[ad_1]

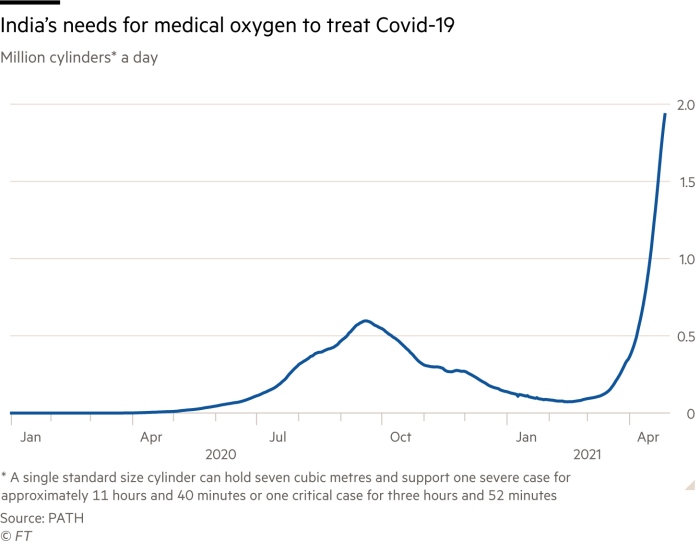

India is in the throes of one of its darkest moments since independence as a catastrophic second Covid-19 wave tears through it with dizzying speed.

The country recorded an all-time high of more than 386,000 new infections on Thursday, along with more than 3,500 deaths. Most experts say the actual number of fatalities is far higher.

Prime minister Narendra Modi and his government have been accused of exacerbating the crisis by failing to prepare after a sharp drop in cases led to claims the country was in the “endgame†of the pandemic.

The latest surge has surpassed anything endured since Covid-19 first struck. It has cut across the country’s many social, economic and geographic divides, affecting both rich and poor in rural and urban areas.

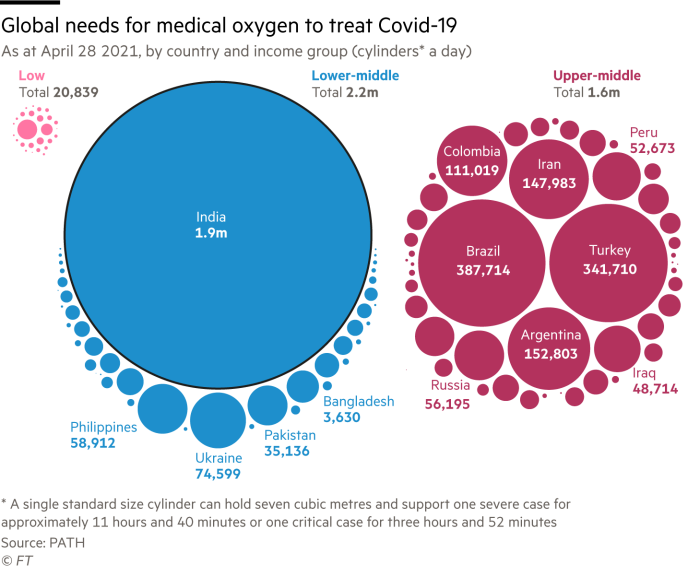

The turmoil has been intensified by a crippling shortage of life-saving supplies such as oxygen as well as new Covid-19 variants. New lockdowns are also threatening to derail the recovery of what had been the world’s fastest-growing large economy.

Here are the stories of four people confronting the crisis.

Aparna Hegde, doctor in Mumbai

During the first wave last year, Aparna Hegde’s ward at the government-run Cama hospital for women and children had about 60 patients at a time. As India’s second wave surged, the number of patients shot up to 100.

She said the strain on hospitals had exposed a lack of preparation and chronic neglect of public healthcare. India spends only about 1 per cent of gross domestic product on the sector.

“We don’t learn from our mistakes at all,†she said. “The first wave ended and we didn’t think that a second wave could come.â€

Circumstances are so dire that Hegde was unable to secure a hospital bed and oxygen for a younger colleague with no comorbidities in Delhi in time to save him. “That young man should not have died,†she said.

Hegde, who runs Armman, a non-profit organisation that works with mothers and children, said the strain was affecting other spheres of public health, with potentially long-term consequences. Child immunisation campaigns had been derailed and pregnant mothers were struggling to receive treatment, she added.

