[ad_1]

After her longtime friend died of COVID-19, Abigail Echo-Hawk sat in her chair crying.

She wondered if her friend and mentor, a Native American like her, would be counted among the deaths – a worry that only added to her grief.

“I couldn’t help this thought that ran through my head: Is his story going to be present in the data? Or did we lose him even there?†she said of the tribal leader in his mid-50s.

Echo-Hawk is chief research officer at the Seattle Indian Health Board and a member of the We Must Count Coalition. The group of health equity leaders calls for better health data tracking to shed light on racial disparities because people of color suffer disproportionate rates of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths as a result of longstanding systemic inequities and racism.

A lack of data is further masking vaccination rollout transparency, health equity researchers say, and the data deficit is hurting those most vulnerable. So far, only 16 states are releasing vaccination counts by race and ethnicity, and the data is incomplete.

ZIP code-level vaccination data also is not widely available, obscuring which residents of specific neighborhoods are getting the shots. Isolated communities, such as rural and low-income pockets of urban cities, are especially vulnerable.

“If you don’t actually disaggregate the data, see where the people are – you will then have people die who should not be dying,†said Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, a doctor and senior adviser to the coalition who founded the National Birth Equity Collaborative.

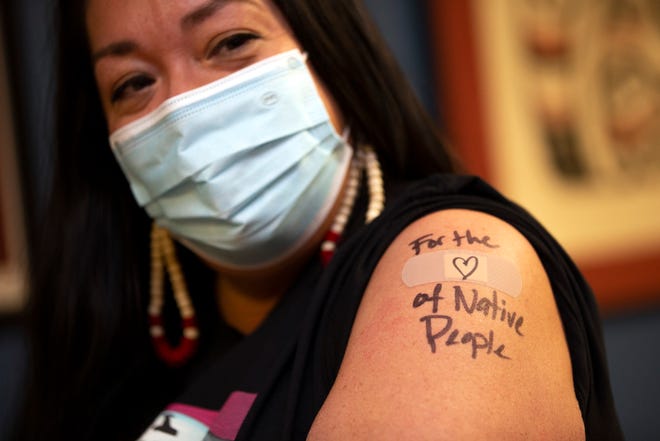

‘Bringing all the facts to the table’:Native American tribes receive COVID-19 vaccines, and health officials work to ease fears about taking it

The preliminary figures from those 16 states are already raising concerns, according to a recent report by the Kaiser Family Foundation. The analysis shows that the share of vaccinations among Black people in those states is smaller than the number of cases among Black people in all 16 of those states, and smaller than their share of deaths in 15 states.

Similarly, Hispanic people accounted for more deaths and cases than vaccinations in most of the states.

Data on American Indians, Alaska Natives and Pacific Islanders is missing.

“We are losing our language speakers. We are losing our elders who carry the stories and the songs,†Echo-Hawk said. “The other place where they’re being lost is the data, because they are not being captured by their race and ethnicity correctly within the data, either when they go into the hospital systems, when they are diagnosed with COVID –and then when they die.â€

‘We cannot improve what we’re not willing to measure’

The Biden administration has created a COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force as part of an ambitious pandemic relief plan that promises an expansion of “equity data collection.â€

In a White House press briefing Monday, task force chair Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith discussed the effect of the lack of data on communities of color and equitable vaccination.

“As of Jan. 30, we’re missing 47% of race and ethnicity data on vaccinations,” Nunez-Smith said. “Let me be clear: We cannot ensure an equitable vaccination program without data to guide us. … But I’m worried about how behind we are. We must address these insufficient data points as an urgent priority.”

Nunez-Smith said several factors are to blame, including uneven rollout among states and “inconsistent emphasis on equity in the early days of vaccination.”

Tracking COVID-19 vaccine distribution by state:Â How many people have been vaccinated in the US?

The We Must Count Coalition wrote letters imploring the Trump and Biden administrations to invest in a public health data infrastructure, pointing to the elusiveness of health data under America’s decentralized health system. “We cannot improve what we’re not willing to measure,†the authors wrote.

State lawmakers includingDemocratic Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey as well as Rep. Ayanna Pressley also recently called on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to collect and release demographic data of vaccine recipients and prioritize hard-hit communities.

“We urge you not to delay collecting this vital information,†the legislators wrote in their letter to Acting HHS Secretary Norris Cochran IV.

Dr. Rebecca Weintraub, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said improving data on vaccinations would help officials better track distribution.

