[ad_1]

Jack Ma’s Ant Group has undercut, undermined and insulted China’s big state-owned banks for years. Regulators have now turned the tables on the financial technology group after forcing the company to pull its record $37bn initial public offering in November.

Beijing is targeting the symbiotic relationship that has transformed China’s financial system by matching loans from small regional banks with 500m borrowers via Ant’s Alipay app, the country’s biggest payments platform.

Under new rules that will be enforced from next January, Ant will be required to limit its business with regional lenders in favour of the big state-owned banks Ma derided as having a “pawnshop†mentality in a speech last October. The billionaire entrepreneur has largely vanished from public view since he made the comments in a dispute that has underlined growing tensions between the state and the private sector in China as President Xi Jinping tightens his grip on the economy.

The move to clip Ant’s wings came after the size and scale of the company’s lending operation, which was revealed in its IPO pitch, caught regulators off guard, according to several people familiar with the situation.

“The regulators were surprised that Ant would have a larger market capitalisation than China’s largest state-owned banks,†said one Chinese banker who advises the government on financial policy issues. “When the IPO was priced they looked at it and said: ‘What, this thing is bigger than JPMorgan?’â€

Rules designed to slow down Ant

Ant was responsible for arranging about one-tenth of China’s consumer lending last year via two products: Huabei, which is similar to a credit card; and Jiebei, which offers small unsecured loans through Alipay. Ant’s total outstanding loans reached Rmb2.2tn ($340bn) as of June 30.

About 90 per cent of the lending was underwritten by a network of 100 partner banks, many of which were smaller, regional lenders that offered competitive rates in exchange for access to Ant’s vast customer base and national reach.

The new rules mandate that joint-lending made through the internet can account for no more than half of any bank’s total loan book and lending through any single fintech platform cannot exceed 25 per cent of a bank’s tier one, or core, capital.

This will inevitably lead Ant to have to work more closely with the country’s bigger banks to expand its lending business, as China’s top 10 banks hold 64 per cent of the country’s total Rmb20tn of tier one capital, according to Bernstein.

“Since each player, especially the smaller ones, can do less, Ant has to do more with the bigger banks with big balance sheets,†said Kevin Kwek, an analyst at Bernstein. “This will weaken Ant’s bargaining position with them.â€

Bernstein has cut its estimate of Ant’s value from $310bn at the putative IPO price to $230bn and said it could fall further. “The model is not completely broken, but growth will be curtailed quite a bit,†said Kwek.

The rules also introduced regional restrictions, so a city bank in Beijing would no longer be able to extend Alipay loans to consumers in Shanghai.

“Ant has more than 100 financial partners but China only has roughly 20 national banks . . . the new rules on cross-region lending will hurt Ant a lot,†said Xiaoxi Zhang, a financial analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics, a research firm.

The Bank of Tianjin, for example, increased its consumer loan book by nearly 800 per cent in 2018 after it signed deals with Ant and other fintech platforms.

The Bank of Shizuishan, in China’s north-west Ningxia region, extended Rmb20bn in loans through Alipay over about 18 months to October, according to state media.

One lender in Hangzhou said Alipay lending had been so good for business that the company tiptoed around negotiations with Ant for fear the group would walk away.

To help fund their lending spree, analysts said, regional banks had offered attractive rates for deposit products on platforms such as Alipay. On January 15, regulators barred banks from offering deposit accounts on third-party online platforms.

“That basically cut their aggressive funding channel possibly used to fund the co-lending with fintech platforms,†said Jacky Zuo, an analyst with China Renaissance, an investment bank. “The trend is smaller banks are retreating from this type of co-operation.â€

Data sharing and risk management

The rules will force banks to complete credit assessments on potential borrowers themselves, rather than relying on Ant.

But most banks have mainly dealt in mortgages and business loans, situations in which borrowers have collateral, said Chen Long, a Beijing-based partner at Plenum, a consultancy.

“Banks don’t have the expertise, they don’t have the data†to assess consumer loan risk, he added. “The banks will have to find another way around this regulation.â€

Ant shares some borrower data with lenders but it may have to hand over much more to maintain its partnerships, although this may not suffice.

“Even if Ant hands over the data, small banks won’t even know what to do with all this data. They aren’t in a position to create sophisticated risk-management systems powered by AI algorithms,†said Linghao Bao of Trivium China, a research firm.

Taking on more credit risk

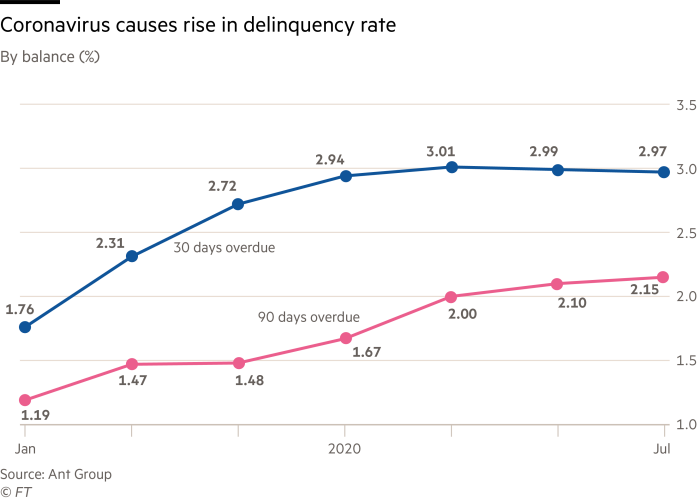

Chinese regulators were particularly perturbed that Ant earned fees on the loans it pushed to users without having to take on the credit risk.Â

The new rules decree that online lenders will have to self-fund 30 per cent of each loan they make with banks. It is unclear what portion of Ant’s lending business this will affect.Â

But an expansive application of the rule would turn Ant from an asset-light tech company into a capital-heavy business more akin to a bank. Bernstein noted a shift to on-balance sheet lending would actually improve Ant’s profitability, as the company would earn the interest income, but would also lower its return on capital.Â

“Not being an asset-light model will mean investors will punish the stock via weaker multiples,†it said.

Even though Ant reached a restructuring deal with Chinese regulators, the reorganisation of its business as a financial holding company will bring it directly under the thumb of the central bank.

The People’s Bank of China in January also took the unusual step of issuing draft rules that would allow it to push for the break-up of payments companies such as Ant on antitrust grounds.

Ant declined to comment.

Additional reporting by Nian Liu, Sun Yu and Tom Mitchell

[ad_2]

Source link