Four years ago, Don Sabbe made what he calls a “devastating” mistake. Determined only to cast a vote for a candidate he believed in, he left the top of his ballot blank in the 2016 presidential election. This year, the 83-year old former Chrysler employee says he’ll definitely vote for Joe Biden, but he’s getting concerned about Biden’s campaign here in Michigan.

“I can’t even find a sign,” Sabbe says outside a Kroger’s in Sterling Heights, where surrounding cars fly massive Donald Trump flags that say “No More Bullsh-t” and fellow shoppers wear Trump T-shirts for their weekend grocery runs. “I’m looking for one of those storefronts. I’m looking for a campaign office for Biden. And I’m not finding one.”

The reason Sabbe can’t find a dedicated Biden campaign field office is because there aren’t any around here. Not in Macomb County, the swing region where Sabbe lives. It’s not even clear Biden has opened any new dedicated field offices in the state; because of the pandemic, they’ve moved their field organizing effort online. The Biden campaign in Michigan refused to confirm the location of any physical field offices despite repeated requests; they say they have “supply centers” for handing out signs, but would not confirm those locations. The campaign also declined to say how many of their Michigan staff were physically located here. Biden’s field operation in this all-important state is being run through the Michigan Democratic Party’s One Campaign, which is also not doing physical canvassing or events at the moment. When I ask Biden campaign staffers and Democratic Party officials how many people they have on the ground in Michigan, one reply stuck out: “What do you mean by ‘on the ground?’”

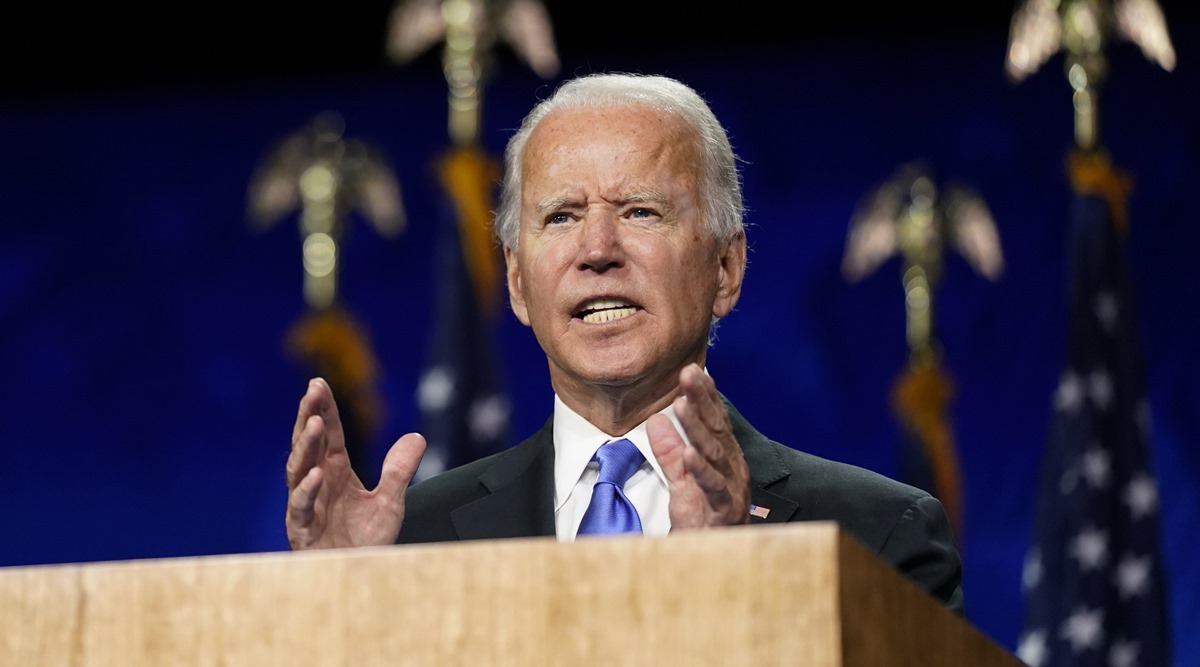

All this means there are no young volunteers in Biden shirts pounding the pavement for their candidate, no clusters of posters marking the Biden field offices in various precincts, few bumper stickers on the highways. There are more Biden signs than Hillary Clinton had in 2016, locals say, but not enough to give the impression of an enthusiastic presidential campaign in a crucial swing state. When Biden visited Michigan last week, only a handful of supporters came to see him; his campaign didn’t disclose the location of the event in advance, even to the local Democratic county chair, because it didn’t want to attract a crowd that could spread COVID-19 or violate Michigan’s prohibition on gatherings of more than 100 people.