“The data systems that we have now, there’s so little public data,†she said. “In order for equitable distribution, we actually need this level of transparency now. Even if it’s incomplete. It helps us audit, it helps us support those states in a positive way versus reporting they’re not doing X. We want to help states get better, prepare better each week. But it’s difficult to do without access to this data.â€

In a joint editorial published Friday in The Journal of the American Medical Association, two physicians called on systems to ensure health equity in vaccine distribution as hurdles are magnified in communities already lacking health care access and other barriers.

“Communities should be able to generate daily and certainly weekly data to understand the demographics of who is being vaccinated. Local health departments and health institutions need to respond to these data in real time to identify where COVID-19 vaccine uptake is not matching COVID-19 disease burden,” wrote Dr. Muriel Jean-Jacques, Northwestern University Department of Medicine vice chair of diversity, equity and inclusion, and Dr. Howard C. Bauchner of the Boston University School of Medicine, a professor of pediatrics and community health.

“If disparities emerge, then additional targeted approaches to vaccine outreach, education, and administration, for example, house to house contact, may be necessary,” they said.

More:Amid access hurdles, grassroots efforts underway to get COVID-19 vaccine to at-risk people of color

Black Americans are twice as likely as white people and Native Americans more than three times as likely to contract COVID-19. But different methods of how race data are collected in health settings – such as observation upon intake, which might not be accurate, or self-reporting – coupled with a lack of uniform laws for race and ethnicity collection and reporting means those figures could be a gross understatement, Echo-Hawk said.

Race data was only reported from about half of more than 12 million COVID-19 vaccine recipients as of mid-January, a CDC demographics analysis published Monday found. Of those patients, 60% of were white.

“More complete reporting of race and ethnicity data at the provider and jurisdictional levels is critical to ensure rapid detection of and response to potential disparities in COVID-19 vaccination,” the authors wrote.

Another CDC study published in August that found the high prevalence of the virus among American Indians could analyze data only from states that reported race and ethnicity more than 70% of the time. That was only 23 states.

Echoing that study, another on COVID-19 disparities in underrepresented racial and ethnic groups noted that many hot-spot counties were missing data on race for a “significant proportion of cases.â€

People of color have ‘been screaming’ for notice

The underreporting of race and ethnicity data in health systems didn’t start with COVID-19.

For years, public health experts like Echo-Hawk and Crear-Perry have been advocating for better health data infrastructure and mandates. The deficit in essential information has long hampered efforts to correct health disparities.

Crear-Perry’s work at the National Birth Equity Collaborative focuses on policy advocacy, training and research to improve Black maternal and infant health outcomes.

“We’re the worst in the world because we haven’t been counting it,” said Crear-Perry, referring to analyses that rank U.S. maternal care as the worst of any developed country. Just last year, the CDC released the first national data on maternal mortality since 2007.

“Health data disparities are a huge, understudied, massive barrier to the kind of work that we need to be doing to unmask health disparities,” said Debra Furr-Holden, an epidemiologist, C.S. Mott endowed professor of public health at Michigan State University and director of the Flint Center for Health Equity Solutions.

The researcher said reporting race and ethnicity data for vaccine distribution, as well as testing, should be required to ensure disaggregation and accuracy.

“The anecdotes are piling up, and it’s not a pretty picture. We don’t know and we should know. And this is an easy fix. This should be mandated,” she said. The federal government “should attach conditions to any state that takes receipt of the vaccine: You must collect the following data points.”

Survey says:Many people don’t believe systemic racism is a barrier to health

In Seattle, Echo-Hawk remembers the time her own son, after suffering a leg injury, was misclassified by a nurse as “white.” The nurse didn’t know “American Indian” was an option on the chart, she said.Â

“They call us the ‘Asterisk Nation,’ because there would be little asterisks that would say, ‘There’s not enough data in order to present’ or ‘not enough data to be statistically significant,'” Echo-Hawk said.

Furr-Holden said she often feels she’s “standing on a mountain top screaming” about the importance of requiring data collection toward equity.

And she’s not the only researcher who feels that way.

“I’ve been doing this for a lot of years. I feel like I’ve been shouting and screaming to states, to those that collect data, large federal data sets, that we are being excluded in the data, that we’re being racially misclassified,” Echo-Hawk said. “It’s limiting our ability to do good science … the data is what is used for the allocation of resources. How are they doing that when the data doesn’t exist?”

Reach Nada Hassanein at nhassanein@usatoday.com or on Twitter @nhassanein_.

Contributing: Aleszu Bajak, USA TODAY

[ad_2]

Source link