[ad_1]

Safwan Thabet has long enjoyed a reputation as one of Egypt’s most successful businessmen, nurturing his small family company into the country’s pre-eminent dairy producer despite the Arab state being rocked by social and political unrest over the past decade.

But now a huge cloud of uncertainty hangs over Juhayna Food Industries as the 75-year-old who founded and chaired the group languishes in Cairo’s notorious Tora prison after being arrested in December over accusations of financing and being a member of a terrorist organisation.

The Cairo-listed company, which counts global fund managers among its investors, hoped Seif el-Din Thabet, Safwan’s son and the chief executive, would steady the ship. But in February, the acting chair was detained and charged with the same offences, leaving the group’s leadership in limbo.

The company’s directors have since had to explain to banks, investors and clients what is going on in the business, which is 51 per cent owned by the Thabet family, while Juhayna’s 4,000 employees fret about the future.Â

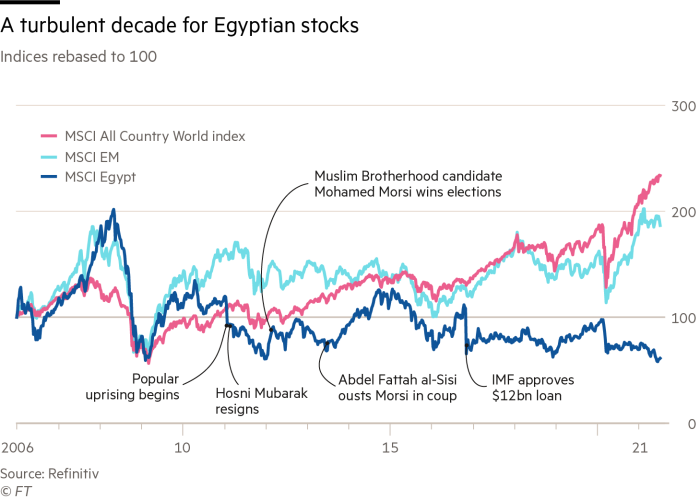

For analysts, the saga epitomises the unpredictability that the private sector faces in Egypt, where President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s regime has used the accusation of terrorism to target activists, academics, journalists and business people since ousting the Muslim Brotherhood in a 2013 coup.

At the same time, Sisi, a former army chief, has expanded the military’s footprint across the economy, cowing the private sector as companies find themselves having to contend with the state’s most powerful institution.

Victims of a crackdown?

“For portfolio investors, it suggests uncertainty across the board. Juhayna is a terrific stock, everyone likes the stock. It’s a well-run company, a consumer play in a market of 100m people — it’s got everything going for it, then something like this happens,†said François Conradie, lead political economist at NKC African Economics, a research firm that is part of Oxford Economics.

“It casts doubts on the attractiveness of the Egyptian stock market — never mind going to Egypt as a greenfield investor and trying to set something up.â€

Friends of the Thabet family believe the father and son are victims of a crackdown that initially targeted members and supporters of the Islamist movement — which briefly took power at elections after the popular uprising in 2011 — but has since morphed into a broad campaign against all forms of criticism or dissent.

They acknowledge that Safwan Thabet’s father and grandfather were senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood, but insist that the businessman “has zero ties†to the group and “zero interests in any political activityâ€. The Thabets have yet to be tried. The Egyptian government did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Theoretically, the company can survive’

Two friends of the family told the Financial Times that days before Seif was arrested security agents warned him that he faced his father’s fate unless he “signed over the whole companyâ€. Seif replied that he was not at liberty to sign on behalf of the family or other investors and 48 hours later he was behind bars, they said.

They believe that “negotiations†are taking place between the security agencies and the detained Thabets — the implication being that the state is seeking to expropriate the business in return for their release.

“Theoretically, the company can survive. But if the government decides this company shouldn’t operate, they have all the tools to stop it,†said a family friend, speaking from outside the country. “There must be some sort of compromise or deal. What sort of a deal it is, is up to the guys inside.â€

After Sisi seized power, his government designated the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organisation and confiscated the assets of hundreds of companies that were allegedly linked to the movement. Non-governmental organisations, hospitals and schools associated with the group were also shut down. Tens of thousands of supporters and members of the brotherhood have been jailed.

‘If you are driving a Juhayna car, you will be put in prison’

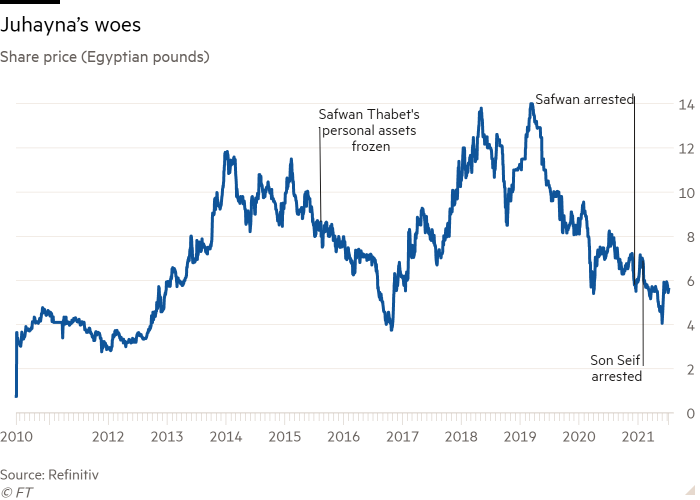

Safwan Thabet’s troubles began in 2015, when his personal assets were frozen because of his alleged links to the Brotherhood. But he continued as Juhayna’s chair.

Three months earlier, he had sealed a joint venture with Arla Foods, Scandinavia’s biggest dairy producer, and around the time his assets were frozen, Aberdeen Asset Management, one of the UK’s largest fund managers, increased its holding in the company to 5 per cent.

Seif took over as chief executive in 2016 and was appointed deputy chair. Both Thabets were on the boards of business associations, including the Federation of Egyptian Industries and the Chamber of Food Industries.

Despite the asset freeze more than five years earlier, Safwan’s arrest still shocked those close to him. “It doesn’t make any sense that the government and intelligence would have someone who’s allegedly leading and financing a terrorist group and you just leave him for the past six years to do business, meet the president, meet high-level officials [and] invest in the country,†a family friend said.

After his detention, police stopped Juhayna’s trucks, withdrew vehicle licences and threatened drivers by telling them, “if you are driving a Juhayna car, you will be put in prison,†people close to the Thabets said.

‘These people don’t want to relinquish control’

Juhayna’s market capitalisation, which reached E£13bn ($828m) in 2019, has since plummeted to $330m — a 60 per cent fall. The Egyptian stock market, which has underperformed against its emerging market peers, has lost about 30 per cent of its value over the same period.

Some foreign investors have sold down their stock. Aberdeen Standard Investments, as it has since been renamed following a merger with Standard Life, no longer holds Juhayna, while Arla Foods said it decided last year to “downscale our collaboration†with the Egyptian company “due to difficult market conditionsâ€. However, the Norwegian oil fund still owned 4 per cent at the end of last year.

An international fund manager said Egypt was a “market with significant growth opportunities and exceptionally well-managed companiesâ€. But they added that it was “one where governance concerns have risen materially in recent years and where dwindling liquidity in the stock exchange has made investing a materially riskier prospectâ€.

Another banker said there were lots of hope in Egypt after the government pushed through painful economic reforms in 2016 to secure a $12bn IMF loan. But now, “there’s a lot of disappointment from investorsâ€.

“At the end of the day, these people [the regime] don’t want to relinquish control, so they aren’t comfortable with creating conditions where the private sector can thrive,†he added.

[ad_2]

Source link