In short, in one of the most important swing states in the country, Biden’s campaign is all but invisible to the naked eye. His lack of a physical footprint is all the more striking because Trump flags festoon everything from pickup trucks to massive airplane parts being transported down the highway. Roughly 30 Trump supporters gathered to protest outside the Biden event last week, waving their flags and cheering as passing cars honked. (Roughly eight Biden supporters showed up.) After driving around some of the state’s swing districts for the past week, talking to than dozens of voters, the only reason you’d think Biden was up in Michigan is because the polls have consistently said so.

Trying to evaluate the strength of the Biden campaign in Michigan is like trying to determine whether the Emperor has no clothes or is actually wearing an elaborate invisible suit. The Biden campaign says it’s swarming the state; you just can’t see it.

Biden’s Michigan team says its campaign is significantly bigger than Clinton’s and may be the largest program in the state’s history. The campaign says it reached out to 1.4 million voters during the Democratic convention and the weekend that followed, with 500 digital-organizing events and 10,000 volunteer signups. In the week before Labor Day, the campaign sent 500,000 texts to Michigan voters—one every half-second. It has just replaced the trappings of a traditional ground game—volunteers knocking on doors, distributing literature, and so forth—with a digital field operation.

This strategy makes sense during a global pandemic. The campaign is prioritizing public health at a moment when Trump is flagrantly disregarding it. But the juxtaposition of Trump’s loud and proud campaign and Biden’s invisible digital operation makes some Democrats increasingly anxious. “We don’t see the presence,” says Lori Goldman, the founder of Fems for Dems, a grassroots political action group with nearly 9,000 members in Michigan. “They should have people who are like Jehova’s Witnesses, zealots, preaching the gospel of Joe Biden out there in the community. There needs to be someone out there Biden-izing. People don’t even know where to volunteer for Biden.” Goldman says she gets roughly 15 calls a week from women asking where they can canvass, and she doesn’t know what to tell them. “Meanwhile,” she says, “there are Trump signs that look like they should be on an expressway, they’re so big.”

Democratic officials in Michigan and the Biden campaign say they’re confident that Biden will carry the state, where he has maintained a consistent lead by nearly every metric. “The difference between now and four years ago is immeasurable, and I’m very optimistic,” says Ed Bruley, chair of the Macomb County Democrats, who says he sees a steady stream of supporters coming by to pick up yard signs.

But after conversations with more than a dozen Democratic Members of Congress, state representatives, local party chairs and party operatives, a slightly more anxious picture emerged. Top Democrats believe the race is closer than the polls suggest, and some are privately urging the Biden campaign and state Democrats to reconsider physical canvassing. “I think Biden could absolutely do more,” says Michael Heitman, chair of the Democratic Party in Isabella County, a small county in central Michigan which voted for Barack Obama twice and then for Trump in 2016. “I’d really appreciate if the Biden campaign had someone specifically for his campaign here.”

Some top Democrats say that the visibility of Biden campaigning in Michigan is as important as the campaign itself. “I think we need a more visible Biden campaign presence in the state, that is soup to nuts: from yard signs to surrogates to visits,” says U.S. Congresswoman Elissa Slotkin, who represents Michigan’s 8th District. “I would love to see a steady drumbeat that made clear, even to the most apolitical person, that Joe Biden cares about Michigan, and he has plan.”

Granted anonymity to share candid assessments of the campaign, other top Democrats are more pointed. “Calling a telephone number isn’t a connection,” says one leading Michigan Democratic official. “Some of the same people that said everything was okay four years ago are the same people saying everything’s okay now.”

Since Clinton’s loss, Michigan Democrats have been terrified of repeating the mistakes that cost her the state by just over 10,000 votes and helped tip the election to Trump. And compared to Clinton, who took Michigan for granted and skimped on resources in the state, Biden is certainly doing a lot right. The Vice President visited last week to give a major speech about manufacturing and meet with union workers, while Dr. Jill Biden visited the state on Tuesday. Michigan officials, from members of Congress down to state representatives, say they have an open line of communication with the campaign, unlike in 2016.

Democrats in Michigan have been organizing nonstop since 2017 without pausing in between election cycles, thanks to the One Campaign’s unified field effort. In 2018 they flipped two House seats, kept a Senate seat, and elected a Democratic governor. Last year they knocked on more than 85,000 doors. In the August state primary, Democratic turnout was at a record high. “The success has been beyond my wildest dreams here,” says U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, who spearheaded the One Campaign.

Then came Covid-19. Early in the pandemic, the Biden campaign and the One Campaign decided that mounting a traditional field operation, with canvassers knocking on doors, was not worth the public health risk. Instead, they’re running a “digital field” operation, recruiting volunteers to make phone calls and send text messages for Democrats.

