[ad_1]

Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky, 93, is calmly screening a copy of the 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides’s meditations on marriage. Beside him, yelling into his nearly deaf ear, is his grandson. The question being transmitted via a call from New York to Bnei Brak, a Tel Aviv suburb that is home to some 200,000 deeply devout ultra-Orthodox Jews: can a follower of the rabbi marry a woman whose name sounds almost like his mother’s?

The rabbi assents. The Torah, a religious text, is clear on this issue; vague on others. For hundreds of thousands of fervently devout Jews, Kanievsky is the posek, the decider of God’s law, the spiritual heir to a long line of rabbis.

But in all his life, almost cut short by the coronavirus itself last year, Kanievsky has faced no dilemma as profound as the one he does now. What should the Haredi, ‘those who tremble before God’ in Hebrew, do in the age of Covid-19? For the devoutly religious community, self-segregated from modern Israel, there is no simple answer.

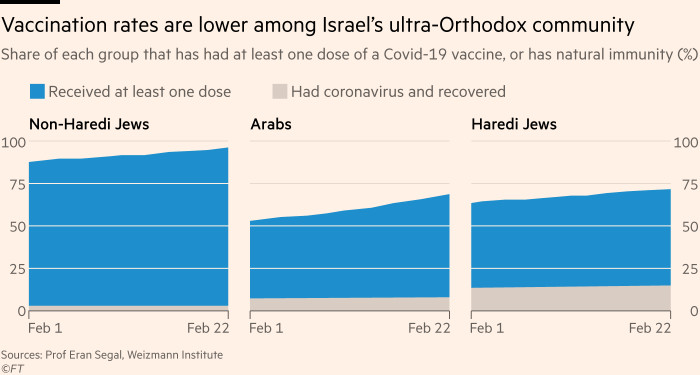

Even as its much-lauded vaccination programme means the pandemic in Israel appears to be easing, the scale of deaths in the Haredi community has brought it to a moment of crisis. While their outsize political clout may have allowed them to ignore coronavirus restrictions — prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu counts on their support — they are beset by the disease, reviled by secular Israelis and diminished by radical, anti-Zionist rabble-rousers within their own community. Even now, many Haredi are reluctant to take a vaccine from a state they distrust.

Since before the birth of the state in 1948, the Haredi have fought to maintain their way of life, the rituals of birth, worship and study preserved in a simulacrum of 1850s eastern Europe. Many only reluctantly accept the authority of the state, which they see as the creation of secular Jews, not God.

With the outbreak of the pandemic, Israel, like the rest of the world, instituted a tough lockdown. But for the Haredi, shuttering yeshivas and synagogues would shatter their routine of uninterrupted prayer and be tantamount to blasphemy, heralding the end of the universe. “Heaven forbid,†exclaimed Kanievsky, when asked last year if religious schools should be closed on orders from the government.

Others have suggested a more practical explanation: closing them would unmoor young Haredi men from the discipline of prayer, leaving them open to the temptations of the modern world, said Yehoshua Pfeffer, a prominent rabbi.

Soon, the very customs that set the Haredi apart from their fellow Israelis — collective prayer, packed seminaries, the touching and kissing of rabbis and fading Torah scrolls — became a cradle for the virus.

During last year’s first wave, seven in 10 Israeli hospital beds were taken by ill Haredi, even though they number a little more than a tenth of the population. A year later, one in 100 of their elderly are dead. If all of Israel had suffered as they had, its national death toll of nearly 5,800 people would have been four times higher.

‘They thought a blessing would be enough’

“What is going [on] right now is pure chaos — this is the worst it has been since the state of Israel was born,†said Yehuda Meshi-Zahav, a rabbi who runs an aid organisation that collects the dead for burial, and has spent months warning the Haredi about coronavirus.

“In the beginning, no one understood,†said the 61-year-old. “They thought a blessing would be enough.†His warnings went unheeded, even within his own family, and finally, death came to Meshi-Zahav’s home, “staring me in the eyeâ€. First, his brother — his best friend — died. Then his mother. Days later, his father, a renowned scholar of the Torah.

At the funerals, no one spoke of the coronavirus, he said. By then Meshi-Zahav was a pariah for speaking out. His organisation’s ambulances were stoned by Haredi protesters when they drove through strictly segregated towns to pick up the dead. For his troubles, he was awarded the nation’s most prestigious honour, the Israel Prize, on Tuesday.

