[ad_1]

We hear you. The message to retailers from politicians is that they understand business rates place a disproportionate burden on an industry that was going through wrenching structural change even before the pandemic.

Many of those politicians represent constituencies where the state of high streets, hollowed out by shop closures and bankruptcies, is a defining issue for local voters.

The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated an existing shift to online shopping, pushing chains such as Debenhams and Arcadia into insolvency with the loss of hundreds of stores and tens of thousands of jobs.

“Things have changed since Covid,†said Jerry Schurder, head of business rates at property consultancy Gerald Eve. “There is greater acceptance that business rates are just no longer sustainableâ€.

According to Altus Group, another consultancy, rates were a bigger expense than rent for over 12,000 shops even before the pandemic started.

Although retailers are currently exempt from rates under a year-long holiday, extended by three months in the Budget, ministers also like the £25bn that the levy normally raises each year in England alone — a quarter of it coming from retailers. Like all property-based levies, rates are easy to collect and hard to avoid.

Reducing the burden of rates was a Conservative manifesto pledge in 2019, and finding a way to do so without blowing a hole in tax receipts is the purpose of a Treasury review announced last April and set to present its conclusions in the autumn.

The Treasury has indicated it is willing to go beyond simply tweaking the administrative process. But it has also been clear that any reduction must be made good by alternative sources of tax revenue.

Its preferred option is an online sales tax of around 2 per cent, an idea that sharply divides opinion.

More than a dozen retailers, including Tesco and Waterstones, signed a recent letter calling for an online sales tax to fund a cut in rates.

But other executives and analysts oppose it. “I am not in favour and I don’t really understand the argument for it,†said Stuart Adam of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a think-tank.

He argues that such a tax would be passed on to consumers while the benefit of any reduction in rates would largely be capitalised into rents — benefiting landlords rather than retailers.

Alex Baldock, chief executive of Dixons Carphone, said recently that it would both be difficult to administer and add to the overall tax burden.

Financial Times calculations suggest that Dixons and some other high-street retailers could even end up worse off if an online sales tax were used to offset a reduction in business rates.

Steve Rowe, chief executive of Marks and Spencer, wrote in the FT that such a tax risked stifling “the innovation that the sector’s future depends on†and constraining companies such as his from competing with ecommerce.

Business rates are based on open-market rental values assessed by the Valuation Office Agency, part of HM Revenue & Customs, and Baldock’s preferred method for reducing rates is more frequent revaluations.

The last revaluation was in 2017, based on rents in 2015. Since then, shop rents have fallen sharply while those for the giant warehouses used by Amazon and others have risen.

Revaluing more often would speed up the trend towards shops paying lower rates and sheds paying more.

Lord Simon Wolfson, a Conservative peer and chief executive of fashion chain Next, has argued that a similar result could be achieved by applying a different multiplier to warehouses.

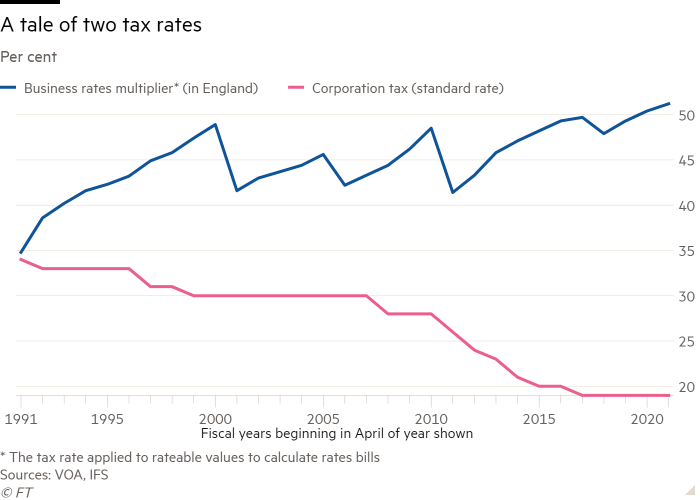

The multiplier is the tax rate applied to all rateable values to calculate rates bills. In England, it has risen from 34.8 per cent in 1990 to 51.2 per cent today.

The Treasury’s consultation also floats this option. Given that the next revaluation is not until 2023, it would be the quickest and simplest way of addressing the perceived imbalance between rates paid by store-based retailers compared with their online-only counterparts. It would also maintain the advantages of property-based taxation.

But it would remove the consistency inherent in the current system and open the door to continuous lobbying by industries arguing that they should pay a lower rate.

Many retailers believe the long-term solution is broader reform of corporate taxation. Rowe advocates a “modest†increase in the UK’s corporation tax rate — currently 19 per cent — to offset a cut in the multiplier to 35 per cent.

But others have privately expressed the view that while the standard corporation tax rate is set to rise to 25 per cent in 2023, it is unrealistic to expect the extra revenue to be applied to reducing business rates when national debt has reached levels rarely seen outside world wars.

A final option is to replace business rates with a land or capital value tax, payable by the owner of the property rather than the tenant. Adam said that in the long term this would be fairer, more efficient and provide more economic incentive to redevelop property for other uses.

Whatever the revenue-raising alternatives, there are two other measures beyond lower multipliers and more frequent revaluations that could reduce the burden of business rates.

One is to end so-called transitional relief. This mechanism aims to smooth the pain of large increases in rates bills, but because, by law, business rates must be revenue-neutral, cushioning rises for some is paid for by limiting declines for others.

Altus Group, a consultancy, highlights a Poundland store in Blackpool that saw its rateable value fall by 46 per cent at the last revaluation in 2017. Its total rates bill over the following three tax years should have dropped to £175,644 — but transitional relief meant it actually paid more than £300,000.

The other measure would be to abandon the requirement for revaluations to be fiscally neutral. At present, any fall in total rateable value is offset by a corresponding rise in the multiplier.

This ensures that government receipts remain constant, but means many businesses see less pass-through from falling rents.

[ad_2]

Source link