“There is nothing better than that face-to-face contact,” says Lavora Barnes, chair of the Michigan Democratic Party. “But nobody I know of has ever tried to campaign in the middle of a global pandemic. Contact with people, if not done correctly, is dangerous.”

On a national call with reporters on Sept 4, campaign manager Jen O’Malley Dillon said the Biden campaign had invested $100 million in “on-the-ground” organizing nationwide, but did not plan to focus on door-knocking. O’Malley Dillon is a veteran organizer who was Obama’s battleground states director in 2008. She calls this a “new organizing model,” and says the campaign had 2.6 million conversations with voters in battleground states in August.

“What matters about organizing is engaging with voters and having real conversations,” O’Malley Dillon said in a Politico forum on Tuesday. “We spent so much time talking about tactics, but fundamentally, knocking on a door and not reaching anyone doesn’t get you much except leaving a piece of lit behind.”

Still, Democrats are used to measuring their strength by their ground game, and without physical boots on the ground, the effect can be unsettling. It brings up uncomfortable questions about whether a “digital field” operation can really replace a “traditional field” operation without something being lost. Sure, it sounds like digital field organizing should work. But does it actually? Nobody knows, because it’s never been tried on this scale before.

Goldman of Fems for Dems says she’s ready to dispatch her army of women to knock on doors for Biden, if only the campaign would ask. The Biden campaign calls her for help finding Republican women who might be inclined to vote for Biden (“you might as well ask me to find you a unicorn,” she says), but not for help recruiting volunteers to knock doors. “I want them to ask me, ‘Give us a hundred women’s names and let us send them out like soldiers into the neighborhoods.’” She’s worried that focusing entirely on phone calls and emails means ignoring voters who may not show up in the data. “If you’re not in the system,” she says, “Joe Biden doesn’t even know how to reach you.”

Besides, she adds, Michigan is opening up. “If you’re allowed to go to Michaels, or you’re allowed to go to Target, I don’t see why they can’t go to a campaign office,” Goldman continues. Her voice starts to shake as she adds: “I’m afraid we’re losing. I’m afraid we’re going to lose.”

Even though Biden isn’t knocking on doors in Michigan, other Democratic candidates are. Goldman’s army of women is canvassing to flip the Michigan statehouse and elect Democrats to school boards and county commissions. Slotkin has been working doors in a socially distanced way, dropping off literature in her tight swing district in what she calls a “contactless canvass.” State Rep. Darrin Camilleri’s team has knocked on more than 15,000 doors for his re-election campaign this year. None of them have any Biden literature to hand out, because the state Democratic Party hasn’t finished printing it.

These candidates insist that canvassing, when done carefully, can be safe even amid a pandemic. I went door-knocking on Sunday with Camilleri in Gross Ile, Mich., and he had the choreography down: ring the doorbell, tuck his campaign literature into the door handle, take two big steps backwards, and wait 20 seconds. If the voter answers—which they often do, since everyone is home—he waves and shouts to be heard through his mask.

Camilerri, a 28-year old former high school social studies teacher, was first elected to represent a region called downriver in the Michigan House of Representatives in 2016 after personally knocking on 17,000 doors. It’s an area full of the union workers and pocketbook voters that were once gettable for Democrats, but helped elect Trump that year. “Door knocking is the only way, in my opinion, that any Democratic campaign can win” in this area, he says, noting voters in this area “voted for Trump and they voted for me.”

When Camilleri approaches a small house in a neat neighborhood, Mark Ferrera answers the door, takes Camilleri’s mailer, and stops to chat as his dog scratches at the screen door. A retired union autoworker, Ferrera says he’s a lifelong Democrat who voted for Clinton in 2016. Camilleri will get his vote, but Ferrera’s still not sure whether he’ll vote for Biden. “Right now, the way he’s campaigning—I want to hear what he can do, not just bashing Donald Trump,” he says. “I haven’t heard anything from Joe Biden yet.”

These are the conversations that Camilleri says have helped him keep his seat—and which spell trouble for an all-digital campaign. “That’s what I’m worried about going forward, that we’ve got another presidential campaign that is taking votes for granted,” says Camilleri. “They’re using data, and they say, ‘Well, these people should vote for us.’ No one’s gonna vote for you until you ask.”

On Camilleri’s canvassing route, some Democratic voters were still waiting to be contacted by Biden’s campaign. Michelle Kirk, a 46-year old middle-school English teacher, was so excited to see Camilleri canvassing that she ran out of her house in her bare feet. Standing in her driveway without shoes or socks, Kirk said she planned vote for Biden in November. But had she heard anything from his campaign? “I don’t want to say no,” she says. “But not really.” TIME