee ballots and enable ballots to be thrown out if they are cast in the wrong precinct, a lawyer for the state’s Republican Party was stunningly clear.

“Because it puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats,” said attorney Michael Carvin. “Politics is a zero-sum game.”

Battle lines are quickly being drawn by outside groups who plan to spend millions of dollars on advertising and outreach campaigns.

Republicans “are not even being coy about it. They are saying the ‘quiet parts’ out loud,” said Tiffany Muller, the president of End Citizens United, a left-leaning group that aims to curtail the influence of corporate money in politics. Her organization has launched a $10 million effort supporting the bill. “For them, this isn’t about protecting our democracy or protecting our elections. This is about pure partisan political gain.”

Conservatives, meanwhile, are mobilizing a $5 million pressure campaign, urging moderate Senate Democrats to oppose rule changes needed to pass the measure.

“H.R. 1 is not about making elections better,” said Ken Cuccinelli, a former Trump administration Homeland Security official who is leading the effort. “It’s about the opposite. It’s intended to dirty up elections.”

So what’s actually in the bill?

H.R. 1 would require states to automatically register eligible voters, as well as offer same-day registration. It would limit states’ ability to purge registered voters from their rolls and restore former felons’ voting rights. Among dozens of other provisions, it would also require states to offer 15 days of early voting and allow no-excuse absentee balloting.

On the cusp of a once-in-a-decade redrawing of congressional district boundaries, typically a fiercely partisan affair, the bill would mandate that nonpartisan commissions handle the process instead of state legislatures.

Many Republican opponents in Congress have focused on narrower aspects, like the creation of a public financing system for congressional campaigns that would be funded through fines and settlement proceeds raised from corporate bad actors.

They’ve also attacked an effort to revamp the federal government’s toothless elections cop. That agency, the Federal Election Commission, has been gripped by partisan deadlock for years, allowing campaign finance law violators to go mostly unchecked.

Another section that’s been a focus of Republican ire would force the disclosure of donors to “dark money” political groups, which are a magnet for wealthy interests looking to influence the political process while remaining anonymous.

Still, the biggest obstacles lie ahead in the Senate, which is split 50-50 between Republicans and Democrats.

On some legislation, it takes only 51 votes to pass, with Vice President Kamala Harris as the tiebreaker. On a deeply divisive bill like this one, they would need 60 votes under the Senate’s rules to overcome a Republican filibuster — a tally they are unlikely to reach.

Some Democrats have discussed options like lowering the threshold to break a filibuster, or creating a workaround that would allow priority legislation, including a separate John Lewis Voting Rights bill, to be exempt. Biden has been cool to filibuster reforms and Democratic congressional aides say the conversations are fluid but underway.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has not committed to a time frame but vowed “to figure out the best way to get big, bold action on a whole lot of fronts.”

He said: “We’re not going to be the legislative graveyard. … People are going to be forced to vote on them, yes or no, on a whole lot of very important and serious issues.”

___

AP Congressional Correspondent Lisa Mascaro contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link