“I told them — look, I couldn’t save my parents. They didn’t respect the rules, and they died,†he said. “Only when everybody has paid a personal price, the community will have to understand that they will have to change but, in the meantime, history will judge the leadership.â€

The Haredi’s leaders were slow to act. Thanks to David Ben-Gurion, the nation’s founder, Haredi men study in yeshivas for years rather than serve in the military. Kanievsky closed them only after a national outcry and kept them open in later lockdowns, albeit with some restrictions. They won permission to lock yeshiva students in, something denied to secular universities. While prominent rabbis eventually ordered people to observe coronavirus restrictions, many did not listen.

The ideas that worked for the rest of Israel were more difficult to implement in Haredi households. Home isolation turned crowded apartments into hotbeds of infection. The army, reviled in the community as an agent of secularisation, came into Haredi neighbourhoods handing out food and taking the sick to hospital.

The sight of the army on their streets was interpreted as a failure of establishment rabbis such as Kanievsky. Staunchly anti-Zionist radicals surged into the clerical vacuum, fighting the police on the streets, flouting lockdowns and becoming the public face of an already misunderstood community.

‘We haven’t taken one shekel from them’

With his black suit, plain white shirt, long curly hair and large kippah, the Rabbi Youlish Krois looks much like Rabbi Kanievsky’s followers. But Krois belongs to the Neturai Karta — the Guardians of the Gate — a radical group that despises the Zionist state. Most pay no taxes and take nothing from the state.

His is the most extreme of anti-Zionist groups, sending representatives to Iran and the Gaza Strip to help bring the end of Israel — but anti-Zionist Haredi number at least 100,000, most falling under a group called the Eda Haredit.

When the virus came, the Eda Haredit stocked up on medicines and used donations to buy 400 ventilators. None of Krois’s people, he said, went to a Zionist hospital, and none, he vows, will take the vaccine.

“Those who take money from the state, you can say, to them, ‘You need to respect the rules,’†he said, sitting in the courtyard of his three-bedroom home, where his 18 children sleep in cupboards and on the floor. “We haven’t taken one shekel from them, and still they come and close our schools?â€

‘It hurts the rabbi that people think the Haredi are like this’

Fundamentalists such as Krois have fuelled a national obsession with Haredi behaviour that makes little effort to differentiate between the openly defiant and those struggling with the virus, such as Rabbi Kanievsky.

Israelis blame the Haredi for the explosion of the virus, even as they flouted restrictions themselves — crowding beaches, going to weekly anti-government protests and houses parties.

“Fuck these parasites,†yelled a bleeding policeman, during a January protest in Jerusalem’s Mea Shearim neighbourhood where he was spat on, called a Nazi, and finally, attacked with a metal rubbish bin for trying to shut down a small funeral.

That word, parasite, with all its anti-Semitic undertones, is used by many Israelis to describe the Haredi, for choosing a life of religious study over work and military service, and bearing little of the burden of the taxes and employment that support the state. They are regularly mocked for their distinct modest clothing, segregation of the sexes and shunning of the modern world — two weeks ago, a primetime comedy show lampooned Kanievsky and his grandson, and their relationship with Netanyahu.

“What hurts the rabbi [Kanievsky] is the innocent people who see the evening news, they see a Haredi burning a bus, beating the police — it hurts the rabbi that people sit and think the Haredis are like this,†said Yaakov Kanievsky, his grandson, who speaks on behalf of the rabbi.

“The rabbi never said there is no corona — he said, ‘I want the government to find a solution for the yeshivas, just like they did for the military’,†said Yaakov, referring to the decision to allow soldiers to remain on base. Unlike other rabbis, Kanievsky has told his followers to get vaccinated, sending his grandson to be among the first in the Haredi community to receive his jabs in front of the media.

With elections in late March, Netanyahu’s long-running alliance with the Haredi has become a political liability for him — two of his rivals are running on a platform of denying the community a chance in a coalition.

“The media sees us as a tool in the game of politics, because we are seen as identified with the prime minister,†said Yaakov. “We are the hostages — under attack as if we are responsible for the spreading the virus all over the country.â€

Meshi-Zahav, the rabbi medic who has watched with dismay as Haredi society floundered in the face of the virus, warns that worse is to come. “The Haredi don’t understand how much they are hated by the secular,†he said. “In times of crisis, Jews used to band together. From now on, it will be different.â€

[ad_2]

Source link