“India doesn’t have to be like this. That’s the thing that’s heartbreaking,†she said. “That’s why it hurts that much more.â€

Vishwanath Chaudhary, chief cremator in VaranasiÂ

The ancient city of Varanasi, on the banks of the sacred Ganges river, is where many Hindus wish to be cremated, which they believe allows their soul to complete its journey to heaven and be released from the cycle of birth and death.

But the flow of bodies to Hindu crematoriums, as well as Muslim or Christian cemeteries, is relentless.

Vishwanath Chaudhary, 39, is the raja, or king, of the Dom caste, which has for generations worked at Varanasi’s cremation grounds.

With the number of bodies arriving daily rising to 100 — compared with as few as 15 last year — the searing heat and leaping flames have become unbearable.Â

“Our family has been traditionally involved in managing the crematoriums for generations. No one has ever seen anything like this,†Chaudhary said.

“[Last year] was nothing like what we are witnessing this time. The situation is horrific,†he added. “At such times humanity is often lost.â€

So dire is the onslaught that it has sparked shortages of wood for the pyres, with vendors raising prices significantly.

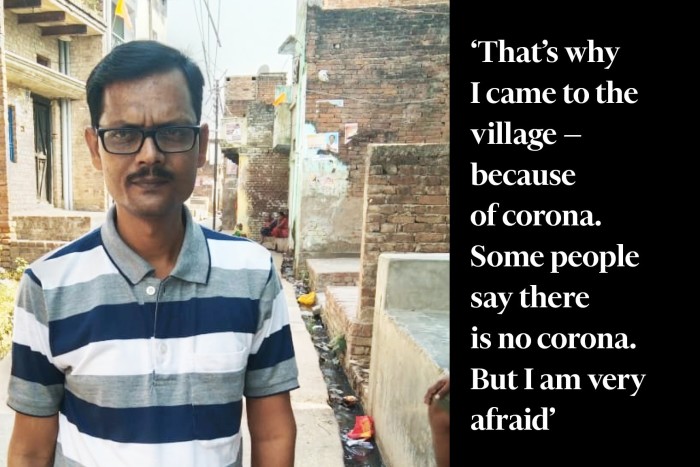

Ram Vilas Gupta, migrant worker in Chandauli, Uttar Pradesh

More than 15 years ago, Ram Vilas Gupta left his family and village in India’s vast hinterland for the metropolis of Mumbai, where he drove a taxi and lived five to a room.

Like millions of other migrants, the 45-year-old was forced into an epic, desperate journey home last year after the country entered a nationwide lockdown and his savings ran out.Â

With India’s caseload falling sharply towards the end of last year — and the economy expected to roar back — he returned to Mumbai and was soon bringing in his pre-Covid monthly earnings of up to Rs18,000 ($243).

However, the recovery did not last. By late March, with Mumbai hard hit by a second Covid-19 wave, his taxi customers stopped coming and his earnings dried up.

Now back in his village and jobless once again, Gupta does not know how he will repay the Rs40,000 of debt he took out during last year’s crisis. “What to do?†he said. “All my savings [are gone]. We had a very difficult time.â€

His biggest fear now is that the virus, which is tearing through rural India, will arrive in his village, where many still doubt it even exists.

“That’s why I came to the village — because of corona. Some people say there is no corona. But I am very afraid.â€

Sourindra Bhattacharjee, university professor in Delhi

Like so many others in recent weeks, 57-year-old Sourindra Bhattacharjee tried and failed to find a hospital bed for his loved one.

India’s middle and upper-classes typically enjoy access to world-class healthcare, even as the poor depend on underfunded government hospitals.

But now, even those who can afford it are struggling to secure treatment.

After the blood oxygen levels of Bhattacharjee’s diabetic elder sister, Gouri, dropped below 80 per cent, the business professor consulted with doctors who advised him to get her hospitalised. A healthy blood oxygen reading is above 90 per cent.

But with beds at hospitals in Delhi full, his two attempts to get treatment for his sister failed. At one emergency room he was turned away by a doctor who pointed to a young man with oxygen levels as low as 13 per cent. “Look at his reading,†the doctor told him. “Now tell me, who should we choose?â€

“I realised there was no point trying,†Bhattacharjee said. “I brought her home.†He found an oxygen cylinder for his sister, but he did not have the equipment needed to hook her on to it.

His sister is still at home with him while he tries to ensure she recovers — and not become infected himself. “She seems to be on the mend,†Bhattacharjee said. “God has been kind to me.â€

Additional reporting by Harry Dempsey in London

[ad_2]

Source link